|

| articles | forbidden stories I-State Lines resources my hidden history reviews | home | ||

Writing/Film Dear Aspiring Writers: The Worst Advice You'll Ever Read A Literary Look at I-State Lines Spirited Away: Decay and Renewal An American Poem (Robinson Jeffers) Taoist Chinese Poems The Nelson Touch "It's all about oil, isn't it?" Kurosawa's High and Low A Bountiful Mutiny Howl's Moving Castle Thailand's Iron Ladies Trois Colours: Red The Thin Man: Thoroughly Modern Movies Why My Book Is Better Than the DaVinci Code Iranian Films: The Mirror Piratical Nonsense A Real Pirate Movie: Captain Blood 9 more in archive Recommended Books American Identity American Identity Literary Contest Winners, 2006 (fiction and essays) Hapas: The New America Can You Tell What I am? Part I Can You Tell What I am? Part II Only in America Self-Reliance Your Tattoo in 50 Years The American House and Frank Lloyd Wright Cultural Commentaries On Hatred and Anti-Americanism Anti-Americanism Part 2 Anti-Americanism Part 3 French-Bashing Germany: We All Have Problems, But... Kroika! Chronicles This Blog Sells Out Doom and Gloom Sells The Kroika Mascot-"Auspicious Pet" Wal-Mart and Kroika Kroika and Starsbuck Take a Hit Kroika Ad 1 Kroika Ad 2 Kroika Ad 3 Kroika Ad 4 Kroika Makes Bid for Oreo (April 1) Unfolding Crises: Asia China: An Interim Report Shanghai Postcard 2004 Corruption and Avian Flu: China's Dynamic Duo Exporting the Real Estate Bubble to China Is the Bloom Off the China Rose? China Irony: Steel, Marx & Capital Curing The U.S. and China's Dysfunctional Relationship China and U.S. Inflation Trade with China: Making Out Like a Bandit Whither China? Will the Housing Bust Take Down China? China's Dependence on Exports to U.S.; Is China About to Pop? 8 more Battle for the Soul of America Katrina, Vietnam, Iraq: National Purpose, National Sacrifice Is This a Nation at War? A Nation in Denial Why Is This Such a Tepid Time? That Price Isn't Cheap, It's Subsidized The Most Hated Company in America U.S. Fascists Seek Ban on Cancer Vaccine The Truth About Christmas American Dream or American Nightmare? 2006 Sea Change Obesity and Debt Immigration Ironies U.S. Healthcare: Working Toward a Real Solution A Drug Industry Running Amok Where There Is Ruin 10 more Financial Meltdown Watch What This Country Needs Is a... Good Recession Are We Entering the Next Age of Turmoil? Why Inflation Appears Low Doubling Down on 5-Card No-See-Um A Rickety Global House of Cards Are Japan and Germany Truly on the Mend? Unprecedented Risk 2 Could One Rogue Trader Bring Down the Market? Worried about Inflation? Stop Measuring It Economy Great? Bah, Humbug Huge Deficits and Huge Profits: Coincidence? Who's The Largest Exporter? Three Snapshots of the U.S. Economy Loaded for Bear Comparing Nasdaq to Depression-Era Dow Who's Buying Treasury Bonds? And Why? Derivatives: Wall Street Fiddles, Rome Smolders Financial Chickens Coming Home to Roost Is the Stock Market on the Same Planet as the Economy? The Housing-Recession-Oil-Healthcare Connection Could We Have Deflation and Inflation At the Same Time? What We Know, What We Can Safely Predict Bankruptcy U.S.A.: Medicare, Greed and Collapse Sucker's Rally A Whiff of Apocalypse Where There Is Ruin II: Social Security 31 more Planetary Meltdown Watch The Immensity of Global Warming Sun Sets on Skeptics of Global Warming Housing Bubble Watch Charting Unaffordability A Monster of a Housing Bubble A Coup de Grace to the Economy Hidden Costs of the Housing Bubble Housing Bubble? What Bubble? Housing Bubble II Housing Bubble III: Pop! Housing Market Slips Toward Cliff Housing Market Demographics Housing: Catching the Falling Knife Five Stages of the Housing Bubble Derailing the Property Tax Gravy Train Bubbling Property Taxes Have You Checked Your Property Taxes Recently? Housing Bubble: Where's the Bottom? Housing Bubble: Bottom II The Housing - Inflation Connection The Coming Foreclosure Nightmare 1 How Many Foreclosures Will Hit the Market? Housing Wealth Effect Shifts Into Reverse Housing Bubble Bust Will Take Down the Global Economy The New Road to Serfdom: A Negative-Equity Mortgage The Housing-Savings-Recession Connection After the Bubble: How Low Will It Go? After the Bubble: Rents and Housing Values Why Post-Bubble Rents Matter After the Bubble: How Low Will We Go, Part II Housing: 10% Decline May Trigger Financial Ruin How to Buy a $450K Home for $750K Inflation and Housing: Calculating the Bust The Growing Financial Risks of the Housing Bubble Construction Defects: The Flood to Come? Construction Defects Part II Who Gets Hammered in the 2007 Housing Bust Real Estate Bust: The Exhaustion of Debt What Happens When Housing Employment Plummets? One More Hole in the Housing Bubble: Insurance Financial Kryptonite in a "Super-Strength" Housing Market Three Secrets to Unloading Property Today Welcome to Fantasyland: Housing's "Soft Landing" Why Is the Median House Price Still Rising? Why Median Prices Appear to be Rising? The Root Cause of the Housing Bubble Housing Dominoes Fall Twilight for Exurbia? Phase Transitions, Symmetry and Post-Bubble Declines Housing's Stairstep Descent 10 more Oil/Energy Crises Whither Oil? How much Is a Gallon of Gas Worth? The End of Cheap Oil Natural Gas, Naturally High Arab Oil Money and U.S. Treasuries: Quid Pro Quo? The C.I.A., Oil and the Wisdom of Crowds The Flutter of a Butterfly's Wings? A One-Two Punch to a Glass Jaw Running Out Of Oil vs. Running Out of Cheap Oil 2 more Outside the Box How to Make a Favicon Asian Emoticons In Memoriam: Winky Cosmos The Wheeled Vagabonds Geezer Rock Overload Paying for Web Content Light-As-Air Pancake Recipe In a Humorous Vein If Only Writers Had Uniforms Opening the Kimono Happiness for Sale: Jank Coffee Ten Guaranteed Predictions for 2010 Why My Book Is Better Than the DaVinci Code My Brand Management Stinks Design Follies The New Jank Coffee Shop Jank Coffee, Upscale Tropic Style One-Word Titles Complacency Nostalgia Lifespans Praxis Keys to Affordable Housing U.S. Conservation & China Steve Toma, Me & Skil 77s: 30 years of Labor Real Science in the Bolivian Forest Deforestation and Sustainable Forestry The Solar Economy (book) The Problem with Techno-Fixes I Love Technology, I Hate Technology How To Blow off Web Ads and More 2 more Health, Wealth & Demographics Beauty of the Augmented (Korean) Kind Demographics and War The Healthiest Cold Cereal: Surprise! 900 Miles to the Gallon Are Our Cities Making Us Fat? One Serving of Deception Is Obesity an Inflammatory Response? Demographics & National Bankruptcy The Decline of Europe: A Demographic Done Deal? Are the Risks of Obesity Overstated? Healthcare: Unaffordable Everywhere Medication Nation The New Disease We Just Know You've Got Can You Can Tell Which Pill Is Fake? Bankruptcy U.S.A.: Medicare, Greed and Collapse The 10 Secrets to Permanent Weight Loss 5 more Landscapes Selling the Landscape The Downside of Density Building Heights and Arboral Roots Terroir: France & California L.A.: It's About Cheap Oil The Last Redwood Airport Walkabouts Waimea Canyon, Yosemite, Camping & Pancakes Nourishment The French Village Bakery Ideas What Is Happiness? Our Education System: a Factory Metaphor? Understanding Globalization: Braudel Can You Create Creativity? Do Average People Know More Than Their Leaders? On The Impermanence of Work Flattening the Knowledge Curve: The "Googling" Effect Human Bandwidth and Knowledge Iraqi Guangxi Splogs, Blogs and "News" "There is no alternative to being yourself" Is There a Cycle to War? Leisure, Time and Valentines Is the Web a Giant Copy Machine? Science Matters Anti-Missile Defense: Boost Phase Vulnerability History The Strolling Bones: Rock of Ages Bad Karma: Election Fraud 1960 Hiroshima: First Use All the Tea in China, All the Ginseng in America Friday Quiz Pet Obesity The Origins of Carbonara Organic Farms Oil and Renewable Energy Human Diseases Wine and Alzheimers Biggest Consumers of Chocolate 7 more Essential Books The Misbehavior of Markets Boiling Point (Global Warming) Our Stolen Future: How We Are Threatening Our Fertility, Intelligence and Survival How We Know What Isn't So Fewer: How the New Demography of Depopulation Will Shape Our Future The Coming Generational Storm: What You Need to Know about America's Economic Future The Third Chimpanzee: The Evolution and Future of the Human Animal The Future of Life Beyond Oil: The View from Hubbert's Peak The Party's Over: Oil, War and the Fate of Industrial Societies The Solar Economy: Renewable Energy for a Sustainable Global Future The Dollar Crisis: Causes, Consequences, Cures Running On Empty: How The Democratic and Republican Parties Are Bankrupting Our Future and What Americans Can Do About It Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy Revised and Updated Recommended Books More book reviews Archives: weblog December 2006 weblog November 2006 weblog October 2006 weblog September 2006 weblog August 2006 weblog July 2006 weblog June 2006 weblog May 2006 weblog April 2006 weblog March 2006 weblog February 2006 weblog January 2006 weblog December 2005 weblog November 2005 weblog October 2005 weblog September 2005 weblog August 2005 weblog July 2005 weblog June 2005 weblog May 2005 What's New, 2/03 - 5/05

