| |

Hot Air Dragon: Is China About to Pop?

(July 20, 2006)

First, let's acknowledge--and dismiss--the main subtexts which play out in any

discussion of U.S.-China trade: Many of the

"China is the inevitable superpower of the 21st Century" crowd are, beneath their

cheerleading, deeply anti-American; they hope China replaces the U.S. as the global

superpower not because they are enamoured of China (though they may be) but because

they loathe the policies and indeed, the power, of the U.S. In this they are akin to the Soviet

sympathizers who romanticized life in the Cold War gulag/USSR because they disapproved of U.S. policy

and power.

First, let's acknowledge--and dismiss--the main subtexts which play out in any

discussion of U.S.-China trade: Many of the

"China is the inevitable superpower of the 21st Century" crowd are, beneath their

cheerleading, deeply anti-American; they hope China replaces the U.S. as the global

superpower not because they are enamoured of China (though they may be) but because

they loathe the policies and indeed, the power, of the U.S. In this they are akin to the Soviet

sympathizers who romanticized life in the Cold War gulag/USSR because they disapproved of U.S. policy

and power.

On the other hand, China bashers view everything through the prism of a "clash of

civilizations" in which China is constantly working to weaken U.S. interests in

order to replace the U.S. as the global superpower. Every act is viewed not as China's

understandable impulse to act in its own self-interest, just as the U.S. does, but as

an attack on U.S. interests

I do not ascribe to either of these uninformed, ideologically-driven islands of ignorance.

Yes, China was once a great power (circa 1450 and before), and it may yet become a

global power, but it is not yet a global power and it has many challenges to overcome. Like any

other large nation, it will naturally have some areas of disagreement with the U.S. but

it need not be viewed as an either-or alternative to U.S. power. The Pacific, and indeed, the world,

is big enough for Japan, China, and the U.S. to be large economic and military powers. Yes,

Taiwan provides a dangerous point of friction which could lead to open war, but that scenario

is by no means inevitable.

I do not ascribe to either of these uninformed, ideologically-driven islands of ignorance.

Yes, China was once a great power (circa 1450 and before), and it may yet become a

global power, but it is not yet a global power and it has many challenges to overcome. Like any

other large nation, it will naturally have some areas of disagreement with the U.S. but

it need not be viewed as an either-or alternative to U.S. power. The Pacific, and indeed, the world,

is big enough for Japan, China, and the U.S. to be large economic and military powers. Yes,

Taiwan provides a dangerous point of friction which could lead to open war, but that scenario

is by no means inevitable.

While this either-or choice--"which will be the sole superpower, the U.S. or China?"--appeals

to both ideological extremes, it is deeply false. It is far closer

to the complex, nuanced truth to say that China and the U.S. have become mutually interwined in a vast

commercial and political enterprise. Each now needs the other for its prosperity and to

some degree, political/regional stability.

The big question now is: what happens to Chinese prosperity as the U.S. housing/debt bubble

bursts and the U.S. slides into a deep recession? This question is important

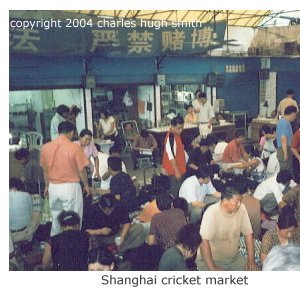

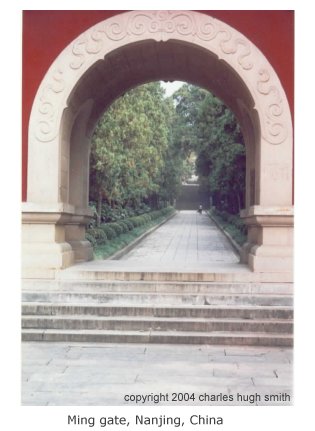

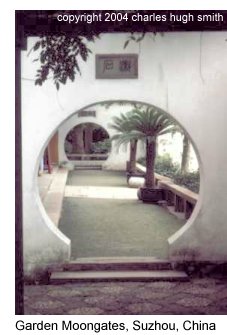

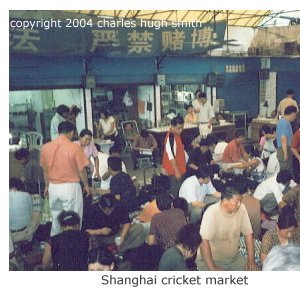

to citizens of both nations, but most especially to the Chinese citizenry. As these photos

demonstrate, I have made several lengthy visits to China; we have many Chinese friends, and

I hope for the security and well-being of all citizens of both the U.S. and China. I do

not see the two as mutually exclusive.

