|

| articles | forbidden stories I-State Lines resources my hidden history reviews | home | ||

Writing/Film Dear Aspiring Writers: The Worst Advice You'll Ever Read A Literary Look at I-State Lines Spirited Away: Decay and Renewal An American Poem (Robinson Jeffers) Taoist Chinese Poems The Nelson Touch "It's all about oil, isn't it?" Kurosawa's High and Low A Bountiful Mutiny Howl's Moving Castle Thailand's Iron Ladies Trois Colours: Red The Thin Man: Thoroughly Modern Movies Why My Book Is Better Than the DaVinci Code 9 more in archive Recommended Books American Identity Hapas: The New America Can You Tell What I am? Part I Can You Tell What I am? Part II Only in America Self-Reliance Your Tattoo in 50 Years The American House and Frank Lloyd Wright Cultural Commentaries On Hatred and Anti-Americanism Anti-Americanism Part 2 Anti-Americanism Part 3 French-Bashing Germany: We All Have Problems, But... Kroika! Chronicles This Blog Sells Out Doom and Gloom Sells The Kroika Mascot-"Auspicious Pet" Wal-Mart and Kroika Kroika and Starsbuck Take a Hit Kroika Ad 1 Kroika Ad 2 Kroika Ad 3 Kroika Ad 4 Kroika Makes Bid for Oreo (April 1) Unfolding Crises: Asia China: An Interim Report Shanghai Postcard 2004 Corruption and Avian Flu: China's Dynamic Duo Exporting the Real Estate Bubble to China Is the Bloom Off the China Rose? China Irony: Steel, Marx & Capital Curing The U.S. and China's Dysfunctional Relationship China and U.S. Inflation Trade with China: Making Out Like a Bandit Whither China? 8 more Battle for the Soul of America Katrina, Vietnam, Iraq: National Purpose, National Sacrifice Is This a Nation at War? A Nation in Denial Why Is This Such a Tepid Time? That Price Isn't Cheap, It's Subsidized U.S. Fascists Seek Ban on Cancer Vaccine The Truth About Christmas American Dream or American Nightmare? The Most Hated Company in America 2006 Sea Change Obesity and Debt Immigration Ironies U.S. Healthcare: Working Toward a Real Solution 10 more Financial Meltdown Watch What This Country Needs Is a... Good Recession Are We Entering the Next Age of Turmoil? Why Inflation Appears Low Doubling Down on 5-Card No-See-Um A Rickety Global House of Cards Are Japan and Germany Truly on the Mend? Unprecedented Risk 2 Could One Rogue Trader Bring Down the Market? Worried about Inflation? Stop Measuring It Economy Great? Bah, Humbug Huge Deficits and Huge Profits: Coincidence? Who's The Largest Exporter? Three Snapshots of the U.S. Economy Loaded for Bear Comparing Nasdaq to Depression-Era Dow Who's Buying Treasury Bonds? And Why? Derivatives: Wall Street Fiddles, Rome Smolders Financial Chickens Coming Home to Roost Is the Stock Market on the Same Planet as the Economy? 31 more Planetary Meltdown Watch The Immensity of Global Warming Sun Sets on Skeptics of Global Warming Housing Bubble Watch Charting Unaffordability A Monster of a Housing Bubble A Coup de Grace to the Economy Hidden Costs of the Housing Bubble Housing Bubble? What Bubble? Housing Bubble II Housing Bubble III: Pop! Housing Market Slips Toward Cliff Housing Market Demographics Housing: Catching the Falling Knife Five Stages of the Housing Bubble Derailing the Property Tax Gravy Train Bubbling Property Taxes Have You Checked Your Property Taxes Recently? Housing Bubble: Where's the Bottom? Housing Bubble: Bottom II The Housing - Inflation Connection The Coming Foreclosure Nightmare 1 How Many Foreclosures Will Hit the Market? Housing Wealth Effect Shifts Into Reverse Housing Bubble Bust Will Take Down the Global Economy The New Road to Serfdom: A Negative-Equity Mortgage The Housing-Savings-Recession Connection After the Bubble: How Low Will It Go? After the Bubble: Rents and Housing Values Why Post-Bubble Rents Matter After the Bubble: How Low Will We Go, Part II Housing: 10% Decline May Trigger Financial Ruin How to Buy a $450K Home for $750K The New Road to Serfdom: A Negative-Equity Mortgage Inflation and Housing: Calculating the Bust The Growing Financial Risks of the Housing Bubble 10 more Oil/Energy Crises Whither Oil? How much Is a Gallon of Gas Worth? The End of Cheap Oil Natural Gas, Naturally High Arab Oil Money and U.S. Treasuries: Quid Pro Quo? The C.I.A., Oil and the Wisdom of Crowds The Flutter of a Butterfly's Wings? A One-Two Punch to a Glass Jaw Running Out Of Oil vs. Running Out of Cheap Oil 2 more Outside the Box How to Make a Favicon Asian Emoticons In Memoriam: Winky Cosmos The Wheeled Vagabonds Geezer Rock Overload In a Humorous Vein If Only Writers Had Uniforms Opening the Kimono Happiness for Sale: Jank Coffee Ten Guaranteed Predictions for 2010 Why My Book Is Better Than the DaVinci Code Design Follies The New Jank Coffee Shop Jank Coffee, Upscale Tropic Style One-Word Titles Complacency Nostalgia Praxis Keys to Affordable Housing U.S. Conservation & China Steve Toma, Me & Skil 77s: 30 years of Labor Real Science in the Bolivian Forest Deforestation and Sustainable Forestry The Solar Economy (book) The Problem with Techno-Fixes I Love Technology, I Hate Technology How To Blow off Web Ads and More 2 more Health, Wealth & Demographics Beauty of the Augmented (Korean) Kind Demographics and War The Healthiest Cold Cereal: Surprise! 900 Miles to the Gallon Are Our Cities Making Us Fat? One Serving of Deception Is Obesity an Inflammatory Response? Demographics & National Bankruptcy The Decline of Europe: A Demographic Done Deal? Are the Risks of Obesity Overstated? Healthcare: Unaffordable Everywhere The New Disease We Just Know You've Got 2 more Landscapes Selling the Landscape The Downside of Density Building Heights and Arboral Roots Terroir: France & California L.A.: It's About Cheap Oil The Last Redwood Airport Walkabouts Waimea Canyon, Yosemite, Camping & Pancakes Nourishment The French Village Bakery Ideas What Is Happiness? Our Education System: a Factory Metaphor? Understanding Globalization: Braudel Can You Create Creativity? Do Average People Know More Than Their Leaders? On The Impermanence of Work Flattening the Knowledge Curve: The "Googling" Effect Human Bandwidth and Knowledge Iraqi Guangxi Splogs, Blogs and "News" "There is no alternative to being yourself" Is There a Cycle to War? Leisure, Time and Valentines Is the Web a Giant Copy Machine? History The Strolling Bones: Rock of Ages Bad Karma: Election Fraud 1960 Hiroshima: First Use All the Tea in China, All the Ginseng in America Friday Quiz Pet Obesity The Origins of Carbonara Organic Farms Oil and Renewable Energy Human Diseases Wine and Alzheimers Biggest Consumers of Chocolate 7 more Essential Books The Misbehavior of Markets Boiling Point (Global Warming) Our Stolen Future: How We Are Threatening Our Fertility, Intelligence and Survival How We Know What Isn't So Fewer: How the New Demography of Depopulation Will Shape Our Future The Coming Generational Storm: What You Need to Know about America's Economic Future The Third Chimpanzee: The Evolution and Future of the Human Animal The Future of Life Beyond Oil: The View from Hubbert's Peak The Party's Over: Oil, War and the Fate of Industrial Societies The Solar Economy: Renewable Energy for a Sustainable Global Future The Dollar Crisis: Causes, Consequences, Cures Running On Empty: How The Democratic and Republican Parties Are Bankrupting Our Future and What Americans Can Do About It Recommended Books More book reviews Archives: weblog May 2006 weblog April 2006 weblog March 2006 weblog February 2006 weblog January 2006 weblog December 2005 weblog November 2005 weblog October 2005 weblog September 2005 weblog August 2005 weblog July 2005 weblog June 2005 weblog May 2005 What's New, 2/03 - 5/05