|

|

January 31, 2007 Brittleness and Risk, or, Hedge Funds As Rats  Another way to think about brittleness and resiliency is to look at risk. A classic

example is forest fires. In the normal cycle of events, dry underbrush and other material

accumulates on the forest floor, becoming the fuel for a fire which burns the dried leaves and branches,

fertilizing the soil with the ashes and setting the stage for regrowth.

Another way to think about brittleness and resiliency is to look at risk. A classic

example is forest fires. In the normal cycle of events, dry underbrush and other material

accumulates on the forest floor, becoming the fuel for a fire which burns the dried leaves and branches,

fertilizing the soil with the ashes and setting the stage for regrowth.

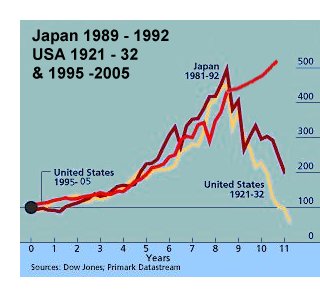

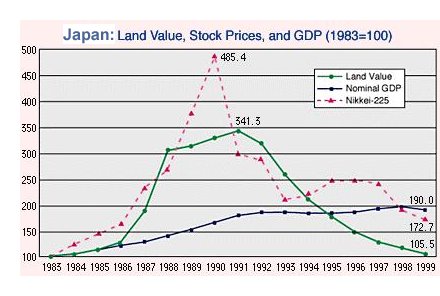

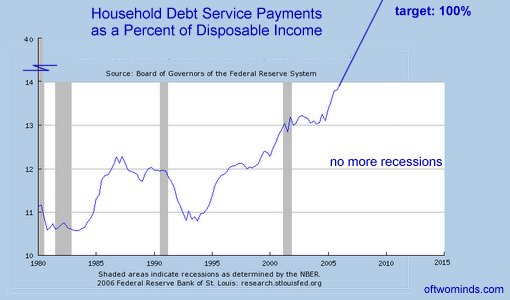

Every so often, various conditions lead to a period without smaller fires, building up enough fuel for a large conflagration. These larger events tend to obey what's known as a power law: the more infrequent they are, the larger they are (and vice versa). Here is an explanation by Jim Sloman: In fact, they found that the size of earthquakes followed a law known to mathematicians as a power law. This law, now known as the Gutenberg-Richter Law, states that when you double the energy of an earthquake it happens four times less frequently.So what happens when authorities stamp out all small forest fires? They create the perfect conditions for a gigantic conflagration. The flaw is the old forest management policy of suppressing all forest fires was revealed when a huge uncontrollable fire swept through Yellowstone National Park some years ago. In other words: a system which allows occasional fires is resilient, while one which suppresses all small fires guarantees a giant conflagration. In financial terms, this "normal cycle" of growth, small fires and regrowth is "the business cycle" in which credit and business expand, eventually reaching an unsustainable level (high inventories, too much debt and capacity, etc.) Businesses go bankrupt, defaulting on credit, people save rather than borrow, and capital is accumulated for the next cycle of investment and borrowing.  Consider the above chart of the Nasdaq dot-com era bubble. Fed Chairman Greenspan

famously warned that there seemed to be an awful lot of dry underbrush accumulating

in the stock market back in 1996, but the nervous swoon which greeted his observation

soon passed, and the glorious euphoria of "free market forces at work" resumed, leading to

a peak of over 5,000 in March 2000.

Consider the above chart of the Nasdaq dot-com era bubble. Fed Chairman Greenspan

famously warned that there seemed to be an awful lot of dry underbrush accumulating

in the stock market back in 1996, but the nervous swoon which greeted his observation

soon passed, and the glorious euphoria of "free market forces at work" resumed, leading to

a peak of over 5,000 in March 2000.

How many analysts and pundits recognized the tremendous risk at the height of the bubble? Very few. Various Cassandras had been warning of rising risk for years, but their paltry investment returns only seemed to prove they didn't know what they were talking about. But like a rubber band being stretched ever farther--or a forest accumulating dry brush for years on end--an "event" was inevitable. Here we have a chart of housing prices in California. Hmm. Anyone else see an accumulation of dry tinder awaiting a lightning strike? There is another analogy for this notion of risk: a grain ship over-run with rats. Let's say there are virtually no controls on the population of the rats, and as a result they proliferate at an astonishing rate, engorging themselves on the seemingly limitless supply of grain. Alas, as the population explodes, the competition for the remaining grain increases. As the winners consume the last of the grain, the entire ship's population is doomed to starvation. A once-stable population explodes beyond its means, and then collapses. Hmm. Now let's substitute hedge funds for the rats, liquidity for grain, and competition for "alpha" (gains in excess of the broad market). Scroll back down to Monday's entry and take a look at the rise in derivatives. Does it remind you of Nasdaq's final rise? Perhaps it should. And what happened to Nasdaq in the 2.5 years following the peak? Collapse. Just to extend the analogy: there are only about 10,000 tradable stocks in the investment universe, and it's estimated there are 9,000+ hedge funds--the exact number is unknown due to lax oversight. One hedge fund for every public company. Does anyone else think the rats are approaching the last bags of grain? January 30, 2007 Vulnerability, or, Thinking About the Unthinkable The President of Iran has made no secret of his desire to destroy Israel, a small nation which zealots gloatingly describe as a "one-bomb state," meaning that one nuclear bomb would wipe the country from the map. But perhaps the Iranian zealots should take a close look at a map of their own nation before they gloat too much. For one glance reveals that theirs is about a "ten-bomb state" facing an opponent (Israel) with an estimated 25 to 50 nuclear-armed missiles.