OK, so let's dig in. First up is China's blistering growth:

China reports fastest growth in a decade.

Sounds great, doesn't it? But if we look beneath the surface statistics, there are some

very troubling imbalances. Let's turn to Elaine Kurtenbach's (of the Associated Press) piece

China struggles to tame economy. The presence of a real estate bubble is now

undeniable, as is the astonishing dependence of China on investment for its growth:

Sounds great, doesn't it? But if we look beneath the surface statistics, there are some

very troubling imbalances. Let's turn to Elaine Kurtenbach's (of the Associated Press) piece

China struggles to tame economy. The presence of a real estate bubble is now

undeniable, as is the astonishing dependence of China on investment for its growth:

"Chinese authorities are now scrambling to regain control over a runaway economy," Morgan

Stanley economist Stephen Roach wrote in a recent report. "China needs a more serious

policy tightening."

Construction projects such as the forests of cranes on Changsha's horizon are just the

most visible evidence of a nationwide investment binge that raised new spending on

construction and factory equipment to $318 billion by the end of May, up 30 percent

from the same period of 2005.

Such investments are forecast to exceed $1.3 trillion this year, nearly half of China's GDP.

To finance that spending, China's big commercial banks, their already fat cash balances

swollen by government bailouts and recent multibillion-dollar initial public offerings,

issued new loans worth $267.5 billion in the first half of this year.

The worry is that too much of the money is going into redundant or ultimately unprofitable

investments, risking a rebound in bad loans and possibly a financial crisis. With China now

an engine in the global economy and international investors joining in on the Chinese

investment binge, a hard landing could jolt world markets.

Apart from the risks in the real estate market, economists note surging manufacturing

capacity in already glutted industries.

China's auto industry has enough capacity to make 8 million units a year, far above the

5.7 million in sales in 2005. Supplies of about 70 percent of all consumer goods exceed

demand, according to the Ministry of Commerce-- factors that contributed to a tripling

in China's exports in the past five years.

Exactly where is the good news in this "growth"? Half the GDP is investment

money from abroad or borrowed from shaky central banks, and much or even most of

that vast ocean of money has been mis-allocated into bubble-market luxury real estate

or industries which are already bulging with over-capacity.

Exactly where is the good news in this "growth"? Half the GDP is investment

money from abroad or borrowed from shaky central banks, and much or even most of

that vast ocean of money has been mis-allocated into bubble-market luxury real estate

or industries which are already bulging with over-capacity.

This is a recipe for fiscal disaster, not sustainable growth. The dominoes are

rather obvious: China is massively dependent on trade with the U.S. (for more on this,

see the excerpt below); as this trade shrinks with a U.S. recession, Chinese exports--and

profits, wages, etc.--will be negatively impacted.

China is also dependent on either domestic loans (which have a long

and ruinous history of being allocated for graft or political reasons rather than

financial reasons) or direct foreign investment, which has a hisotry of rapidly drying up

in times of recession or uneasiness.

Some cheerleaders claim China no longer needs exports to grow, that it can prosper

just from the rise of domestic consumers. This excerpt demolishes that absurd hope.

If you want a detailed precis on the complexities of U.S.-China trade, read the entire

two-part story:

PART 2: The US-China trade imbalance

By Henry C K Liu (published in the Asia Times:

These figures show that trade is now a precariously excessive portion of Chinese GDP. And

without a trade surplus with the US, China would face a global trade deficit of about 6.25%

of GDP, more than the United States' 5.7%.

China's addiction to trade:

With any addiction, initial euphoria soon turns to agony. Chinese per capita GDP was $1,231

for 2005, while the country's per capita foreign-trade volume was $1,000. Take away foreign

trade, and Chinese per capita GDP would be $231, or 63 cents a day. And that number is per

capita GDP, not per capita income, which is usually lower.