|

|

June 30, 2006 Where Is This?  *

** * * * * * * * * * This is what's known as "sharkbait"--tasty white meat on a beach somewhere, looking unhealthily pale. So where is this sharkbait standing? Alas, the paleness is genetic and cannot be fixed by frolicking in the sun. Note the hat and late hour of the day (scars from skin cancer surgeries are not visible, thank goodness). And yes, that is SPF 40 on the sharkbait skin. My surfer friend G.B. turned me on to Aloe Gator Total Sunblock Lotion, and it really is waterproof. This location is just too easy for those residing in a certain state whose name shall go unmentioned, but visitors may not have wandered down to this largely ignored (and therefore peaceful) strip of sand. At the nadir of my starving student days (i.e. emptying my childhood coin collection to buy a couple gallons of gasoline for my crummy VW Bug), I lived just a few blocks from this beach in a guest cottage stuffed with the owner's business records. I literally had to thread my way through stacked boxes of tax records to get to the tiny bathroom. But the price was right and I managed to survive the recession of 1973-74. (This practise will help me survive the recession of 2007-11.) Typically I pitch my little novel I-State Lines on Friday, but since yesterday's subliminal campaign failed utterly, I am too despondent to even work up a pitch. Instead, let's get another perspective on "paying for Web content" from an akamai correspondent who had this to say regarding my recommendation to subscribe to patrick.net's new fee-based service (see yesterday's entry for context): Really? $75 a year for a page full of links that other people send him? Hardly seems like original content, or time-consuming either. The stuff you write is 10X more creative than a simple "link farmer" assembling a list of pages based upon what other people send him. Heck, the entire content of the WSJ online is $79/year. I would subscribe to patrick.net for something like $10/yr, but $75 no way, just out of principle - there's no creativity involved whatsoever. Heck, next month, someone else (maybe me) will start compiling links of housing stories.I think the source of irritation is clear--assembling links does not qualify as original content to this reader, and I can understand that view. The Web is littered with failed attempts to get users to pay for content, and I am not sure that the current fad of placing contextual ads on sites will succeed in the long run, either. That doesn't stop me from trying it, too, of course. So twist your doctor's arm into writing a prescription for Zombiestra (TM), "Because Life's a Beach" (TM, Astra-Zastra). See how that works? I mentioned "beach" in today's entry, and my handy-dandy ad placement script quickly identified this as the perfect time to insert Zombiestra's catchy slogan, "Because Life's a Beach" (TM). Be the first to identify this specific beach, and I'll send you a collector's copy of my book I-State Lines. So email me! June 29, 2006 Paying for Web Content  I recently received a very kind offer of a Paypal donation from a true gentleman,

Jan-Martin of Germany. (According

to my website logs, I have had readers from 89 nations this month.)

I recently received a very kind offer of a Paypal donation from a true gentleman,

Jan-Martin of Germany. (According

to my website logs, I have had readers from 89 nations this month.)

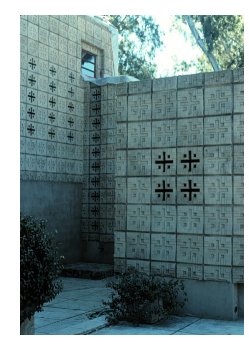

I understand the need of other sites to either charge for content or sell ads to defray the expenses of operating the site, not to mention compensation for the content. One of the key referral sites for my own, patrick.net, just transitioned from a free (and very time-consuming to assemble) resource on the housing bubble to a low-priced subscription format ($10 for 50 daily reports.) I recommend subscribing to patrick's service, which is both highly informative and very modest in cost. Few bloggers can afford to provide substantive, original content with no compensation or ad revenue. I get many emails thanking me for my offerings, and asking how I manage to write so much so often. The answer? I am a complete idiot. Only a real moron would write so much for nothing, and alas, if there is any financially rewarding way to do anything, I will stumble into the opposite corner. (See My Brand Management Stinks, June 22, below.) I know this sounds cliched, but the quality of my readers is my reward. I am continually astonished and delighted by the intelligence, knowledge, acumen and writing ability of my readers. And since I reckon a site free of any direct monentary compensation is truly independent, I declined Jan-Martin's generous and kind offer of a donation. Not only that, but I am offering my long-suffering readers a bonus--a high-quality piece of art which is suitable for printing and framing (see above). If you examine this fine work of art long enough, you might be overcome with the unquenchable desire to own a copy of my little novel, I-State Lines from either an independent bookstore, The Kaleidoscope: Our Focus Is You or from amazon.com Now if you, of your own free will, unencumbered by subliminal suggestions or advertising, suddenly and irrevocably decide to purchase a copy of my novel ($20 from Kaleidoscope, shipping is free), then yes, I will eventually receive about $1 from my truly admirable husband-and-wife "30 years of literary publishing" publisher, The Permanent Press (Please check out their current list of novels and extensive backlist of modern and classic fiction.) As an Amazon Associate, I do earn a modest referral fee should you buy any of the books/films I recommend, but these are modest indeed--as little at 8 cents on a used book and perhaps 40 cents for a new book. These fees come from Amazon and do not raise the price of your purchase. To date I have earned about $33 from readers' purchases this year, a not quite stupendous sum which I do not expect to arouse great envy in my readers. As I am quick to point out, you can always borrow any book for free from your local library (if cutbacks and rising benefits costs haven't completely gutted the hours it is open to the public). In all seriousness: if you'd like to try some new, unknown fiction (or want to shove a mildly amusing literary novel toward some young person of your acquaintance), then maybe you'd like I-State Lines. If not, this site remains free of charge to you. I do, however, suggest that you stare deeply into the formidable piece of art above, and let your subconscious mind play upon its patterns. You do want to buy a copy of my book now, don't you? You find it fascinating, don't you? Compelling, in a strangely irresistable fashion? Well, don't let me stop you; it's your decision. June 28, 2006 Will the Housing Bust Take Down China?  Is China dependent on the U.S. consumer economy? This chart supports the obvious

answer: Yes.

Is China dependent on the U.S. consumer economy? This chart supports the obvious

answer: Yes.

And what is the U.S. consumer economy dependent on? Equity extracted from rising housing values. (see chart below.) And what is the result of the housing bubble deflating? No more equity extraction, and hence a drop in consumer spending and housing/lending-related employment. Shall we connect these two dots? As the housing bust drags the U.S. into a deep consumer-led recession, it will take the Chinese economy with it. There are a number of dynamics to consider, but this is the primary one: China depends heavily on its export market for the profitability and growth of its economy, and on the influx of foreign investment which has fueled that sector's white-hot growth.  Recall that some 40% of China's growth is direct foreign investment. Are these investors

pouring money into domestic markets such as agriculture and low-cost consumer good made

for the Chinese market? Of course not; the SOEs (state-owned enterprises) and other Chinese

companies have long been supplying inexpensive TVs, clothing, refrigerators, motorbikes, etc.

for the domestic economy.

Recall that some 40% of China's growth is direct foreign investment. Are these investors

pouring money into domestic markets such as agriculture and low-cost consumer good made

for the Chinese market? Of course not; the SOEs (state-owned enterprises) and other Chinese

companies have long been supplying inexpensive TVs, clothing, refrigerators, motorbikes, etc.

for the domestic economy.

With the exception of the automobile market, foreign investment--joint ventures, new factories, etc.--is largely aimed at the export market: building stuff in China to sell elsewhere. What happens to those hundreds of billions of foreign investment when exports to the U.S. plummet? It will drop, too, of course; why build yet another factory or distribution center when sales are falling? Do factories close in China? Yes, they do, just like they do everywhere else when demand falls, or tastes change, or recession takes out consumer spending.  But doesn't China's domestic market and other export markets make it invulnerable

to a U.S. recession? China expert Andrew J. Nathan doesn't think so. As he writes in the

July/August 2006 issue of Foreign Affairs:

But doesn't China's domestic market and other export markets make it invulnerable

to a U.S. recession? China expert Andrew J. Nathan doesn't think so. As he writes in the

July/August 2006 issue of Foreign Affairs:

Even the most astute analysis of current trends may not accurately predict the future. (CHS--first get the standard-issue pundit caveat out of the way.) Major changes in a society, as China's past amply illustrates, are often disjunctive. And so it is prudent to ask what events could derail whatever process is taking place in China today.As this chart shows, China is not alone in being heavily dependent on exports to the U.S. Indeed, it is difficult to examine this chart and then claim that a global recession is not inevitable as the housing bust ends the equity extraction which has propped up U.S. consumer spending for the past five years. June 27, 2006 Real Estate Bust: The Exhaustion of Debt  Interest rates have yet to peak, but already the buzz is about the Federal Reserve's

next round of "easing." The expectation: lowering interest rates will re-inflate the

housing bubble and thus the economy. Alas, there's a little thing called debt exhaustion

and it does not respond to dropping interest rates.