As we discussed yesterday, systems in which key components or assets are highly concentrated are inherently brittle, or vulnerable. As we peer into the dark globe that is nuclear war, we should recall that many people thought very deeply about the issues of vulnerability, targeting and survivability during the Cold War between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. For starters, I would recommend a classic of that literature, Thinking about the Unthinkable Though it is widely assumed a nuclear war means the end of a nation, even one as large as the U.S., it is not strictly true. The level of destruction depends of course on the number of weapons deployed, but it is heavily dependent on the diffusion /concentration of a nation's assets. A comparison of the U.S. and U.S.S.R.'s brittleness and resiliency--a comparison of the concentration and therefore vulnerability of key assets--reveals that the Soviet Union was far more vulnerable to a nuclear attack than the U.S. for the simple reason that the majority of its human and physical capital are centered in Moscow. With few ports and rail centers, and much of its energy and military complex in tight concentrations, a "limited strike" of perhaps 100 weapons would have destroyed virtually the entire core of Soviet power while leaving most of its people unaffected. The political, transportation, energy, military and human capital of the U.S. is more widely distributed, and so even though a 100-weapon strike would have devastating consequences, to say that the U.S. would be utterly destroyed would simply not be true. There would be roads, railways, ports, energy assets, intellectual capital, and political structures which would survive a 100-bomb strike. Now I want to stress here that I am not underplaying the effects of nuclear weapons, or advocating their use. I am simply pointing out that states in which the capital city contains the vast majority of the nation's political and intellectual capital, as well as much of the industry, expertise, transportation and energy facilities, are far more vulnerable to nuclear attack than nations with widely dispersed assets. Even a cursory look at Iran reveals that the majority of that nation's human and physical capital is in Tehran, and much of the nation's primary asset--oil--is concentrated in a handful of fields and transported in a handful of pipelines. Most of the country is a desert wasteland; once its capital were leveled and its oil facilities destroyed with ground-burst nuclear weapons, there would be few resources or assets left to work with. My point is simply that a "ten-bomb state" with highly concentrated assets had better be careful toying with a "one-bomb state" with 25-50 deliverable warheads. The Israels would, after the first 20 or so weapons, be reduced to hitting secondary targets or "bouncing the rubble" in Tehran. There are also various levels of brittleness and vulnerability in weapons delivery systems. If your missiles are above ground or in visible (and therefore targetable) hardened silos, and you have a habit of boasting about your desire to deliver a nuke on said missiles, your enemy may decide to pre-emptively destroy your missiles with an air-burst nuclear weapon, frying its electronics, guidance and command-and-control systems, or destroying the silos with ground-burst nukes. The Israelis are also proported to maintain an undersea-launched (i.e. from a submarine) missile capability, one which is very hard to pre-emptively destroy. Which has the more resilient system? The "one-bomb state" with submarine-launched nuclear tipped missiles, or the "ten-bomb state" with vulnerable surface missiles? Just for comparison's sake: The U.S. maintains 18 "boomers" (Ohio-Class Fleet Ballistic Missile Submarines--SSBNs), each armed with 24 D-5 Trident missiles, which are each armed with 5 independently targetable warheads (MIRVs). Each U.S. SSBN thus carries 120 nuclear warheads, launched within one minute and deliverable anywhere in the world. That's 2,160 nuclear warheads distributed among 18 very-hard-to-locate boats. Not all are at sea at any one time, but catching a few in dock would still leave 1,500 or so nuclear weapons available for a counter-stike. What nation would chance absorbing even one SSBN's load of 120 nuclear bombs? That is resilence, which in the parlance of nuclear war translates to deterrence. It's a word which should be in everyone's vocabulary--even those ruling a "ten-bomb state." (Note: to comply with the Start II nuclear weapons reductions agreement with Russia, the U.S. will reduce its fleet of Ohio-class submarines from 18 to 14 in a few years.) But nuclear deterrence is not robust in all circumstances. As we have learned, it has little value against stateless terrorism--or even the state-sponsored variety. Just as a thought experiment: what if an anonymous nuclear bomb were to be trucked into the heart of Tehran and detonated? Yes, there are "signatures" to weapons--how "cleanly" they exploded--but what if a "clean" weapon were modified to be "dirty" enough to look amateurish? Then who would the President of Iran--were he still among the living--attack? The deterrence of nuclear bombs doesn't erase the threat of nuclear terrorism, it would seem, even for those states which sponsor conventional terrorism. January 29, 2007 Brittleness Some time ago our U.K. Correspondent sent in some comments on the "brittleness" and resilience of systems--such as economies. This is a "systems analysis" view of complex systems, and as such it can be profitably applied to everything from the immune system to the electrical grid to the stock market. Here is his brief commentary: (emphasis added) Moving the analogy to economics I would ask: Is it better to have an economy that degrades and rebounds gracefully under stress or one that bears heavy loads but which fails dramatically when it hits the limits? The first is inherently robust but exhibits many variations in state. The second shows much more stability - but offers fewer indicators of the stresses the system is under.  Though I am still learning about such analytic tools, it seems that many of the complex

systems we rely on are also extremely brittle in the sense that they depend on a handful

of chokepoints.

Though I am still learning about such analytic tools, it seems that many of the complex

systems we rely on are also extremely brittle in the sense that they depend on a handful

of chokepoints.

And so on. The idea behind hubs and ports and highly consolidated industries (there are only two manufacturers of large commercial aircraft in the entire world, for instance) is that the resulting economy of scale will be efficient. But as our U.K. Correspondent points out, that consolidation carries a cost which is only visible when the brittleness of such concentration becomes glaringly apparent. To take another disturbing example: bird flu (H5N1) has killed 150 million birds globally. This virus somehow overcomes birds' normally robust immune system. Research suggests that the global Flu Pandemic of 1918 which killed millions of humans was a bird virus which "jumped" to human hosts. The immune response to that virus caused massive congestion in the lungs, causing the human host to suffocate. In effect, the normally resilent human immune system was rendered brittle by this terrible microbe. The global financial markets, we are constantly reassured, are actually made more resilient by the instantaneous flow of capital across borders and by the proliferation of derivatives. But what if the opposite is true, and the global financial markets have been pushed by an unprecedented tide of derivatives to the edge of chaos? More on that later. January 27, 2007 Portrait of the Artist II Thank you to everyone who responded to yesterday's entry and/or wished me well with my new novel: Bill M., Michael G., Albert T., Kevin M., our U.K. Correspondent, et. al. I think Kevin put into words what many of us feel: While reading your blog today, I was struck by a way of thinking and living that I have subscribed to (or tried to anyway). I am tired of being a "consumer / producer," and as such I no longer worry about anything creative that I do as having any commercial value. I simply enjoying creating things. I too play my guitar 30 minutes to an hour a day. I enjoy working on my motorcycle. Even mowing my yard. The end result and the process itself is my reward, and I don't worry too much about what other people think.There's a lot of wisdom in those words.... Several readers requested Richard Russell's views on Chelation therapy, and correspondent James C. was kind enough to send me a copy. It is currently in Microsoft Works format, which should open in most Windows PCs. If you have a Mac, try downloading the file and then opening it in a Mac word processor. I will transfer it to HTML when I have time: Russell on EDTA Chelation. I should note here that I am not recommending this or any other treatment. What I am recommending is doing your own research, and maintaining both an open mind and a skeptical mind. No one treatment or lifestyle works for everyone; learn as much as you can, and take charge of your own health. Here are some interesting links for weekend browsing. Polymath reader Bill M.'s own website is a delightful mix of eclectica (is that a real word?), including a large-batch recipe for thin pizza crust dough and some stunning craftwork: amulets and chimes. Frequent contributor U. Doran sent in some links to stories you may have missed. Everyone talks about hedge funds, but how much research about this shadowy industry have you read? Here's a Deloitte Reserach Group report: Risk Management and Valuation Practices in the Global Hedge Fund Industry. Doran also sent in a report on the dollar and bonds (lots of good charts) and another important one which explains how the "new" CRB (Commodities Research Bureau) index has changed dramatically from the "old" CRB index.  Lastly, several readers have been asking for recent entries and noting that they're not in

my archives. That's because I've fallen way behind and need to devote some time to updating

the archives. I am also starting a new archive for 2007 which will include the date of

each entry. Given the hundreds of stories and entries cluttering up this site, I need to

start a new archive lest the existing one become too cumbersome to use.

Lastly, several readers have been asking for recent entries and noting that they're not in

my archives. That's because I've fallen way behind and need to devote some time to updating

the archives. I am also starting a new archive for 2007 which will include the date of

each entry. Given the hundreds of stories and entries cluttering up this site, I need to

start a new archive lest the existing one become too cumbersome to use.