In 2005, the per capita annual income of Chinese urban residents was 10,493 yuan, or $1,294

at the official exchange rate of 8.11 yuan to a dollar. The per capita annual income of

rural residents was 3,255 yuan, or $401. In fact, in the rural interior, non-trade-related

per capita GDP in 2005 was actually below overall per capita income, meaning that rural

per capita income in region with no export trade had to be subsidized to the tune of $170

per capita, the gap between $401 and $231, or 47 cents a day.

The global poverty line is set at $2 per day, substantially higher than China's

non-trade-related per capita GDP of 63 cents per day. Chinese policy of export-dependent

growth is causing mounting social unrest with serious political implications, which the

government is just beginning to acknowledge.

Obviously, China is much more trade-dependent than the US, and it does not take much

analysis to see that the US commands much more market power in trade negotiation with China.

The fault of GDP as a gauge for growth is plainly displayed in China, where double-digit

GDP growth has given the country a booming economy on paper but one with widening income

disparity that keeps the majority in poverty, irreversible environmental deterioration,

rising moral apathy, systemic official corruption and spreading social unrest. It is hardly

a picture that fits the world's second-largest creditor nation.

The fault of GDP as a gauge for growth is plainly displayed in China, where double-digit

GDP growth has given the country a booming economy on paper but one with widening income

disparity that keeps the majority in poverty, irreversible environmental deterioration,

rising moral apathy, systemic official corruption and spreading social unrest. It is hardly

a picture that fits the world's second-largest creditor nation.

Dollar hegemony has not done better for the US, where the Gini index for 2005 was 0.41.

A Gini index above 0.4 is considered socially destabilizing and economically inefficient.

China's foreign reserves have continued to rise, passing $800 billion by the end of 2005,

and may rise to $900 billion or $1 trillion by the end of 2006. Between 2000 and 2005,

China's foreign reserves increased by more than $600 billion. But this is not surplus

national wealth, but a reflection of deficiency in social-security funding caused by

market reform.

Most US journalists, and almost all politicians, line up with the dollar bears in fixating

on the trade deficit rather than on the capital surplus. And they blame that deficit on

China as the newest scapegoat that carries a great deal of residual hostility from Cold

War days and even from century-old racial prejudice.

According to the China-bashers, the US is a victim of Chinese mercantilism, notwithstanding

that mercantilism involve the quest for gold, not fiat currencies. As they tell it, China

has kept its currency undervalued to promote export-led growth. To back this assertion they

point to China's rapid buildup of foreign-exchange reserves, which are really loans to the

US to balance its trade deficits, notwithstanding the fact that the exchange rate has been

in effect for more than a decade, that China withstood temptation to devalue the yuan after

the 1997 Asian financial crisis, and that fixed exchange rates were a US idea at Bretton

Woods when the United States was a creditor nation.

A wholesale opening of China's financial sector as demanded by the US would require China

to cure the massive non-performing-loan problem in the Chinese banking system as defined

by the Bank of International Settlement (BIS). This is a structural problem that arose from

shifting from a regime of national banking to central banking. This task is ultimately going

to cost upwards of $1 trillion (see China: Banking on bank reform, June 1, 2002). Making

the yuan freely convertible will require upwards of $500 billion to ward off speculation.

Add it all up, and China needs foreign reserves on the scale of $2 trillion to implement

financial liberalization. It is less than halfway there and will not reach the necessary

target if current US policy on China prevails.

A wholesale opening of China's financial sector as demanded by the US would require China

to cure the massive non-performing-loan problem in the Chinese banking system as defined

by the Bank of International Settlement (BIS). This is a structural problem that arose from

shifting from a regime of national banking to central banking. This task is ultimately going

to cost upwards of $1 trillion (see China: Banking on bank reform, June 1, 2002). Making

the yuan freely convertible will require upwards of $500 billion to ward off speculation.

Add it all up, and China needs foreign reserves on the scale of $2 trillion to implement

financial liberalization. It is less than halfway there and will not reach the necessary

target if current US policy on China prevails.

If the Chinese economy hits a stone wall, as it will when the US debt bubble bursts and

Chinese export to the US falls drastically, Chinese sovereign debt will lose credit rating,

causing yuan interest rates to rise, causing more hot money into China, causing the PBoC to

buy more US Treasuries, forcing dollar interest rates to fall and more hot money to rush

into China, turning the process into a financial tornado that will make the 1997 Asian

financial crisis look like a harmless April shower.