Interest rates have yet to peak, but already the buzz is about the Federal Reserve's

next round of "easing." The expectation: lowering interest rates will re-inflate the

housing bubble and thus the economy. Alas, there's a little thing called debt exhaustion

and it does not respond to dropping interest rates.

Here's why: as real estate values deflate from bubble heights, owners' ability to borrow more--at any interest rate--is severely impaired. At the same time, the government borrowing which has seemed so "affordable" during boom times now begins feeding on itself, requiring unending, massive borrowing just to pay the interest on the vast sums borrowed during "good times." While it is at best specious--if not perilous--to draw too many parallels between Japan and the U.S., it is instructive to look at what happened to Japan after its property bubble burst in 1990, and to consider if there's anything we can learn from their 15 years of decline and loss.  Exhibit 1 is their skyhigh public borrowing. The first chart shows that servicing

the public debt (government bonds) requires an astounding 70% of tax revenues. (This

includes the interest, overhead and bond redemptions.)

Exhibit 1 is their skyhigh public borrowing. The first chart shows that servicing

the public debt (government bonds) requires an astounding 70% of tax revenues. (This

includes the interest, overhead and bond redemptions.)

The second chart shows the debt of various developed nations as a percentage of their GDP. Japan's hovers at an unprecedented 150% of GDP. The U.S. number of about 70% looks relatively benign, but the numbers are staggering nonetheless. The U.S. paid $240 billion in interest on the national debt in this fiscal year--an expense so large that it is exceeded only by national defense, Social Security and Medicare. Not only that, but it has risen sharply from the $208 billion paid in 2005--as the debt itself grows by $250 billion per year and as interest rates rise. Here is where the stories diverge. While Japan is famously a nation of savers--and also as a nation in which savers have few options other than putting their money in low-yield government bonds or certificates of deposit (CDs)--we of course are famously profligate, a nation with negative savings. What does this mean? It means the Japanese self-funded their immense government borrowing--in other words, they saved the money and lent it to their government to fund deficit spending. Here in the U.S., we save nothing so the deficit is borrowed from foreigners.  The other difference is inflation. While Japan labored under deflation--prices for

both assets and goods dropped, year after year, making the huge debts even harder to pay down--

in the U.S. inflation is rising, regardless of what the official statistics indicate. That

means interest rates must rise, making it increasingly expensive to service debt (pay interest

on outstanding debt).

The other difference is inflation. While Japan labored under deflation--prices for

both assets and goods dropped, year after year, making the huge debts even harder to pay down--

in the U.S. inflation is rising, regardless of what the official statistics indicate. That

means interest rates must rise, making it increasingly expensive to service debt (pay interest

on outstanding debt).

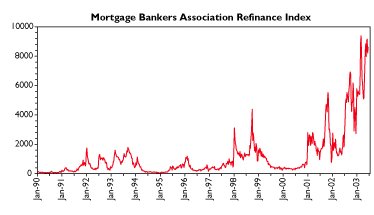

Here's how it works at the homeowner level. Homeowners have already indebted themselves

to very near the maximum. How do we know this? Because withdrawal of equity via re-financing

has withered. Why? As the value of housing declines, the ability to withdraw more equity

disappears. Not only that, but middle-class households have borrowed all that their

incomes (which have been flat for years) will allow.

Here's how it works at the homeowner level. Homeowners have already indebted themselves

to very near the maximum. How do we know this? Because withdrawal of equity via re-financing

has withered. Why? As the value of housing declines, the ability to withdraw more equity

disappears. Not only that, but middle-class households have borrowed all that their

incomes (which have been flat for years) will allow.

Even if interest rates drop back, fully-indebted households have neither the rising assets nor rising income to support more debt--at any price. This is debt exhaustion. Even if the Fed lowered short-term interest rates back to 1%, rising inflation guarantees that long-term rates (mortgage rates) will continue to edge higher as foreigners demand a yield at least equal to inflation.  Japan is also instructive in another way. As property values plummeted from the bubble

excesses, so too did the Japanese stock market. With all that equity and borrowing suddenly

removed from the system, there was less money to support stock prices and company profits.

Japan is also instructive in another way. As property values plummeted from the bubble

excesses, so too did the Japanese stock market. With all that equity and borrowing suddenly

removed from the system, there was less money to support stock prices and company profits.

As the chart above reveals, total household wealth is doubly vulnerable--a decline in real estate wealth will be followed by a decline in stock market wealth as the economy slides into recession. So regardless of what the Fed does, the real estate bubble cannot be re-inflated, nor can strapped households borrow more to spend spend spend in the bubble-supported consumer paradise known as the U.S. economy. This is debt exhaustion. And as tax revenues shrink in the recession, then a growing slice of whatever tax revenues remain must be spent to pay the rising interest on the government's still-growing debt, bleeding money from other government programs and from the government payrolls. It is a classic "double-whammy," and it will not vanish if short-term interest rates drop a point or two. Japan is a cautionary tale. Once housing equity dries up, households can no longer borrow more, even if interest rates drop to near zero. And even if interest rates fall, the government must borrow more to offset recession-ravaged tax revenues, creating a cycle of ever-rising debt and interest payments. Three readers correctly identified last week's Friday Quiz site as Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park, Big Sur, California. A collector's copy of my little novel I-State Lines goes to the first winner. It's a wonderful place and well worth a visit if you happen to be near this section of the Left Coast. June 26, 2006 Science Matters: ABM I have been planning to launch an occasional series called Science Matters on topics in which some very basic science can cut through the welter of uninformed opinion which clutters both Big Media and the Web. Today is the first entry. Armed with only high school chemistry and physics and a B.A. in liberal arts, my hope is to leverage a typically non-expert perspective into some fresh understanding of complex subjects. Our first topic: Missile Defense  Wait--don't click to the next blog just yet. This is interesting stuff. Whatever

your political persuasion, hopefully you recognize the threat posed by rogue states ruled

by fanatics who view the death of thousands as a glorious spiritual victory

(Iran) or callous madmen who are capable of launching nuclear weapons as part of a political

calculation of survival (North Korea).

Wait--don't click to the next blog just yet. This is interesting stuff. Whatever

your political persuasion, hopefully you recognize the threat posed by rogue states ruled

by fanatics who view the death of thousands as a glorious spiritual victory

(Iran) or callous madmen who are capable of launching nuclear weapons as part of a political

calculation of survival (North Korea).

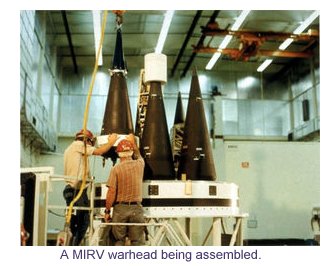

There is merit in at least examining anti-missile defense options. Let's start by de-politicizing the issue. Some feel having a defense will trigger an arms race (as if we're not already in multiple arms races anyway) while others feel no cost is too great to protect American cities from a potential catastrophe. The issue boils down to this: can such a system actually work in a shooting war, and can we afford it? First, a bit of background. Anti-missile systems have been in the research- and-development process for decades. The idea is an obvious offshoot of anti-aircraft missiles: if we can shoot down an enemy airplane, why not speed things up and shoot down a ballistic missile? Here are the problems. The first is speed, of course--ballistic missiles are traveling at very high speeds as they descend from the height of 1,000 miles: about five miles per second. Second, they are rather small targets. Hitting a city or a ship is easier than hitting a long, thin cylindrical object, and once the rocket body has been expended, all that's left is the warhead, which is not much larger than a car. (see photo below)  Third, there are cheap and easy ways to confuse any anti-missile defense. The warhead

can separate in space into multiple warheads (called MIRV, multiple independently targetable

re-entry vehicle), and various decoy warheads can be dispersed as well.

These factors make locating and tracking the target difficult. This is called "target

acquisition." Trying to intercept a small, very fast-moving target is often summarized as

"hitting a bullet with a bullet."

Third, there are cheap and easy ways to confuse any anti-missile defense. The warhead

can separate in space into multiple warheads (called MIRV, multiple independently targetable

re-entry vehicle), and various decoy warheads can be dispersed as well.