As for the photo: what could be more all-American than a rock-n-roll jam with the flag and a classic Fender Stratocaster? OK, I should be playing slide with an empty bottle of American beer rather than a Beck's, and I am sure there were some Sierra Nevada bottles awaiting the next break. If you haven't heard my songwriter buddy Mike Dakota's tune King George is Back, check it out (it's an MP3 file). That's me on first lead guitar (not very good but it at least it doesn't ruin the song). Another excuse to thank you readers: at some point this week, the 500,000th visitor since 1/1/06 will view this site (and hopefully won't leave in a huff). January 26, 2007 Portrait of the Artist as... Scullery Maid  While I was scrubbing the bathroom floor yesterday, my mind wandered to the film

American Splendor

While I was scrubbing the bathroom floor yesterday, my mind wandered to the film

American SplendorIt's the story of what you might charitably describe as an eccentric (or misanthrope, if you prefer) who is driven to create comic book dialogs. Since he can't draw worth beans, he illustrates his stories with childish stick figures. But by happenstance he knows comic book artist (and fellow eccentric) R. Crumb, who likes the stories and goes on to illustrate many of them. ("Six Degrees" note: my brother's office in the south of France is located a stone's throw from R. Crumb's home in a small, terribly picturesque old village.) Gary's point about artists (meaning any creator, not just a painter-type) is that the real ones have to create what they create--it is not willed or even stoppable. The character in American Splendor is just such a person--he doesn't calculate the probable success of his art/creations, or model them on others' templates--he just does what comes to him. He literally cannot stop himself from putting his ideas to paper. We know this Portrait of the Artist as Slightly Mad Godlike Creator from various movies, and of course the guy/gal is always eventually recognized as a genius. But there are many more creative types (like me, for instance) who never achieve any recognition. Hence, Portrait of the Artist as Scullery Maid. Maybe our work is mediocre, or not of our own era, or maybe it's just too bizarre to ever resonate with enough people to achieve recognition/popularity. The artist has no idea why he/she is scrubbing floors rather than being toasted by the glittering critical elite. This is not a complaint, just a reality. You may wonder why I tossed in a photo of myself playing my 1976 Les Paul Deluxe. I did this mostly because I was tired of text-only entries, and wanted some color, but the other reason is to illustrate the point: I am a mediocre musician, but I have fun improvising and learning (slowly) new material. When I'm feeling good, I often play for a half-hour or more a day (usually acoustic, to keep my fingers strong). When I'm down, I don't play. Creating something, even a melody no one else will hear, is its own reward. Ditto a nice meal, a sketch, a poem, or any other creation. The glory of art is a false attractor. As a writer, I have struggled with this question: am I really driven to put down this story running in my head, or am I merely hoping to win recognition? After two decades of very limited success, it's clear that I am doing it for the internal rewards of creation. The external rewards have been limited and are very likely to remain so. (My first novel was a commercial bomb, selling only a couple hundred copies last year. This is, my publisher reports, pretty typical--but still, disheartening to the hopeful artist.) As for free-lancing--the average free-lance writer makes less than $5,000 a year. Hoo-hah. The illusory nature of artistic success is brilliantly illustrated by the 1960 film The World of Apu, I just finished a 160,000 word novel and shipped it to my publisher. Only God knows if they will like it and publish it, or if it will languish for the rest of my life on a dusty shelf, waiting patiently to be tossed in the recycling bin when I croak off. Either scenario is possible, with the odds favoring the latter. This is the deal with creating: you can't know there will be a market for your ideas or work. The odds are there won't be. the only thing the artist can know is: that melody sounds good, this sentence sounds right, that stroke of color works. Important correction: Yesterday's entry stated that government employees have no stake in Social Security. As knowledgeable reader Nikki reports, that is no longer true: This is only true for federal employees under the Civil Service Retirement System (CSRS). That ended in 1998, and all Fed employees hired since then, like me, do indeed have to pay into SS under FERS, or the Federal Employee Retirement System. I've got SS taxes taken out of every check, and I'm convinced I'll never see a dime. But be assured that some fed workers do worry about social security.Thank you, Nikki, for this clarification. January 25, 2007 Readers Weigh In Taxes, entitlements and military spending have generated a wide variety of interesting commentary. Herewith is a selection (slightly edited for length) of reader feedback. Strawgold makes an excellent point about government employees' retirement plans and Social Security: I read your column about Social Security and “who gets hurt” if it goes under. But here’s what makes even more interesting reading: GOVERNMENT WORKERS DON’T HAVE TO WORRY ABOUT Social Security GOING UNDER. They are not covered under it like the rest of us ( yes, us - the ones who are paying for everything) are. THEIR retirement plan, through the good old Federal Govt has our meager Social Security beat all to the devil and is in no danger of being phased out, or going broke in the same way.Those familiar with the philosopher John Rawls will find resonance in David M.'s observations on morality and taxation: I again have had to suppress my disbelief at the world when reading your reader’s comments in your latest blog posting. His assertions that he has a “right” to all his earnings have at least two main problems: he has undoubtedly benefited from a peaceful society, education, and transportation; and society as a whole is likely to suffer from his expenditures (pollution, scarcity of resources).Frequent contributor Michael Goodfellow comments on the correlation between low tax-rate nations and high GDP, and on my DoD spending entry: I also wondered what would happen if you listed those same countries in your international comparison sorted by GDP per person. I'm pretty sure the U.S. and Japan would be number 1 and 2, just as they are last in taxes on your graph. Not sure the correlation would hold up, but it still should make you think.Another astute reader (Michael) was kind enough to send in a link on Affluenza and the consequences of our cultural obsession with material wealth: Earn more, spend more, want moreNext up is David A., who comments on the unsustainability of the Social Security model, and on governmental waste: Charles, all this vastly huge Medicaid/Medicare and social security spending is in the future so THAT DEBT DOESNT COUNT!!! future debt isn't important as we will be able to pay for it in some miraculous, painless way!Frequent contributor Harun I. notes that morality isn't the only metric for taxation, nor is the cost of maintaining a military the only consideration--losing is expensive, too: I didn’t take your view about taxation from a moral standpoint but from a correlative perspective. I also take issue with some of your readers linear thinking in regards to complex non-linear social issues. There may not be a moral basis for taxes to support social welfare but what will we do when the poor and disaffected are rising up in revolt. I have no answers, I merely raise the question of whether morality is the only benchmark by which social policy is formed. The poorest members of any society will burden that society to some extent and possibly in ways that are very undesirable.Correspondent Mark D. shares some history on the weapons development process, and comments on "over-teching": I really enjoyed your comments on the defense industry. Both my parents worked for Lockheed, as well as several family friends during the days of the Tristar days, as well as the older, I forget the name of the passenger plane with the funny tail. they always complained about management sticking with Rolls Royce, and that, at the time, the strength of Lockheed was efficiency of design, efficiency of aircraft, though not in vogue at the time, turned out to be inconsequential, then, but not now. My Dad worked on the Aquila, something that actually got cancelled! I had a neighbor that worked for Ampex and helped minaturize the VCR for flight recording for bombers and was PISSED they sold it to the Japanese. now he makes 1/8 scale WWII RC fighters with EVERYTHING to scale including flaps, twisting landing gear etc.Since I'd discussed the relative merits of Boeing vs. Lockheed on the C-5a aircraft, I asked Mark for the views of the Lockheed retirees he knows. His answer sheds considerable light on another source of "waste": the over-spec'ing of every component: To a man, er woman, they all said Boeing would have done a good job, too. Most said cost overruns are underestimated based on waiting for security clearance while doing nothing, (average of 6 mos?), requirements on procurements, such as complying with the wood source of hammers, making sure the hammer can hammer (labor, etc). Based on some of this, wood source is known, but i don't think anyone would buy a hammer made out of teak or mahogony, but someone still has to run around wasting time making sure the hammer was purchased conforming to requirements. That list is not infinite, but not measurable.Kevin K. has some doubts that reforming Medicare to emphasize prevention would work: I was talking about your BLOG with a co-worker and even though it is sad to say, we both agree that most spending on "prevention" will do nothing.Kevin also recommended the recent film on the dumbing-down of America: Idiocracy James C. raises the issue of what therapies are being ignored in favor of profitable pharmaceuticals and surgery: Health care is the one topic that I get more up in arms about than economics and investments. Have you read Politics in Healing by Daniel Haley? Do you know about IV Chelation Therapy? The medical establishment in America has become one of the most shameful aspects of our society. Worthwhile treatments and preventative methods are cast aside because they do not generate enought profit. I know about Chelation because I have studied the subject for close to four years and have been using the treatment for over a year. It works and is, in my opinion and the opinion of many other patients that I have met at the clinic, a much more effective treatment than bypass surgery, drugs et. al.And this just in, from frequent contributor Aaron K., on Medicare waste: I'd like to add to the mix that base health care costs are anomalously high even without poor medical spending decisions, due to the employer-based tax structure of the system. I wrote an extensive essay on the matter here, titled as above:What an extraordinary range of commentary! Thank you readers, for your contributions and thoughtful contributions. January 24, 2007 Medicare Waste--50%? Correspondent Paul M. raised the issue of waste in Medicare vs. waste in the Department of Defense. It's an important question, but rather than focus only on the waste which can be measured (over-billing, paperwork, fraudulent charges, etc.) I'm going to to take a "big picture" view and ask: how much of that $400 billion actually alleviates suffering, heals/cures the sick, and improves the health of elderly Americans? Could we do better for much less money? The corollary question is: how much healthier would Americans be (of all ages) if we spent some of that $400 billion in other ways, say on prevention rather than after a person is already ill or disease-ridden? Medicare program costs have risen from $70 billion in 1985 to $162 billion in 1994 to $390 billion in 2007 and are estimated to rise to $500 billion in 2011. Adjusted for inflation, that $70 billion 20 years ago should only be $130 billion now, not $390 billion. Are we three times healthier than in 1985? There's a variety of metrics we could use, but we shouldn't rely too heavily on longevity, in my view; "quality of life" (though harder to measure) is what counts to the patient and his/her family. This is a long entry, but this is a program which will, in its current runaway form, bankrupt our nation. (thanks to correspondent John B. for this link): Bernanke Warns of Looming Deficit Crisis (MSNBC 1/18/07) Let's start with the fraud and waste which can be measured: over-billing, etc. This has been documented for years: Waste in Medicare, 1995 Here's a Washington Post series from 2005: Bad Practices Net Hospitals More Money; High Quality Often Loses Out In the 40-Year-Old Program Accreditors Blamed for Overlooking Problems Once Health Regulators, Now Partners All of this is IBD--Important But Dull. Let's face it--an astounding number of folks profit immensely from billing Medicare. It's the golden trough not just for large companies but small ones, too. My thesis here is more radical than just "Medicare is riddled with waste, fraud and poor practices." I think a strong case can be made that 50% of Medicare funds are wasted in the sense they do not improve the quality of patients' life but often degrade it further: patients are needlessly placed in harm's way by encouraging risky, useless or harmful procedures in hospitals teeming with incurable staph and other infectious agents, patients are loaded up up with a dozen or more drugs which have never been tested in such an interactive stew of other pharmaceuticals, regardless of the relatively low value of the drugs as curative agents, or even outright negative affects of such drugs and perhaps worst of all, funds which could have made a difference in preventative care earlier in the patients' lives are squandered on the patients' last few weeks or months, after they've contracted lifestyle diseases such as diabetes, lung cancer, liver diseases and heart disease. Lest you think I exaggerate, here is Page One of yesterday's Wall Street Journal on the growing evidence that stents--one of the most common operations for heart-disease patients-- are not helpful but actually detrimental: (subscription required, or go to your library and read the print edition for free): The Case Against Stents: New Studies Hint at Overuse There is an alternative to useless, expensive (and immensely profitable) surgical procedures like inserting stents, which is called the The Heart Healthy Lifestyle Program by Dean Ornish, MD. What's the problem with the Ornish Plan, which has been clinically proven to reduce heart disease? You can't make any money off it! How the heck can I make billions off useless stents, useless drugs and dangerous operations with lifestyle changes which are controlled by--gasp--the patient? Well, you can't, and that's why Medicare is a largely worthless waste of $390 billion (soon to be $500 billion): it pays for operations, drugs, devices and "care" which rarely cure diseases or benefit the patients' quality of life. It does, however, create a vast trough of money which fattens companies and "healthcare" businesses with billions in profit. Do you think I exaggerate? Take statins, drugs which are routinely prescribed to millions of Americans with high cholesterol. Well now it turns out--surprise!