This happened to Japan, but with

foreign trade constituting only 18% of GDP in 2003, Japan was able to contain the

deflation domestically. Still, the impact of protracted Japanese deflation on the global

economy was substantial. With China, where foreign trade hovers above 81% of GDP, with

an economy already highly concentrated on the coastal regions and unbalanced with

little breadth and depth, a financial crisis will transmit beyond its borders quickly.

This is the real danger for dollar hegemony.

As a lagniappe, read these, too:

Why the U.S. China Trade Imbalance is Unsustainable.

China Snags (An interesting long view, written by an American who has lived in taiwan

for several years.)

Find Out About Admiral Zheng's Fabulous Fleet!

ads by Groogle

For more on this subject and a wide array of other topics, please visit

my weblog.

copyright © 2006 Charles Hugh Smith. All rights reserved in all media.

I would be honored if you linked this wEssay to your site, or printed a copy for your own use.

|

|

First, let's acknowledge--and dismiss--the main subtexts which play out in any

discussion of U.S.-China trade: Many of the

"China is the inevitable superpower of the 21st Century" crowd are, beneath their

cheerleading, deeply anti-American; they hope China replaces the U.S. as the global

superpower not because they are enamoured of China (though they may be) but because

they loathe the policies and indeed, the power, of the U.S. In this they are akin to the Soviet

sympathizers who romanticized life in the Cold War gulag/USSR because they disapproved of U.S. policy

and power.

First, let's acknowledge--and dismiss--the main subtexts which play out in any

discussion of U.S.-China trade: Many of the

"China is the inevitable superpower of the 21st Century" crowd are, beneath their

cheerleading, deeply anti-American; they hope China replaces the U.S. as the global

superpower not because they are enamoured of China (though they may be) but because

they loathe the policies and indeed, the power, of the U.S. In this they are akin to the Soviet

sympathizers who romanticized life in the Cold War gulag/USSR because they disapproved of U.S. policy

and power.

I do not ascribe to either of these uninformed, ideologically-driven islands of ignorance.

Yes, China was once a great power (circa 1450 and before), and it may yet become a

global power, but it is not yet a global power and it has many challenges to overcome. Like any

other large nation, it will naturally have some areas of disagreement with the U.S. but

it need not be viewed as an either-or alternative to U.S. power. The Pacific, and indeed, the world,

is big enough for Japan, China, and the U.S. to be large economic and military powers. Yes,

Taiwan provides a dangerous point of friction which could lead to open war, but that scenario

is by no means inevitable.

I do not ascribe to either of these uninformed, ideologically-driven islands of ignorance.

Yes, China was once a great power (circa 1450 and before), and it may yet become a

global power, but it is not yet a global power and it has many challenges to overcome. Like any

other large nation, it will naturally have some areas of disagreement with the U.S. but

it need not be viewed as an either-or alternative to U.S. power. The Pacific, and indeed, the world,

is big enough for Japan, China, and the U.S. to be large economic and military powers. Yes,

Taiwan provides a dangerous point of friction which could lead to open war, but that scenario

is by no means inevitable.

Sounds great, doesn't it? But if we look beneath the surface statistics, there are some

very troubling imbalances. Let's turn to Elaine Kurtenbach's (of the Associated Press) piece

China struggles to tame economy. The presence of a real estate bubble is now

undeniable, as is the astonishing dependence of China on investment for its growth:

Sounds great, doesn't it? But if we look beneath the surface statistics, there are some

very troubling imbalances. Let's turn to Elaine Kurtenbach's (of the Associated Press) piece

China struggles to tame economy. The presence of a real estate bubble is now

undeniable, as is the astonishing dependence of China on investment for its growth:

Exactly where is the good news in this "growth"? Half the GDP is investment

money from abroad or borrowed from shaky central banks, and much or even most of

that vast ocean of money has been mis-allocated into bubble-market luxury real estate

or industries which are already bulging with over-capacity.

Exactly where is the good news in this "growth"? Half the GDP is investment

money from abroad or borrowed from shaky central banks, and much or even most of

that vast ocean of money has been mis-allocated into bubble-market luxury real estate

or industries which are already bulging with over-capacity.