These factors make locating and tracking the target difficult. This is called "target

acquisition." Trying to intercept a small, very fast-moving target is often summarized as

"hitting a bullet with a bullet."

In the Reagan-era "Star Wars" missile defense scheme, this problem would be saolved by deploying space-based lasers. Five miles per second is pretty pokey compared to light's 186,000 miles per second, and so the advantage of a laser positioned above the turbulance of the atmosphere looked like a solution. Alas, there are problems with lasers. The first is that such a laser would have to be extremely powerful. Where are you going to get a power source large enough to fire such a laser? (An extension cord to space would be very very expensive and very very thick.) About the only practical way to generate such high bursts of power is a chemical laser, which can only be fired once, or at best, at intervals. And then you have the problem of such a system sitting for years in the deep freeze of space, waiting for the moment when it must work flawlessly. A friend with a physics degree and a working knowledge of lasers pointed out a simple way to counter such a laser: put the missile into a fast spin. Lasers do need some time to damage the skin of the re-entry vehicle/warhead, and a spinning warhead would diffuse the laser's concentrated light. You might peel off some of the skin or etch the surface, but the laser would constantly be hitting a new section of the spinning warhead. For these reasons, space-based lasers are impractical (not to mention horrendously costly and of unknown reliability.) The physics of missile launch define its vulerability: a missile is vulnerable when it is large, slow and emitting a huge hot plume of heat which can easily be tracked--that is, right after it has been launched, in the so-called "boost phase." The physics of rocketry also limit how fast the rocket can reach high speed (the faster you accelerate, the more fuel you use, making your rocket bigger and heavier in the process, which requires even more fuel, etc.) To cut to the chase: any ballistic rocket is a big, fat, hot, easy to track sitting duck in the first moments after launch. Nice, you say, but the bad guys are over there and we're over here. How do we nail their missile in the first few moments of flight? The answer is geography: the planet is mostly ocean. And the U.S. has the world's largest blue-water (ocean-going) Navy. Pretty much the only terrestrial launch sites which couldn't be reached by a sea-launched anti-missile missile are the interiors of Russia and China, and we have to assume the leaders of those nations have little motivation to engage in a mutually unwinnable nuclear war with the U.S. OK, but do we have ship-launched missiles which can actually hit ballistic missiles in the boost phase? Answer: we do. The key to affordable high-tech weapons is to use existing ships ("platforms") and existing missiles. And since the Navy has been working for decades to provide anti-missile defense for its large capital ships, it already has such a system in place: the Aegis Cruisers, which were designed to track, acquire and destroy the small, fast anti-ship missiles of the sort which almost sank the U.S.S. Stark some years back. (The Stark was a small ship without any anti-ship missile defense. The fleet has 69 Aegis Cruisers.) Can such anti-ship technology be expanded into a ballistic missile defense? The answer appears to be at least a qualified yes. Tests of such a sea-launched anti-ballistic missile (ABM) missile in 2003 and 2005 were successful. Inter-service rivalry is a reality that must be dealt with politically. The Air Force, rather naturally, is very keen on using aircraft to shoot down ballistic missiles in the boost phase, and the Army sees an acute need to keep improving the land-based Patriot missile defense which saw action in the first Gulf War. While these systems may well have a part, when it comes to defending the nation against rogue-state missiles, it's very clear: only ships can be kept nearby indefinitely, and only ship-based systems are capable of detecting the launch and firing the anti-missile missile in time to catch the rogue-state missile in its early boost phase. The tests of the system referenced above took about 4 minutes from the launch of the target missile (the bad guy's missile) to its destruction. What about cost? In that the Aegis radars, launchers, ships and missiles are already in service, the cost of upgrading to ballistic missile defense is on the order of $300-400 million (at least initially), as opposed to $60 billion or even higher for some space-based system (clearly unaffordable, never mind the technical objections). The argument against sea-based ABM boils down to this: all the enemy has to do is sink the Aegis cruiser, and then they're home free. Yes, but easier said than done. Recall that the Aegis' entire purpose is anti-ship defense; firing a couple of cheap anti-ship missiles at an Aegis may not work as advertised. As for submarines--rogue states don't have submarines, and in any event the U.S. maintains a robust anti-submarine defense. getting close enough to an Aegis battle group to launch a torpedo will not be that easy. Possible, no doubt, but certainly not easy or guaranteed. Most obviously: do ya reckon firing on a U.S. Navy ship is an act of war which will draw a response? Trying to sink an Aegis cruiser would certainly alert the U.S. that someone was planning/hoping to launch a ballistic missile. But just trying to sink the ship would be a declaration of war. And the ships have multiple layers of anti-missile defense, so a "just sink the Aegis" plan might fail. If you don't have a "Plan B," then that is a very high-risk gamble. And convincing potential enemies that the gamble isn't worth taking is the entire point of a working ballistic missile defense. Here are some interesting articles for further reading: A good overview of missile defense by Gen Charles A. Horner, USAF (Ret.) ship-based ballistic missisle defense A White Paper on the Defense Against Ballistic Missiles June 22 & 23, 2006 My Brand Management Stinks  One of the hottest trends in business management circles is "brand management."

Now that my modest little blog is attracting 30,000 unique visitors a month, I reckoned I

needed some brand management pixie dust.

One of the hottest trends in business management circles is "brand management."

Now that my modest little blog is attracting 30,000 unique visitors a month, I reckoned I

needed some brand management pixie dust.

So I hired management consulting gurus NAND Corporation, based in Santa Monica, Calif., my birthplace. (Yes, they do keep surfboards in the lobby so the highly paid gurus can catch a wave and be sittin' on top of the world during breaks.) The wizards at NAND were rather harsh in their assessment of my current aimless brand. They said my topic selection was all over the map, from a Friday quiz for readers to movie reviews to macro-economic analysis to sophomoric, hokey ad parodies. They recommended tightening my focus onto a lucrative subfield of Blogland: "innovation transformation." Once I carved out a niche in the hot field of fostering, provoking and engineering innovation, I could count on my site becoming a "must see" site for CEOs--and be able to sell ads to Google, Yahoo and a host of other advertising giants. They provided me with an example of the kind of entry I would need to start writing that set my mind reeling: The ethnography of the cosmopolitan is the new core competence ... as offshore outsourcing moves to a greater focus on skill building arbitrage, we see a shift to "fifth generation" outsourcing... Trendalyzer is the essential new software package for benchmarking metrics in innovation....  Rather than write tripe like that and sell ads which annoy readers, I've decided to

annoy readers myself by keeping the all-over-the-map "unfocus" of the current site.

Rather than write tripe like that and sell ads which annoy readers, I've decided to

annoy readers myself by keeping the all-over-the-map "unfocus" of the current site.

So my brand is no brand: a generally annoying mix of an annoyingly wide range of topics, unfettered by outside ads. I know you all miss having banner ads, click-through links and all the other fun stuff that makes ad-choked sites the darlings of the Internet, but it's part of my "no-brand" "unfocus" to avoid brands--unless they're paying me huge bucks on deep background.  Instead of selling irritating ads, I've aggressively pursued some new

"deep background" sponsors for the site.

Instead of selling irritating ads, I've aggressively pursued some new

"deep background" sponsors for the site.

Everyone knows that I pocket a hefty fee monthly for pitching Kroika! Cookies from time to time (please see the links on the left under "Kroika! Chronicles"), and based on the singular success of that partnership I've added Jank Coffee (I did some design work for them in the past), and Cervantes Beer, home of the visually witty "Pancho and the Windmill" ad campaign. As for Astra Zastra, whose ears I've pinned several times here regarding their massive ad campaigns to sell side-effect-riddled drugs (Zombiestra) for made-up diseases (Quatro-Polar Disorder)--well, the folks over at AZ made me an offer I couldn't quite refuse, and no, it wasn't a free supply of Zombiestra.  Of course the deal is the same

I have with Kroika: by trashing the company and its products, just as I've always

done, then my site retains that magic credibility which their ads can never attain.

Of course the deal is the same

I have with Kroika: by trashing the company and its products, just as I've always

done, then my site retains that magic credibility which their ads can never attain.