--these drugs have side effects which are long-term bad news, and even worse, lowering cholesterol doesn't seem to be the risk factor that the Medical Powers That Be assumed. Here is the Center for Medical Consumers: CHOLESTEROL SKEPTICS AND THE BAD NEWS ABOUT STATIN DRUGS These cholesterol trials also looked at total mortality, that is, the deaths from all causes, and found little difference between the study participants who tried to lower their cholesterol and those who did not. In other words, some clinical trials showed that the heart disease death rates were, in fact, lower among men who had reduced their cholesterol levels. But this benefit was offset by a higher rate of deaths from other causes.And what happens if you question this stupendously profitable status quo? Your research funding gets cut off: Bad News About Statin Drugs "Anyone who questions cholesterol usually finds his funding cut off," said Paul Rosch, MD, who started his talk with a reminder that half of all heart attacks occur in people with normal cholesterol levels. "Stress has more deleterious effects on the heart than cholesterol," said Dr. Rosch,In other words, statins may actually increase the risks of heart attack rather than lower them. So why doesn't the FDA announce that statins are dangerous and not helpful? Because the pharmaceutical industry would freak out that their billion-dollar gravy train would end. Take a look at this story for more: (thanks to correspondent U. Doran for this link) Cholesterol, Lipitor, and Big Government Meanwhile, thanks again to U. Doran, we have this New York Times story reporting that plain old vitamin B, Niacin, is effective in lowering cholesterol and safer than the statins: An Old Cholesterol Remedy Is New Again If you believe that statins and stents are rarities, then you need to check all the meds your elders are taking and delve deeply into their safety and efficacy trials. You will find most meds help only a subpopulation of potential patients, and the side-effects can be serious. Say a drug seems to do some good in 20% of the trial patients, and doesn't seem to do too much harm to the other 80%--it will be approved. But what if side-effects take longer than the trial length to appear? What if the drug is overprescribed because "we have to do something to help the patient"? What if it interacts negatively with other medications? None of this comes out until the damage is already done. And if you're skeptical that lifestyle changes actually work, (stop eating junk food, start eating real food, pursue modest regular exercise--you know the drill) then read this U.K. study in which people ate a "primitive" human diet: eating a primitive diet lowers weight, cholesterol, blood pressure. The participants' health magically improved in just a few weeks: lower weight, more energy, lower cholesterol, lower blood pressure--what's not to like? If there was a drug which did all this without side-effects, it would sell in the tens of billions. But there is no such drug, nor will there ever be such a drug. "Health" is not a single metric but a systemic condition of healthy food intake, healthy mind (i.e. not depressed or stressed out) and a lifestyle which includes regular exercise. There's nothing mysterious about the process of healing and getting healthy. But it does take jettisoning the entire American diet of French fries, high-fat, high-salt high-fructose packaged food. My own observation is that American packaged food (canned goods, frozen meals, etc.) are much saltier and sweeter than they used to be a few decades ago. On the rare occasion I eat a canned soup (a can someone gave us, since I never buy any packaged food), I am astonished at the high fat content, the high salt and/or the high sugar content. Read this for more: (thanks to correspondent U. Doran for this link) Does High-Fructose Corn Syrup Have to Be in Everything? We all know fast food is basically garbage--high fat, no anti-oxidants, low fiber, high-fat salad dressings for the "healthy salad" made with junk oils, etc. etc.--but basically the rest of the American diet--all packaged food, baked goods, soda, etc. etc.--is also not healthy. If you travel abroad a bit, you discover that other cultures still eat "real food"--actual vegetables and grains and meat which is purchased and prepared at either home or a restaurant. Yes, American fast food has made enroads elsewhere, and thus nations which had few obese young people are now seeing a rising number of unhealthy fat kids. Recall that "lifestyle" diseases like diabetes have shot up from near-zero a few decades ago to epidemic levels. Pima Indians who live in the U.S. have horrendous rates of diabetes, while their next-of-kin (same genes) across the border in Mexico have none. What else do you need to know about the causes of diabetes? Here's more on research on the Pima tribe: Obesity and Diabetes My own observation is that exercise is more important than generally credited. People in northern Europe eat a lot of meat, white bread and cheeses--food which by "health nut" standards should have put them in an early grave-- and yet their lifestyle of eating modest portions and walking (i.e. "French women don't get fat") make them just about as healthy (in terms of longevity and quality of life) as the Japanese and Okinawans who eat a diet low in red meat and dairy products. Various cancers have been linked to high-fat, high-protein diets, as has arthritis. I don't have the time to list all the links--do your own research. It's all there at your fingertips. Then there's my own personal experience of the elderly people I have known. My uncle seemed a bit frail, but stable, but he went in for some operation which was supposed to fix something. He died in the hospital. Our old friend Joe was told he had an aneurysm in his chest, and the doctors decided to "fix" it. He died in the hospital. I could go on, but you have your own stories, no doubt. I can honestly say that I do not know one elderly person who entered the U.S. Medicare/"healthcare" system with a health issue (or a supposed health issue) other than an infectious disease which could be knocked down with antibiotics or a parts replacement (inter-ocular lens, hip, etc.) and emerged "healed," "cured," or alive and well. Is this just bad luck on my part, or the reality nobody wants to talk about? Meanwhile, their last operation and intensive-care stay cost the taxpayers hundreds of thousands of dollars, and enriched the doctors, hospital, etc. Did the doctors feel they "had to do something" lest they be sued later? Very likely. Did the doctors feel they "had to do something" because their training stressed that over "first, do no harm"? Very likely. Did the soon-to-be dead patient willingly go in like a lamb because he trusted the doctors to make the right decision for him? Undoubtedly. Instead of this insane system which waits until you have a life-threatening disease and then treats it with operations that don't work and drugs which actually do more harm than good, what if Medicare was operated for the health of the citizenry rather than for the profit of the "healthcare" industry? Let's say $100 billion of the $400 billion was set aside for prevention. What if every American who turned 45 had to go in for a physical to qualify for future Medicare, and if they smoked, were obese, drank too much/were a druggie, had incipient heart disease from lack of exercise, etc., then they would be told, "We are partners in your health. We cannot fix illnesses like diabetes, alcoholism, lung cancer and heart disease later--we have to fix them now, and you have to do your part. And if you don't take any responsibility for your own health, well, the care choices under Medicare are limited. Frankly, the government isn't here to save you from your own unhealthy lifestyle." A followup exam and lifestyle assessment would be required at 50, 55 and 60, making sure the future Medicare recipient was doing all that he/she could to maintain their own health. And if they continued to smoke and carry 50 extra pounds of weight, they would be warned that Medicare didn't cover "lifestyle-induced" illnesses like lung cancer and heart disease. In other words, if you're not partnering up and doing your part, the government isn't going to save you. Instead of sugar-coating reality (is that all that Americans can stand now, sugar-coated reality?), they would be told:"What you ruined--your health--cannot be repaired with any amount of money, and so we're not going to support the illusion that there's a miracle cure or surgery. We will keep you comfortable." When did personal responsibility stop being part of healthcare? If you drink like a fish and get a DUI, your insurance skyrockets. If you continue to abuse alcohol and get another DUI, you're in big trouble. (In much of Europe, it's one strike and you're out: one DUI and you lose your license.) If you persist in destructive personal habits like drinking and driving, and you get nailed with a third DUI, you're out: your license is pulled and insurance--forget it. My family has a history of alcoholism, so I'm not being cavalier here. Alcoholism is a serious condition which is very tough to manage. My siblings and I are able to drink responsibly, but I have friends from similar families who are teetotalers. Whatever works--the main thing is to take responsibility for your own health and risk factors. Yet if you smoke, drink heavily, eat poorly, allow yourself to become obese and don't bother exercising, then there's no cost? The government is supposed to somehow "cure" you despite your abuse of your body and your forfeiture of any personal responsibility? Why? Why are you responsible for some things but not for your own health? This lack of patient responsibility is built into the system. The system is set up to "process" lumps of passive clay: cut 'em open, give 'em meds, send 'em home. Here's just one example. My 80-year old father has osteoporosis. For this he has been given various puffers and pills to take. But no one in Medicare, or the entire vast system it feeds, has ever demanded that he do anything himself to improve his condition, though what this is--simple exercise--is well known: Bone density sharply enhanced by weight training, even in the elderly. There is another fatal flaw in Medicare, and the entire U.S. "healthcare" industry: if you want to drive in a thumbtack, all you get is a sledgehammer. A close family friend was an internal medicine MD for decades in a busy urban hospital. He once told me that there was nothing wrong with half the people who came in to see him; they just wanted to talk. My own grandmother combatted loneliness and boredom with weekly visits to the doctor for vague ailments such as knee pain (Tylenol) and feeling low (anti-depressants, which never worked--why? Because she wasn't depressed). The doctor was pleased to bill Medicare for a 5-minute visit. If you think this isn't common, you need to spend more time with elderly people. An elderly friend we keep an eye on (she has no surviving family) goes to Kaiser Hospital on a constant basis for basically the same reason: it gives her something to do. She recently insisted on an operation on her hand, and surprise, surprise: now her hand hurts more, and only closes halfway. My father fell and fractured a bone last year, and so he spent a week in a rehab clinic. The gentleman with whom he shared the room had no real reason to be there; since we were with my Dad every day, we started talking to this gent. Turns out his daughter worked all day, and so he was lonely. Every few months he'd conjure up a reason to go into this rehab clinic (at hundreds of dollars a day) just for some human companionship and stimulation. So what we have is lonely seniors, and what we offer is horrendously expensive medical "care" for their relief: a sledgehammer for a thumbtack. What depressed seniors need is a ride to the senior center, to join a depression management group, etc. This would be so much cheaper--and kinder, and more effective--than giving them a basically free visit with a doctor who then feels obligated to "do something" which ends up being costly, useless or even detrimental. Personal responsibility seems to be a lost value in American life now. Hey, we all want to eat a quart of ice cream and gobble down chips and fries--they taste good, and in fact are engineered to taste good. (Have you ever noticed that the labeling on animal feed is more detailed than the information provided on human food?) But there's a cost to eating junk, so we can't indulge in irresponsible eating any more than we can indulge in irresponsible drinking. I like ice cream as much as the next sweet-tooth, but I eat it a couple times a year, at birthday parties. Do I miss it? Occasionally. Ditto the other things I no longer eat except on rare occasions--doughnuts, chips, fast-food burgers, etc. But is our life ruined by foregoing all this stuff? I think it's abundantly clear that it's ruined if we eat it as often as our taste buds (and emotional situations) desire. What's sad (or ironic, if you're cynical) is that once you get overweight and contract diabetes--and yes, I do have friends with diabetes--then you can't eat that stuff anyway, but now you have to monitor your blood sugar and worry about losing years off your life. Yes, many diseases are genetic and "not my fault;" I'm fair-skinned so I am at risk of skin cancer, even though I wear sunscreen and a hat every day. African-American men are at higher risk of prostate cancer, and so on. The lens in our eyes cloud up with age, and have to be replaced with a plastic lens. Fine; that's not too costly. Hips and knees give out earlier in some of us than others (not always from carrying around an extra 50 pounds, but that certainly doesn't help.) Fine. It's straightforward to diagnose, the cost is standardized and the pay-off is immense. We all have medical conditions which may rise up into crisis even if we have led a healthy lifestyle. Yes, Medicare should pay for the treatment of these diseases and body-part replacements. But how much of the $400 billion is actually spent on this type of care, and how much of it is actually effective? How much is worthless MRI tests so the clinic won't be sued later for "not doing everything possible"? So here we are: as a nation, we spend 16% of our $13 trillion GDP on "healthcare," and will very shortly be paying more for Medicare than the entire Military and V.A., yet it is clear we are an unhealthy nation: poor child mortality rates, high obesity rates (either 40% or 60% of the adult population is overweight, depending on your metric) and so on. There have been public health victories: smoking has receded, greatly improving the lives and longevity of those who quit and those who live with them. Some genetically caused cancers, such as aggressive breast cancer, have improved drug