|

| weblog/wEssays | home | |

|

"Terroir"--California and France (July 10, 2005) "A large part of what we call Nature, is not; it is even quite artificial, lacking both the state and the appearance that it would have in Nature.""Terroir" ("ter-wha" phonetically) is one of those French words dripping with cache (if you know what it means and can actually pronounce it, you're on your way to either being insufferable or actually learning something about wine) that has no analog in English; which is another way of saying that on occasion there is an actual reason to employ it other than snobbery.

Terroir, as you can guess from its obvious similarity to the English "territory" (yes, about a third of the English language has roots in French), is a particular wine-producing area defined by its unique combination of soil and weather. In France, it's a smaller piece of an appellation or region (Champagne, Rhone, etc.). Shops which sell a variety of local products (jams, wine, creme de marron, pate, "agriculture biologique" products, etc.) use "terroir" in their signs, so it also denotes products unique to the local region. If you're being subjected to wine patter by snobs, then the root word may seem to be "terror."

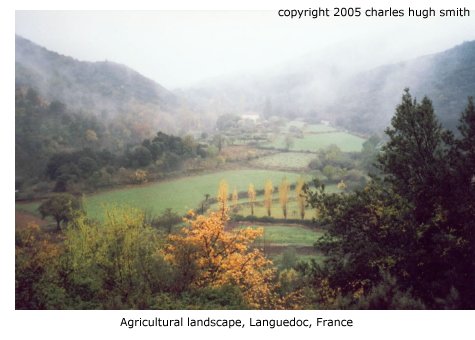

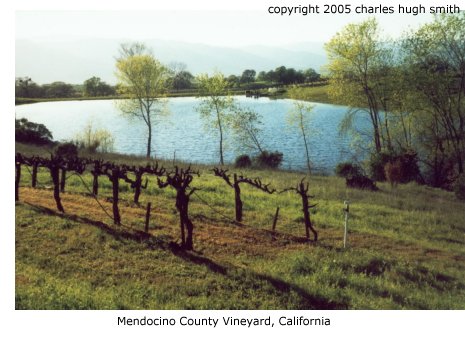

Ironically, perhaps, the people who actually manage the vineyards and make the wine--in other words, the real experts--have in my experience been uniformly down-to-earth. If they use "terroir," it's apologetically, or with an emphasis which communicates their awareness of its frou-frou connotations. But it does have a meaning to them, for it defines and shapes their work. Anyone who's seen the film "Sideways" knows all about pinot noir grapes--remember the rant against merlot?--but if you really want to understand terroir and pinot, make a pilgrimage to the Anderson Valley (route 128) in Mendocino County, California and feel how the weather changes as you approach the Pacific. Grapes grow over vast tracts of California; on a recent drive to Los Angeles, we stopped in Buttonwillow, a fast-food haven in the flat Central Valley just north of the Tehachapi Mountains. To stretch my legs I walked past the truck stop and down a road surrounded by vineyards. In the hazy plains of the great Central Valley, where the weather hardly changes for hundreds of miles, no one talks of terroir. And no doubt the grapes are just as useful as those fawned over in locales far to the north. But terroir has its limits. In Napa Valley, there are many microclimates and soil types; each one defines a terroir-- for example, the Rutherford Dust Society. But what surprises the casual visitor is how many varieties of grapes can be planted within the confines of a 100-acre vineyard. Though the vineyard is within a terroir, there are variations in weather and soil even in such a small parcel. The knowledgeable vitner plants according to the slope, soil depth and type; as a result, one relatively small vineyard (90 acres planted) might have four or even five varietals (for instance, zinfandel, Rhone, petite syrah and grenache), depending on the variety of terrain and soil on the parcel. So if you really want to sound knowledgeable about wine, drop in "deficit irrigation," "fractured shale," "pressure bomb," "fertigation," "subsurface drainage," "dryland farming," or that most feared result of inadequate frost protection, "defoliation." If you can weave these into a conversation, you'll leave the wine poseurs blinking in bafflement. Long before you get to hints of blackberry and chocolate, you have to plant and nurture the vineyard and worry over the moisture content and the berries. But enough about terroir--let's just enjoy the scenery, shall we? * * * copyright © 2005 Charles Hugh Smith. All rights reserved in all media. I would be honored if you linked this wEssay to your site, or printed a copy for your own use. * * * |

||

| weblog/wEssays | home |