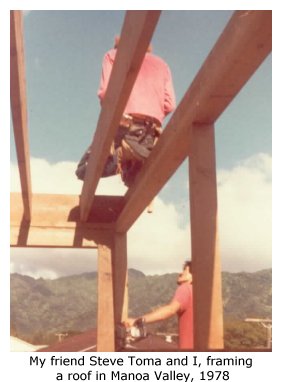

It's ironic, isn't it, getting paid to do what I already do--mock worthless ad campaigns and consumer products. Somehow the corporate handlers figure that the mention on a credible site more than offsets the mocking--go figure. I am just a dumb writer, so what do I know? Please welcome this site's new corporate sponsors: Jank Coffee, Cervantes Beer, and Astra Zastra Pharmaceuticals. I promise their huge fees to me and occasional appearance as objects of derision will be lost in the "no brand" mix of unfocused stuff which is, sadly, my brand. NOTE: As I will be "away from my desk" through Sunday, here is the Friday "where is this?" Quiz somewhat in advance of Friday. There will be no Saturday entry.  Friendship gets short shrift in our culture. Yes, friendship does make brief

appearances in popular culture, but only as a precursor to romance, or as an obstacle to romance which is

overcome in some comedic fashion.

Friendship gets short shrift in our culture. Yes, friendship does make brief

appearances in popular culture, but only as a precursor to romance, or as an obstacle to romance which is

overcome in some comedic fashion.

But friendship takes romance any day. Friends are who you turn to when romance sours, as the two young guys in my little novel I-State Lines find when each of their romantic dreams dissolves into a painfully transparent cloud of dust. Friends are who find you jobs (as Daz does for Alex and himself), and they're who you can travel with without killing each other (although you may get close). And friendship between guys and gals is a beautiful thing. It isn't vulnerable to the vissitudes of romance, and it works on the magic similarities and differences between the sexes. All those romantic comedies got it wrong: it's when there is no promise (or dread) of romance that friendships between guys and gals can truly blossom into lifetime bonds. OK, here's the part where I pitch my little novel and you wander off to read something else: You can order my little novel from my favorite online independent bookstore, The Kaleidoscope: Our Focus Is You . Or if you have an open order at amazon.com, you can of course add I-State Lines Be the first to identify the specific locale behind me and my beautiful friend, and I'll send you a collector's copy of my book I-State Lines. (Hint: that waterfall falls directly onto an inaccessible Pacific coast beach.) So email me! June 21, 2006 Who Gets Hammered in the 2007 Housing Bust: the Lower Middle Class  A great con has been played on the most vulnerable aspirants to the American Dream--those

striving mightliy to join the middle class. Just buy a house, the doctrinaire pitch

has it, and soon, thanks to rising housing prices, you'll have equity and thus some

measure of wealth. After all, house values never drop, they only rise.

A great con has been played on the most vulnerable aspirants to the American Dream--those

striving mightliy to join the middle class. Just buy a house, the doctrinaire pitch

has it, and soon, thanks to rising housing prices, you'll have equity and thus some

measure of wealth. After all, house values never drop, they only rise.

Only there was one little problem: millions of households didn't have the traditional 20% down payment--a standard which became ever more unattainable as housing prices exploded. The wonderful folks in the mortgage lending industry, with help behind the curtains from Federal regulators, came up with a solution: an exotic stew of hybrid mortgages, mortgages which required no down payment, and indeed, no payments of principal. Virtually everyone who wasn't in prison and who had a job above minimum wage could now buy into the American Dream.  But as I have detailed here (Foreclosures:

How Bad Will It Get?), these late-comers to the great "join the middle class through

homeownership" party will most likely lose their tenuous hold on their houses.

(Also see (Foreclosures Part II.)

But as I have detailed here (Foreclosures:

How Bad Will It Get?), these late-comers to the great "join the middle class through

homeownership" party will most likely lose their tenuous hold on their houses.

(Also see (Foreclosures Part II.)

But hasn't the great housing boom fueled a heady rise in home equity, lifting all boats? Apparently not. This chart reveals that homeowner equity has dropped even as housing prices rose. Wait a minute; housing prices have certainly risen, so where's the equity? We all know the answer: it's been borrowed and spent.  As this chart demonstrates, the extraction of home equity--some $4 trillion by most accounts--has

been spectacularly unprecedented. Clearly, this is not confined to the bottom 5% of

homeowning households; those poor souls barely enjoyed the heady rise in equity before it

started falling.

As this chart demonstrates, the extraction of home equity--some $4 trillion by most accounts--has

been spectacularly unprecedented. Clearly, this is not confined to the bottom 5% of

homeowning households; those poor souls barely enjoyed the heady rise in equity before it

started falling.

So who extracted $4 trillion in equity? The great middle class, of course. The equity was especially tempting to the lower middle class--the folks who are being squeezed by flat wages and rising inflation. As this chart shows, American homeowners are no longer sitting on paid-in-full homes; they're sitting on heavily leveraged mortgages they've taken out. And a significant percentage of those mortgages are now adjustable, meaning they will re-set to higher rates over the next few years: Adjustable-rate mortgages now account for a quarter of the more than $8.5 trillion in outstanding loans, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association of America. "We're talking about potentially 2 to 3 trillion dollars of mortgages being these adjustable rates that are going to come due to reset in the next 18 to 24 months," said Rick Sharga, vice president of RealtyTrac Inc., a database on foreclosure properties.  The housing cheerleaders like to spout numbers which mask the enormity of this

leveraged debt; for example, "only 4% of mortgages will re-set to higher rates in 2006."

But the problem isn't just with these marginalized borrowers; it's with everyone who

borrowed heavily against their equity in lieu of savings.

The housing cheerleaders like to spout numbers which mask the enormity of this

leveraged debt; for example, "only 4% of mortgages will re-set to higher rates in 2006."

But the problem isn't just with these marginalized borrowers; it's with everyone who

borrowed heavily against their equity in lieu of savings.

The central conceit at the heart of the housing cheerleaders' rosy view is exceedingly heartless: yes, a bunch of people will lose their homes, but they couldn't afford them anyway. But the problems of "the little people," the cheerleaders say, won't affect all of us solid middle-class homeowners who bought long ago; we're safely sitting on tons of equity.  Really? Then why has home equity been shrinking for years? (see chart above) The reason

is obvious: American households have indulged in a borrowing spree without precedent.

Really? Then why has home equity been shrinking for years? (see chart above) The reason

is obvious: American households have indulged in a borrowing spree without precedent.

This quasi-rosy view--sure, some households will get hammered by the recession, but the "rest of us" will be unaffected--is encapsulated in this report from the FDIC which predicted the recession would take down the 10% of U.S. households who are overleveraged: Scenarios for the Next U.S. Recession. The cheerleaders are missing one key point. The collapse of the housing bubble won't just take out an isolated 10% of households; it will take them out first and then move down the economic chain in domino-like fashion. Sure, it will be the maid and her mechanic husband who lose their home first, but then the carpenter and the mortgage broker will lose their jobs, and some of them will lose their homes, too. As the capital gains and transfer tax revenues dry up, then the municpalities which have been counting on that revenue to make payroll will have to slash heretofore sacrosanct government positions.  The dominoes don't stop there, of course; as housing prices fall under the weight of

foreclosures and fire sales by desperate "investors," those middle-class households who

thought they were safe leveraging "only" 80% of the value of their home will wake up and find

a 20% decline in home values has wiped out their equity. Now, when they have to sell, due

to the usual litany of life's woes--job transfers, divorce, medical emergencies, etc., they

will discover they have negative equity: their mortgage is larger than the value of their house.

The dominoes don't stop there, of course; as housing prices fall under the weight of

foreclosures and fire sales by desperate "investors," those middle-class households who

thought they were safe leveraging "only" 80% of the value of their home will wake up and find

a 20% decline in home values has wiped out their equity. Now, when they have to sell, due

to the usual litany of life's woes--job transfers, divorce, medical emergencies, etc., they

will discover they have negative equity: their mortgage is larger than the value of their house.