treatments. Yes, some pharmaceutical research does result in drugs which improve the patient's life--but not as many as you might think. A close friend's wife just went through surgery for colon cancer. My friend is a physicist by training so he did voluminous, painstaking research on the pros and cons of chemotherapy. He concluded that the difference in the 5-year and 10-year survival rates for those who endured chemo and those who did not were statistically insignificant. In other words, a horrendously difficult and expensive treatment which is recommended without hesitation by the "establishment" has very little chance of prolonging the patient's life, though it puts the patient through six months of Hell. This is not some outlier; this is common. The conclusion: we pay trillions for medical care which doesn't work or actually makes us sicker, more at risk of illness or just flat-out kills us. Medicare is an insane system in which the government does virtually nothing to educate (or cajole) people into improving their life through preventative lifestyle improvements, but waits until the person is old and ill, and then it expends hundreds of thousands of dollars on the person's last days, wasting the money on illusory "solutions" and robbing the patient of their dignity and the opportunity to die in hospice or at home. If we set out to design a more wasteful, destructive, useless system, I don't think we could do better than the current Medicare system. My own personal experience suggests that we'd actually be better off if Medicare simply went away and was replaced with a preventative-care system which sought to identify risks in middle age (or even sooner) and enrolled the patient in a partnership of health. Thank you, Paul, for raising the issue of waste in the Department of Defense and Medicare. I hope I have found some links which have added to readers' knowledge. January 23, 2007 A Closer Look at Department of Defense (DoD) Spending Correspondent Paul M. challenged me to back my (wild, unsubstantiated) assertion that the DoD budget contains less waste than Medicare. This is important, so please follow along with an open mind. There are plenty of links for further reading. Today I offer a glimpse into Pentagon spending. Please note that the Pentagon is a civilian agency. The U.S. Armed Forces do not budget the money or assign the contracts: this is done by civilians under the control of the President and Congress. Please keep this separation in mind. My stepfather was career Air Force, and I learned this distinction is key in any analysis of spending and "waste." (One person's waste is another person's job--and don't forget who controls spending: politicians, not Generals and Admirals.) As for Pentagon waste: I am skeptical of both the spending and the claims that it can easily be slashed. The issues are very complex and I will try to lay out the most important ones for your review and comment. Based on my own extensive readings, I believe most of the Service (Army, Navy, Marines and Air Force) leaders are acutely aware of shrinking budgets and the need to get "lean and mean" in staffing and hardware. To take but one example: the new DDX Destroyer will require a crew of 150 or so, 70% smaller than the one required to operate the current destroyer fleet. Since according to the GAO (see below), crew costs are the largest expense over the life of the ship, this reduction in crew size is a truly massive savings. GAO DDX analysis Navy's DDX site The DDX is a revolutionary ship design which is an essential step forward in an era of cheap over-the-horizon missiles of the Exocet type: it's form factor radically reduces its radar signature, and its propulsion drive radically improves efficiency. The rest of world, including potential threats such as China, are not standing still. If you're going to have a military, then you want to enable it to win should conflict become unavoidable. Please glance through this detailed article, for it says so much more than a description of this one ship class: DDG-1000 Zumwalt / DD(X) Multi-Mission Surface Combatant Future Surface Combatant (globalsecurity.org) Note that the U.S. Navy had about 600 ships in the Reagan-era build-up 20 years ago, and has declined to 375 ships. In other words, the Cold war dividend has already been paid in full. Now the fleet is scheduled to decline to 325 ships or less, and many (including this taxpayer) are concerned that it's simply not enough to maintain unchallenged control of the seas. There have been studies (none I could locate today) which correlated overwhelming military superiority to peace, and military parity with war. In other words, if potential adversaries (such as China) sense that they can reach rough parity with your forces, then they are tempted to do so, and tempted to risk war. If they are hopelessly outclassed and outgunned, then they are unlikely to call your bluff. This makes perfect sense. Thus the best way to avoid war with China or any other nation is to maintain overwhelming superiority. And as Stalin is proported to have said, quantity has its own quality. In other words, if you have six fine ships facing off against 40, odds of victory, no matter how excellent the ships and crew, are seriously diminished. At a minimum, you'll simply run out of weapons. The globalsecurity.org article mentions several other key issues. The Navy wanted a winner take all contract, but Congress refused. Why? Because they need to spread the spending around, and as the fleet has shrunk, so has the number of shipbuilders. There are now only two in the U.S., which is a troubling statistic. As for submarines--if we stop building subs (and the fleet is already too small, in many analysts' opinions), then the workforce which disappears cannot be replaced. The knowledge of such complex machines cannot be re-stablished later without mistakes being made and much treasure expended. To put it bluntly--much of the Pentatgon waste is a result of political meddling, otherwise known as "pork." I have seen studies which showed that Defense contracts go not to the best qualified contractors, but to whichever contractor is about to go bust. Thus the C-5a cargo aircraft should have been built by Boeing, which had the expertise to build superjumbo planes; but Lockheed was hurting, so they got the contract. The result: massive cost overruns and numerous quality issues with the aircraft. But it was politics all the way down the line. This is not trivial. According to this article, the cost of outsourcing the ship to two suppliers will raise the price by $300 million a ship. That's not Pentagon waste, that's Congressional waste dumped on the Pentagon's lap. The Navy has to suck it up and cut their budget somewhere else so their political overlords can go home and brag about the pork they brought home to their district/state. there's another politically motivated cause of waste: Congress doesn't want to budget the full costs of a weapon system in one year, because it ruins the illusion they try to maintain about being budget-conscious. So weapons procurement budgets are stretched out for years, boosting the overall costs of the system. As any business owner knows, overhead is a daily expense; if you could build three ships a year but you're told to do only 1.4 (yes, not even two), then your overhead costs eat you alive. The ships end up costing millions more just so Congress can keep the budget line item per contract artifically low. If we wanted to save money, we'd budget the full $10 billion for the ships and have the yards build them as fast as was efficiently possible, not drag the procurement out over 10 years so it appears to be only $1 billion a year. On the other hand, I am troubled by the F-22 Raptor aircraft contract, which has ballooned from $86 million per aircraft to $300 million per plane. F-22 overruns GAO report on the F-22 More on the F-22 The story includes the usual budgetary legerdemain mentioned above, of course, but it also highlights the "mission creep" syndrome in which a new weapons system gets loaded up with more and more missions, often rendering the final package unwieldy and costly. The F-22 is the replacement for the F-15, and it shares many of the F-15's worst traits: a long lead time (the F-22 was started in 1986 and given the go-ahead in 1991), and the complexity of its missions and avionics. The basic idea is: to save money, get one plane to do it all: bomber, fighter, all-weather, long range, etc. etc. That's how planes end up taking 15 years to produce, and cost $300 million each. Even worse, the F-22 is only supposed to be a "stop gap" aircraft until the deployment of the next generation F-35 Lightning. F-35 description An alternative way was illustrated with the F-16, a light, one-pilot air superiority airplane designed by "fighter jocks." It was designed in a relative hurry and went into production in a hurry, and as a result it was far cheaper than the heavier, two-pilot F-15. The F-16 wasn't all things to all people; it was designed to shoot down the bad guys and achieve air superiority. Its bomb load was limited, as were its avionics and range. Maybe the U.S. needs a "fighter jock" designed replacement for the F-16 more than it needs a horrendously expensive "does it all" aircraft like the F-22. Do weapons systems get cancelled? The cliche is that they don't, but they do. The Army's poorly named Crusader cannon was cancelled, as was the Navy's A-12 aircraft. Not all programs are expensive flops. the F-18 Hornet went through an extensive redesign which lengthened the aircraft, extended its range, upgraded the engines to more powerful yet more efficient engines, and upgraded the avionics package. As a result, the Super Hornet can handle missions which in the Vietnam Era required no less than 10 different aircraft. Wikipedia's entry for the F-18 the Navy's entry for the F-18 weapons load out graphic (all the various munitions the aircraft can carry) The F/A-18 E/F acquisition program was an unparalleled success. The aircraft emerged from Engineering and Manufacturing Development meeting all of its performance requirements on cost, on schedule and 400 pounds under weight. All of this was verified in Operational Verification testing, the final exam, passing with flying colors receiving the highest possible endorsement. The Super Hornet cost per flight hour is 40% of the F-14 Tomcat and requires 75% less labor hours per flight hour.Then there are the other DoD items which no one seems to know about or consider. The Veterans Administration is tasked with providing care to every veteran who seeks care, and that numbers in the millions. The VA budget is $35 billion a year, and should be higher. The VA's website The VA's budget Then there's all the fundamental scientific research which is appropriated under the Pentagon, even though it benefits the nation in much the same fashion as the National Science Foundation grants. These include DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Programs Agency) DARPA's budget which is reliably criticized for various goofy research ideas-- www.defensetech.org But which also funds robotics and other fields of non-military value. The Office of Naval Research funds programs as varied as astronomy and drug development. ONR website Then let's not forget that some of the Homeland Security boondoggle (talk about waste and fraud) has been slipped onto the Pentagon ledger, fairly or unfairly, it's hard to tell. Though few mention it, the Iraqi War has drawn down the military's logistics, burning through equipment including National Guard stocks which are not being replaced. Lastly, the "black budget" spy/intelligence programs are funded by the Pentagon, to the tune of perhaps $10 billion or so. Nnobody knows, everyone guesses; The C.I.A. also has "black budget" items.) To summarize: the U.S. Military is tasked with winning whatever war its political masters (the President and Congress) choose to wage or engage, be they all-out wars with nuclear-armed opponents or "low-intensity" conflicts in distant parts of the globe. While considerable waste can be laid at the feet of a Pentagon (a civilian agency, recall) without sufficient oversight, wasteful contractors, etc., much more can be laid to political machinations. Why does the Military have offices in West Virginia? Look no further than Senator Byrd. Does Texas or California "deserve" this spending? No more than West Virginia. The point is that the Military's recommendations for saving money in basing are generally ignored. Given the scope of the U.S. Military's mission and the number of its personnel and retirees, to say it should/could operate on half its current budget does not align with the complexity of the threats the Military is tasked with countering. It can be argued that the Department of Defense's share of the U.S. GDP and Federal budget is near postwar lows. It consumed 7.5% of GDP in the Cold War years, and now accounts for about 4%. Heritage Foundation commentary on DoD spending The 2007 Defense budget is $439.3 billion, about the same as Medicare, which is $395 billion and rising rapidly. The cost of Medicare is set to explode. Under current law, Medicare spending is projected to jump from $395 billion in FY 2007 to $504.4 billion in FY 2011 and to total roughly $2 trillion over that same period. source: Heritage Foundation commentary on Medicare spending The entire Federal budget is $2.77 trillion. Here's a good listing and chart: Federal Budget for 2007 The Interest on the National debt for 2007 is $243.7 billion--a 13.4% increase. I find it appalling that plenty of people complain about DoD spending at $440 billion (of which perhaps $100 billion is VA, research, retirement, black-budget intelligence, etc.) but they rarely mention the rapidly increasing cost of servicing the debt. If you compare Defense budgets as a percentage of GDP or Federal spending, you have to conclude the deficit is not caused by Military spending, which has declined percentage-wise, but on the skyrocketing costs of social entitlements like Medicare. So feel free to blast Pentagon "waste," but please educate yourself on the missions, staffing, weapons systems, threats and political meddling involved if you want to engage in a thoughtful debate. I suggest that DoD spending--yes, there is waste, as there is in any vast government program--still delivers the results which the nation demands: military superiority via the ability to project power anywhere on the globe. In contrast, Medicare consumes roughly the same amount of money and delivers so little: we are not a healthy nation, but a sickly one, and the funding is largely wasted on procedures and drugs which do little good and often do tremendous harm. If the Armed Forces and the VA were cut in half, I fear for our nation; if Medicare were cut in half? I'm not so sure. More on that tomorrow. January 22, 2007 Tax Rates and Tax Waste You, dear reader, do not tolerate unsupported claims or muddled thinking--much to my benefit. You make me do more research and clarify my thinking, for which I'm grateful. My recent entry on taxes brought a number of thoughtful responses, politely calling me to explore issues left unaddressed or back up unsubstantiated claims.

