|

| weblog/wEssays | home | |

|

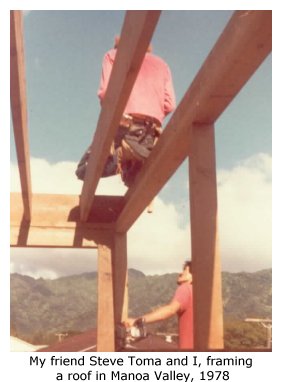

A Degree of Success (June 2005) "De-industrialization" has an ugly sound to it, and for the millions of workers who've lost manufacturing "blue collar" jobs in the U.S. over the past two decades, it's had an ugly consequence: gone are high wages and benefits and more or less permanent employment. Even worse, jobs for those without college degrees have lost the mobility which once allowed an ambitious worker to rise to higher skill and pay levels. The Wall Street Journal has been publishing a series describing this reduced mobility in the U.S. economy for less educated workers; the latest is As Economy Shifts, a New Generation Fights to Keep Up. The evidence is straightforward: the odds of a person getting a college degree are linked to whether their parents earned a degree or not; "An American has a 62% chance of getting a bachelor's degree if either parent did, but only a 19% chance if neither parent did, according to Bruce Sacerdote, a Dartmouth College economist." As we all know, a college degree is now requisite for a good livelihood. Or is it that simple? The San Francisco Chronicle just ran a story bemoaning the shortage of young workers willing to learn the "blue collar" trades the local refineries need to continue operations: Who Will Fill Baby Boomers' Big Work Boots? One of the reasons, it seems, is that high school graduates have been drilled that college is the only pathway to a decent career. Meanwhile, high-paying jobs are going begging, and the refineries are increasing their training programs to ensure they will still have welders and machinists in ten years. What has happened in the U.S.--the loss of low-skilled manufacturing jobs to places with lower costs-- has been going on for centuries. As historian Fernand Braudel has shown, capital and manufacturing have shifted from region to region and industry to industry for hundreds of years. Lyon, France was once a great silk-weaving center, for instance; it lost that industry long ago. But there is a difference between a line assembly job which can be taught in five minutes and an actual skilled trade. Some 16% of the U.S. economy is still manufacturing related, but the jobs require higher and higher skills. There are also millions of jobs in the building trades, auto maintenance, etc. which are well-paid and do not require a college degree--though they do require knowledge, training and expertise.  I wonder if this dichotomy doesn't reflect a generational gap in values. We of the Countercultural Era (hippies,

activists, etc.) valued self-sufficiency; we changed the oil in our own car, tended gardens, baked bread, learned

to sew, built our own houses, and started our own businesses not because it was a career path per se but because

we valued authenticity (real food, real skills, etc.) over convenience or consumerism. We rebelled at the thought

of living out our productive lives in some sterile, stratified cubicle and corporate structure of bosses and

bosses' bosses. As a result, many of us

became mechanics or carpenters--even with our college degrees.

I wonder if this dichotomy doesn't reflect a generational gap in values. We of the Countercultural Era (hippies,

activists, etc.) valued self-sufficiency; we changed the oil in our own car, tended gardens, baked bread, learned

to sew, built our own houses, and started our own businesses not because it was a career path per se but because

we valued authenticity (real food, real skills, etc.) over convenience or consumerism. We rebelled at the thought

of living out our productive lives in some sterile, stratified cubicle and corporate structure of bosses and

bosses' bosses. As a result, many of us

became mechanics or carpenters--even with our college degrees.

Many skilled jobs remain localized; you can't ship your car to China for a tuneup, for instance, or outsource the maintenance of a refinery to India (unless you ship the entire refinery to India first). Many are undoubtedly entrepreneural in nature, meaning that you don't "get a job," you "make a job." I wonder if young people now--who famously do not know how to cook--want to actually learn how to do things, or if they just want a "good paying job" in a clean little cubicle somewhere. There are those service jobs, of course, millions of them; but they may not be all they're cracked up to be, and the mobility within those corporations may not be as wonderful as the "standard model" suggests. * * * copyright © 2005 Charles Hugh Smith. All rights reserved in all media. I would be honored if you linked this wEssay to your site, or printed a copy for your own use. * * * |

||

| weblog/wEssays | home |