As this chart shows, traditional savings has fallen to a negative number. People have been perceiving their equity as "savings," and have "taken off some of the cream" as their "savings/equity" has risen by leaps and bounds. Now that their "savings account/equity" has started to decline, withdrawals are no longer possible for those who have already extracted most of their equity via re-finances and lines of credit. As I highlighted yesterday, it isn't the top 10% of households who will suffer in the 2007 housing bust recession. They control over 2/3 of the private wealth of the nation (see below for the link to a Wall Street Journal story.) No, it's the 50% of households whose share of national wealth is a meager 2.5%. That 50% comes to about 150 million people. You do see where this is going, don't you? A political revolution is brewing. Not a violent revolution, of course, but one fueled by the catastrophic loss not just of whatever small capital those 150 million people (half of our nation's population of 300 million) might have acquired, but more importantly, perhaps, the loss of their belief in the American Dream--of home ownership and a life of luxury paid for by painless extraction of ever-rising equity. Whether you like it or not, or if it fits your ideological bias, the truth is: there is an "us" and "them" in America. As The Economist pointed out in The Rich, the Poor, and the Growing Gap Between Them, income disparity is larger in the U.S. than in any other industrialized nation. Meanwhile the cheerleaders write tripe like this: Why The Slowdown Won't Become A Slump. The cheerleaders always make one key assumption: the poor dumb lower-middle class (what we used to call the working class) folks can lose their homes and livelihoods, but "we" will be protected by our fat equity and our plush middle-class jobs. Well, don't count on it, buster. The equity slide has a long way to go, and every 10% down will take more "middle class" households' wealth with it. And don't be so sure your job is safe; when the 10% of the workforce which depends on housing gets decimated, don't you think there will be an effect on retail, banking, restaurants, government, and indeed, on every sector of the economy? By December 2007, the cheerleaders' pom-poms will be bedraggled, and their rahs-rahs dispirited as the ugly specter of class warfare darkens their perpetually rosy view of leverage, debt and financial disparity. 30 million Americans, those in the top 10%, will be cushioned by their 2/3 share of the $50 trillion in total U.S. household assets; 150 million will have no assets, only debts, and the 120 million in between will be watching their share of the pie dwindle as housing values notch ever downward and unemployment notches ever upward. A recipe for rosiness? I think not. June 20, 2006 What We Know, What We Can Safely Predict Will interest rates rise? Will the economy slip into stagflation (stagnation + inflation)? Will the housing, stock and commodity markets all recover and start heading higher? Will the dollar plummet 40%, as many predict?  A good place to start our analysis of these questions is to sort out what we already know

and then build our expectations/predictions on that foundation.

Here's what we already know about the U.S. and global economy:

A good place to start our analysis of these questions is to sort out what we already know

and then build our expectations/predictions on that foundation.

Here's what we already know about the U.S. and global economy:

Furthermore, one of the fastest-rising drivers of inflation--medical expenses--is rapidly being shifted from employers to their middle-class employees via larger co-payments and deductibles. If the great middle class doesn't notice inflation now, they will certainly notice it when their employer starts making them pay part of the nation's skyrocketing healthcare costs.  The standard assumption on energy is that it takes a year or two for increases to work their way

into prices--and here we are, two years from the start of significant jumps in energy costs.

And voila, the Fed is suddenly noticing some inflation it can't quite massage away.

Coincidence? Hardly.

The standard assumption on energy is that it takes a year or two for increases to work their way

into prices--and here we are, two years from the start of significant jumps in energy costs.

And voila, the Fed is suddenly noticing some inflation it can't quite massage away.

Coincidence? Hardly.

Anyone in business knows inflation is galloping ahead far faster than the government's meager 2.5% "core rate." The list of expenses which have leaped by double digits is long and growing: property taxes (ignored by the CPI); medical (relegated to a tiny percentage of the CPI despite being 15% of the total U.S. GDP), education, shipping, natural gas--exactly how can all these major household expenses be rising by 10% or more and inflation remain 2%? We know the answer: "owners equivalent rents," which make up about a third of the CPI, have been dropping for years. Now as housing cools they've stopped dropping and have started rising, albeit modestly. Without that massively deflationary statistic erasing true inflation, now the inflationary chickens are finally coming home to roost. China, long the source of deflationary low wages, is now experiencing rapid increases in wages as well as huge run-ups in the prices of commodities such as nickel, copper, steel, oil and cement--not to mention higher shipping costs to bring all those heavy raw materials to China via the sea. The era of ever-cheaper prices for goods from China is over; costs for goods made in Asia will rise unless currencies re-adjust (which they won't, but that's another story: exactly why would China and Japan allow their currencies to bolt 40% higher against the dollar, destroying their farming sector and export business in one fell swoop?)

At the same time, (as I have described in recent posts) lending standards are slowly being tightened by Federal regulators. ( From the Wall Street Journal: Housing Banks May Be Forced To Cut Dividends.) Nationally, real-estate-related industries accounted for 74 percent of new jobs over the past five years. At the end of 2005, 11 percent of Washington area jobs were held by real estate brokers, construction workers, mortgage brokers or otherwise tied to real estate, according to an analysis of Labor Department data by Moody's Economy.com. That's the highest level in the 35 years the data go back.  The tiresomely repetitive financial cheerleaders point to charts like this to support

their rah-rah thesis that households are wealthy and can handle more debt. Home equity

is rising! Stock portfolios are rising! Everyone's richer every year!

The tiresomely repetitive financial cheerleaders point to charts like this to support

their rah-rah thesis that households are wealthy and can handle more debt. Home equity

is rising! Stock portfolios are rising! Everyone's richer every year!

Nice, but they forgot to mention that most of that equity and securities wealth is concentrated in the top 10% of households. But let's let the Wall Street Journal carry this ball: Wealthiest American Families Add To Their Share of U.S. Net Worth: The top 1% held 33.4% of the nation's net worth in 2004, up from 32.7% in 2001, but still lower than a peak of 34.6% in 1995. In 2004, the wealthiest 1% percent owned 70% of bonds, 51% of stocks and 62.3% of business assets.  They also forgot to mention that most households are dependent on housing values rising

ever higher. If housing merely stops rising, never mind actually drops, then the

borrowing power and net worth of most Americans (other than the golden 1% who own 70% of the bonds

and half the stocks) will skid to a screeching halt.

They also forgot to mention that most households are dependent on housing values rising

ever higher. If housing merely stops rising, never mind actually drops, then the

borrowing power and net worth of most Americans (other than the golden 1% who own 70% of the bonds

and half the stocks) will skid to a screeching halt.

This chart reveals the absolute dependency of the U.S. economy on the recent (and sadly transitory) rise in housing wealth.  If nobody steps up to pay $100 billion every few weeks for a measly 5% return, then the government must

raise the interest rate it is offering buyers. Now if potential buyers keep reading that

the dollar is going to plummet 40% and that Warren Buffett has bet big against the dollar,

do you reckon that increases their desire to buy a bond which pays a miserable 5%? Why would

it?

If nobody steps up to pay $100 billion every few weeks for a measly 5% return, then the government must

raise the interest rate it is offering buyers. Now if potential buyers keep reading that

the dollar is going to plummet 40% and that Warren Buffett has bet big against the dollar,

do you reckon that increases their desire to buy a bond which pays a miserable 5%? Why would

it?

So listen up, people; the Fed could frantically drop short-term rates in a pathetic and misguided attempt to reinflate the housing bubble--and mortgage rates could rise dramatically if bond buyers (mostly foreign banks) decide not to risk a dollar drop. As this chart shows, bond yields tend to run in cycles of about 20 years. Clearly, the bottom is in and rates will rise--perhaps for as long as the next 20 years. To recap: this is what we know: Do you bet that inflation is benign and will fall? Do you want to bet that bond yields and therefore interest rates will fall? Do you bet the U.S. economy will prosper even as its primary prop, housing, rolls over? If so, you have to ask yourself: Why? June 19, 2006 The Three Secrets to Unloading Property Today  I happened to be driving behind a "bubblemobile"

I happened to be driving behind a "bubblemobile" (truck filled with dozens of shiny new "for sale" signs) when a flyer blew out of the truck bed and miraculously swept into the interior of my car. The flyer read: NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION--DO NOT EMAIL OR TRANSMIT ELECTRONICALLYThere were no identifying names or addresses on the paper, and the truck was similarly unmarked. The truck exited, and I thought about following it, but what was the point? I think the operative expression is, once again, plausible deniability. DISCLAIMER: this entry is a work of satirical fiction. It bears no resemblance to any person, publication, market, philosophy, or indeed, to anything real in the known Universe. It is not intended as advice, implied or otherwise, in any matter, especially the sale of property or any security or indeed, any good or service in the known Universe or beyond; it is intended solely as a mild form of amusement. No warranty is present, either stated or implied, that this entry will actually be amusing to readers, especially those with a financial stake in the continuation or expansion (if that were even possible) of the housing bubble. * * * We have a winner! Two readers correctly identified Friday's mystery location as Mesa Verde National Monument in Colorado. A signed collector's copy of my novel I-State Lines goes to the first person with the correct answer. Thank you to everyone who sent in a guess. June 17, 2006 Lifespans  Humans are to tortoises as dogs and cats are to humans. Those of us of a certain age

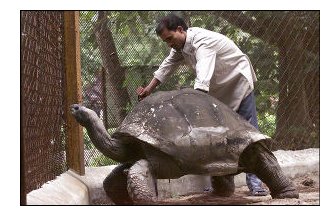

(such a polite way to say "geezer") are amazed almost daily by how quickly our lives fly

by, and saddened by the loss of those from our past who have passed away. How wondrous, then,

to consider a creature (endangered, naturally) whose lifespan places us humans in the same

paltry position as our pets: a lifespan only a third of a longer-lived and dearly loved companion.