First up is astute reader Greg B., who questioned the moral basis for high taxes: I began reading your blog because I agreed with your thesis that the Federal Government was the cause of most of our problems (too low Fed Fund rates, loose lending standards, excessive spending, etc.)Excellent point, Greg, for "no taxation without representation" lies at the heart of the American Republic. We the people have the right to set our own taxation, and to direct or approve the spending of that taxation. This is a key moral foundation of our Republic. What I should have said was something like this: I morally object to borrowing trillions to pay benefits to ourselves and then offloading the payment of that debt to our children and grandchildren. What we as a people seem to want (based on the gutless "leaders" we elect to high office) is low taxes but plump entitlements--in other words, we want to have our cake and to eat it, too. Of course no nation can offer its citizens low taxes and rich entitlement benefits, and so we have collectively borrowed trillions of dollars in the form of Federal borrowing to make up the difference. But all debt carries interest, and an astounding $192 billion already goes to pay interest on the $8 trillion in Federal debt we've borrowed to balance our national income with our desired benefits. Please see the chart above for the train wreck which lies just ahead and read an earlier entry on The Real Federal Deficit: $2.3 trillion a Year (June 2005) As for the interest payments on that stupendous debt, according to the Federal Government, it now totals $405 billion a year. About half of this is transfers within the government, "paying interest to itself," but the outlays to outside holders of debt are nearing $200 billion a year. That's more than half of Medicare's $390 billion budget. Yet no one squawks at all about this massive transfer of funds to support deficits--deficits which are sure to climb as out-of-control entitlement spending leaps with Baby Boomers' retirement. We want Free Enterprise and low taxes when we're making money, and Socialism when it comes time to collect "our" Social Security and Medicare benefits. Let's face it: Social Security was always a generational 3-Card Monte gamble. When it started, there were something like 40 workers for each retiree; now that's down to about 3 workers per retiree. The gamble depended on ever rising numbers of workers entering the system to keep the retiree-worker ratio high. The Baby Boom enabled the system to continue for decades, ballooning the workforce with its huge cohort of 70 million, but now that the "pig in a python" (the 70 million boomers) is set to retire, the ratio will slip to an unsustainable 2 workers for every retiree. Back in the '30s, when Ma and Pa Kettle retired at 65, they lived to 67 (actuarily) or so before going to their rewards. Now we retire at 62 and live to 82. It doesn't take much common sense to see that a system set up for a few years of modest retirement cannot possibly carry retirees for decades. For more on this subject, please read two books on my Recommended List: Fewer: How the New Demography of Depopulation Will Shape Our Future The Coming Generational Storm: What You Need to Know about America's Economic Future And don't even get me started on the SSI "crazy money" and all the other welfare programs which have been offloaded onto Social Security to tap all those surpluses without having to allot discretionary funds. The system is set to implode, and I am skeptical of claims that all is well until 2060. Recall that the Social Security surpluses are being spent on other Federal spending, so once the surpluses vanish (which will be soon), then the shortfall will come from the same source we depend on so mightily: borrowed money, mostly from the rest of the world. Yes, there is a moral imperative for the government to justify its taxation and spending, but there is also a moral imperative for the citizenry to not offload its own profligate spending onto future generations. Thank you, Greg, for bringing the moral aspects of taxation to the fore and making me clarify my own position. Nexr up, frequent correspondent Michael Goodfellow asks for data on the total tax burden, and for some accountability on spending: You'd really have to include state and local taxes in your effective tax rates, especially if you are going to compare internationally. The U.S. states are as large as many countries, and provide a significant portion of services.Fortunately, correspondent U. Doran supplied this account of our total tax bill, including state and local taxes; by this reckoning, we already pay 54%: How much tax do we really pay? Next up: correspondent Paul M. politely calls me to account for my claim that Medicare spending surpasses the gross mismanagement of funds within the Pentagon: I must take issue with some statements you made about our deficit in your January 19, 2007 entry, the most unsupportable one contending:Thank you, readers, for sharpening the issues and providing excellent data on tax-related issues. I will take up Paul's question about Pentagon and Medicare waste tomorrow. January 19, 2007 Tax Rates: Are The Rich Really Different? In response to yesterday's entry on maximum tax rates, knowledgeable reader Michael M. noted that the more telling statistic is the effective tax rate: (i.e. what people actually pay) As a tax professional I can assure you that comparing highest statutory income tax rates year over year is meaningless. A better comparison would be average effective tax rates for example or gross income tax receipts in real dollars.Michael was kind enough to send over some links to CBO (Congressional Budget Office) data: CBO Publications Here is the link specific to the historical average effective tax rates from 1979 to 2001: Effective Federal Tax Rates, 1979-2001  The top 1% had an effective rate of 37% in 1979, which dropped a bit to 33% in 2001.