Humans are to tortoises as dogs and cats are to humans. Those of us of a certain age

(such a polite way to say "geezer") are amazed almost daily by how quickly our lives fly

by, and saddened by the loss of those from our past who have passed away. How wondrous, then,

to consider a creature (endangered, naturally) whose lifespan places us humans in the same

paltry position as our pets: a lifespan only a third of a longer-lived and dearly loved companion.

Here are the stories of two such creatures, tortoises who lived in the time of Captain Cook and Darwin. Creatures who may well remember their first, second, third, fourth and fifth human keepers affectionately, much as we remember our long-lost pets. Here is a selection from a Wikipedia entry: Tortoises generally have lifespans comparable with those of human beings, and some individuals are known to have lived longer than 150 years. Because of this, they symbolize longevity in some cultures, such as China. The oldest tortoise ever recorded, indeed the oldest individual animal ever recorded, was Tui Malila, who was presented to the Tongan royal family by the British explorer Captain Cook, in either 1773 or 1777 (the exact date is not known). Tui Malila remained in the care of the Tongan royal family until its death by natural causes on May 19, 1965. This means that upon its death, Tui Malila was at least either 188 or 192 years old, but either figure gains it the title of oldest Cheloniinae (tortoise or turtle) ever recorded.Its research shows that nine of the previous 12 drops in spending on residential housing were followed by recessions, and the latest report forecasts a decline in spending ahead. June 12, 2006 A Drug Industry Running Amok  Astute reader Richard C. responded to my pharmaceutical spoof (Zombiestra) with

this question: "Guess which drug was the most heavily advertised in 2000?

Astute reader Richard C. responded to my pharmaceutical spoof (Zombiestra) with

this question: "Guess which drug was the most heavily advertised in 2000?

Hint 1: The patients would have been far better off spending their money on Pepsi or Budweiser, not to mention a Dell computer. Hint2: The drug had the all too frequent side effect of death." I guessed Viagra (some people have been rumored to die while enjoying the drug's effects) but Richard reports that the answer is Merck's recently withdrawn Vioxx, with a stunning ad/promotion budget of $160 million. To place pharma industry ad spending in context, Richard supplied the following quote: Pharmaceutical companies spent $2.5 billion in 2000 on mass media ads for prescription drugs. What part of overall advertising spending is that? A small portion. U.S. companies spent $101.6 billion advertising consumer products in the “mainstream” U.S. mass media in 2000. That includes internet ad spending of $2.9 billion. Thus, DTC prescription drugs ads represent 2.5% of overall mass media ad spending.I am sure the numbers for 2005 far exceed those for 2000.  The reality of "the drug trade's" profiteering can be seen in these charts of

pharmaceutical spending in the California Workers Compensation program:

The Cost of Pharmaceuticals in Workers’ Compensation.

As the cost of drugs has tripled in just 10 years , one wonders if this massive increase in

spending has improved the health of the recipients--or just the health of the industry's bottom line.

The second chart shows the state's estimate of "excess cost"--i.e. the drug industry's

rip-off of the Workers Compensation system ($112 million in 2005 alone). This is, of course, a relatively small piece

of the overall healthcare spending in the state. The mind boggles at what the "excess cost"

number would be for the entire nation.

The reality of "the drug trade's" profiteering can be seen in these charts of

pharmaceutical spending in the California Workers Compensation program:

The Cost of Pharmaceuticals in Workers’ Compensation.

As the cost of drugs has tripled in just 10 years , one wonders if this massive increase in

spending has improved the health of the recipients--or just the health of the industry's bottom line.

The second chart shows the state's estimate of "excess cost"--i.e. the drug industry's

rip-off of the Workers Compensation system ($112 million in 2005 alone). This is, of course, a relatively small piece

of the overall healthcare spending in the state. The mind boggles at what the "excess cost"

number would be for the entire nation.

The pharmaceutical industry claims that rip-off prices are necessary to fund horribly costly research and development, but a close analysis of this claim reveals a disturbing reality: all these companies spend far more hyping their drugs than they do researching new ones. For a balanced view, please read What Does R&D Really Cost? which details how some startup companies do in fact spend a vast amount of money getting their drug through safety/efficacy trials. But the "big pharma" companies don't fare as well: The pharmaceutical industry's trade group, Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), has long maintained that developing a single new drug and bringing it to market takes on average 12-15 years and costs $500 million. A new report by Public Citizen, a consumer group founded by Ralph Nader, estimates the pre-tax cost of bringing a new drug to market during the nineties was only about $107M. After taxes, they say, the outlay on research and development (R&D) for each successful drug (which must also cover expenses for unsuccessful candidates) could be as low as $71M. PhRMA immediately responded by quoting new estimates upping their figure to $700M. Here is my personal story on pharmaceutical rip-off pricing. Due to my fair skin and massive sun exposure as a child and youth, my dermatologist prescribes a topical cream, fluorouracil, for me every few years to burn off the solar keratoses (pre-cancerous lesions) which form on sun-damaged skin. Ten years ago, the cost of a tube of this 30-year old medication was $40. It has now skyrocketed to $240 a tube. I repeat: This is for a 30-year old medication. Exactly what R&D costs are being amortized by a six-fold increase in price after 30 years? The answer is obviously none--the medication is long off patent. It's simply a case of the medical establishment not really caring what the cost is as long as insurance pays the tab. As a self-employed person, I pay my own bare-bones insurance (Kaiser Permanente) and all my own drug, dental and eye-care expenses at full retail, i.e. what the insurance carrier pays but the fully insured person never even sees. The annual cost for "full insurance coverage" of all healthcare expenses would eat up most of my total annual after-tax income (self-employed people also have to pay their own Social Security taxes)--and I am hardly alone in not being able to pay for "fully insured healthcare coverage." Some 45 million Americans have zero healthcare coverage, a number which seems to grow at a far faster rate than the overall population. For a deeper exploration of drug costs in a non-U.S. setting (Manitoba, Canada), check out High Cost Users of Pharmaceuticals: Who Are They?. A number of readers correctly identified Friday's mystery location as Joshua Tree National Park in Southern California. (Some previous winners also correctly identified JTNP just for the fun of it). A signed collector's copy of my novel I-State Lines goes to the winner. Thank you to everyone who sent in a guess. June 10, 2006 Iranian Films: The Mirror  First, a word on Iranian politics. My Iranian friends tell me that the current regime makes no bones about their goal when speaking in Farsi: they are playing the West for fools, buying time with phony negotiations in order to get The Bomb, which will give Iran the leverage it needs to become the premier regional player and perhaps the leading light in the Muslim world community. How Persian Shi'ite Iran expects the Sunni Arab world to respond to their nuclear dominance is unclear. But not all Iranian citizens back the regime or their goals; many disagree but are silenced by threats or worse; many others, I am told, support the regime only because they, like most citizens of most nations, have known no other. Rather surprisingly, given the repressive nature of the Iranian theocracy, Iranian films open a window onto Iran which is not entirely positive. For example, consider The Mirror Part of the pleasure of non-blockbuster non-genre films is to watch the movie unfold without the expectations of a plot point at minute 20 and all the other artifices of Hollywood script doctors. Nothing wrong with genre films (romantic comedies, thrillers, mysteries, etc.) but they take us on a route we've already traveled before. Not so this film. Did you ever become lost as a young child? This movie captures that anxiety and the confusion of partially remembered clues in an uncaring, distracted adult world. We feel the girl's worry, and fear for her amidst the traffic and the indifference of the adults. We cheer on the occasional adult who offers to lend a hand, and fall back to worry when the help leads to another blind alley. Much of the film's charm lies in the naturalistic "acting" (or shall we say non-acting?) of the lead character, the adorable little girl, while the unadorned street scenes of Tehran give us a "real life" window into everyday life of the Iranian people: bus drivers changing shifts, an old woman complaiing that her son ignores her, several adults' half-hearted attempts to help the little girl recongize her pathway home, and the constant flow of autos which seem to ignore traffic signals. (The Iranian street police are shown in a positive light; while most of the adults seem indifferent to the child's plight, the policeman does try to help the girl.) Perhaps the girl's unsettled, disjointed journey home is a metaphor for the entire Iranian experience. Given the cultural constraints (many Iranian films focus on children, no doubt partly as a mechanism for bypassing censorship), what better way to illustrate the journey of the Iranian people from the repression of the Shah's reign through the tumult of the Revolution to the discord and disappointment of the present than a child's uncertain, half-remembered search for the way home? Why call a film "The Mirror" unless it mirrors something larger than a little girl's heartstring-tugging journey home? This interpretation is reinforced by the radical break which occurs halfway through the film. I won't spoil the movie by describing this surprise in detail, but the pulling aside of the veil between reality and film has a long history--usually in comedy. Bob Hope's asides to the viewer in his 40s-era comedies no doubt inspired Woody Allen's similar aside in Annie Hall (while waiting in line to see a movie, he turns to "us" and excoriates a blowhard intellectual standing behind him), and Mel Brook literally broke down the wall between movie and "reality" in Blazing Saddles, when his film crew burst through a soundstage wall into a Busby-Berkeley-type musical being filmed next door. The break in The Mirror is more disturbing, for it suggests the artifice of film as a metaphor for an Iran which has lost its way cannot be maintained, that real emotion cannot be constrained by the process of filmmaking. The "mirror" of the title is not only a mirror held up to Iranian society, but to the viewer of the film. Once the suspension of belief which is integral to movies has been torn aside, we enter an entirely new movie, one which challenges our understanding both of film as a medium and of Iranian culture. This film is an experience you won't easily forget. June 9, 2006 Where Is This?  Part of my camping ritual is to snap a photo of the campsite. So here in all