The bottom 20% paid 8% in 1979 and 5.4% in 2001. In other words, everyone's effective

tax rate dropped by about 2% or 3%. That's about a 10% drop for the top 1% and a 30% decline

for the bottom 20%. Sounds good, but then if your tax bill was $500, a 30% drop works out

to $150. Not bad, but not much. If your tax bill was $5 million (remember we're talking

about the 1% who owns 60% of all productive assets in a $13 trillion economy with a net worth

around $50 trillion) then a 10% drop in your tax rate comes to $500,000. Not much if you

own tens of millions in assets, but nothing to sneeze at, either.

The top 1% had an effective rate of 37% in 1979, which dropped a bit to 33% in 2001.

The bottom 20% paid 8% in 1979 and 5.4% in 2001. In other words, everyone's effective

tax rate dropped by about 2% or 3%. That's about a 10% drop for the top 1% and a 30% decline

for the bottom 20%. Sounds good, but then if your tax bill was $500, a 30% drop works out

to $150. Not bad, but not much. If your tax bill was $5 million (remember we're talking

about the 1% who owns 60% of all productive assets in a $13 trillion economy with a net worth

around $50 trillion) then a 10% drop in your tax rate comes to $500,000. Not much if you

own tens of millions in assets, but nothing to sneeze at, either.