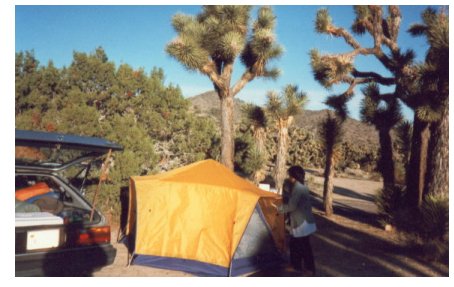

its durable glory is our REI tent (and almost equally durable Honda Accord) sited in a

magnificent desert campground. Any guesses on the identity of the park?

Part of my camping ritual is to snap a photo of the campsite. So here in all

its durable glory is our REI tent (and almost equally durable Honda Accord) sited in a

magnificent desert campground. Any guesses on the identity of the park?

Part of the fun of camping is the camaraderie established by close quarters and thin tent walls. (Note to European tourist playing guitar at midnight by the campfire: could you please practise for your "Bulgarian Idol" audition back home?) Most campgrounds have hosts, volunteers who provide some basic oversight and semi-official presence, and as you might expect, many if not most are very interesting, helpful folks. You meet people camping in a way that you don't staying in resorts, hotels or motels. The two young guys in my little novel I-State Lines meet a retired Marine Colonel while camping, and they visit him at home later in the book. There was a time, back in the Cold War era when the U.S. military was much larger, when practically every guy you met was a veteran; now it's becoming a rarity. That's a loss for the nation, for without this personal understanding, then it's all too easy to slip into a distorted Hollywood view of the military and veterans in general, and to then espouse facile sloganeering in place of an actual understanding of those who are serving in the war. I am troubled that veterans rarely appear in modern fiction (except in military thrillers), and so my book is peopled with vets of all types and ages. This reflects my own experience to be sure, but it also reflects my belief that the service and sacrifice of veterans are as essential to an understanding of our nation as the landscape itself. Camping also enables you to experience Nature in a more intimate light. For instance, you gain a new appreciation for the power of bears when you see an SUV door torn off its hinges, rather like we would open a can of sardines. (That was a pretty expensive Snickers bar you left on the front seat, pal.) Be the first to identify this mystery campground/park, and I'll send you a collector's copy of my book I-State Lines. So email me! Reader JLA correctly identified last Friday's mystery location as Smith Mountain Lake in Virginia. A signed collector's copy of my little novel I-State Lines goes to JLA for the winning answer. Thank you to everyone who sent in a guess. June 8, 2006 Can You Can Tell Which Pill Is Fake?  My source inside global pharmaceutical giant Astra-Zastra tell me that

Chinese-based counterfeiting of the company's new hot-selling drug Zombiestra has

reached epidemic proportions, threatening the firm's sales, reputation and profitability.

My source inside global pharmaceutical giant Astra-Zastra tell me that

Chinese-based counterfeiting of the company's new hot-selling drug Zombiestra has

reached epidemic proportions, threatening the firm's sales, reputation and profitability.

The rep showed me two pills (pictured here) and asked me to select the fake one. They looked identical to me, and I said so. "They are identical," he fumed, "at least on the outside. Inside, the fake is just sugar and cornstarch. These pirated pills are killing us, absolutely killing us." The rep then referred me to some recent media reports which confirmed the dire consequences of massive drug counterfeiting in China: Counterfeiting in China (CNN transcript): MANN: I ask about that because at one point you wrote that in fact some of these drugs are so badly pirated that they could make people sick who think that they are going to benefit.The rep also asked me to read this report: Public Safety Jeopardized by Chinese Counterfeiters, Experts Say; Fake pharmaceuticals contradict notion of "victimless" crime. The problem, the Astra-Zastra source reported, isn't China's copyright and trade-secrets laws per se, but the enforcement of those laws, which is basically zero. He referred to this expert's explanation: MANN: China has been getting a lot of attention, and we've been devoting a lot of attention in this program, to intellectual property theft and copyright piracy. Does China deserve the blame it's getting?The rep complained that they've already closed their primary plant in China because sales had fallen. "People took our erectile dysfunction drug and nothing happened," he said, "because the counterfeit drugs were being wholesaled alongside the legit pills. Since no one could tell the difference, word-of-mouth blamed our product. Our brand's reputation went down the toilet, and so did sales." Even worse, the rep explained, fake Zombiestra pills are entering Canada in huge numbers, where they are passing into the hands of U.S. customers. "People who suffer from quatro-polar disease (please see The New Disease We Just Know You've Got) are actually feeling better taking the pirated pills," he said in great frustration. "They're nothing but sucrose and starch. It's killing our side-effects sales." The rep, who prefers to remain anonymous, leaned forward and spoke in a softer tone. "I don't need to tell you about Zombiestra's side effects, right? Bed-wetting, heart palpitations and road rage. I mean, road rage is getting hot; it's being touted now as the new syndrome, and we're really piling into this new market: road rage is a real disease." "Zombiestra is sort of a loss-leader for us," he explained. "The really big sales are on the follow-throughs, the meds to control the bed-wetting, heart palpitations and the road rage. Now that customers are feeling better on the pirated Zombiestra, and without the side effects, they're not ordering the follow-through meds. It's killing us, I mean really killing us. My commissions are way off, way off." The rep's mood darkened and he fell silent. Then he perked up and said, "but this new road-rage market, it's huge. We're gonna do gangbusters in that one." June 7, 2006 Is Getting Rich Really This Easy?  You know the end of a speculative run is near when major media covers blare "you can't lose."

The latest Barron's cover provides not one but two shining examples of this:

"If Gold Slips to $600, Buy It!" (note the exclamation point) and "Time to Buy Commodities?" (the giddy guy on the

cover who has made a fortune in commodities is your answer: yes, a resounding yes, many times over!)

You know the end of a speculative run is near when major media covers blare "you can't lose."

The latest Barron's cover provides not one but two shining examples of this:

"If Gold Slips to $600, Buy It!" (note the exclamation point) and "Time to Buy Commodities?" (the giddy guy on the

cover who has made a fortune in commodities is your answer: yes, a resounding yes, many times over!)