|

| weblog/wEssays | home | |

|

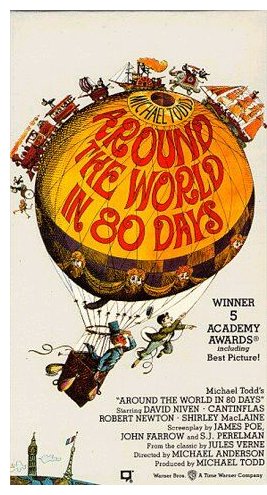

When Empire Was Easy: Around the World in 80 Days (September 27, 2005) The Jule Vernes story Around the World in 80 Days

Phileas Fogg, the emotionless, neurotic epitome of an upper-crust Englishman (David Niven) does basically nothing, while his "gentleman's gentleman" valet, Passepartout, (Cantiflas) performs all the heroics. Niven spends most of the film checking his watch and regally enjoying his tea, rain or shine, while Cantiflas braves the rigors of the bull-fighting ring, clambers atop a speeding train beset by attacking Sioux (sadly lacking the firearms they most certainly possessed by the 1870s), and rescues a Princess in India from a blood-thirsty horde while the upper-class Englishmen watch from a safe distance--hmmm. The one moment of physical courage Fogg endures is a foolish, prideful duel with a cantankerous cliche of a Southern gentleman, a duel which is interrupted by a propitious attack on the train by "Red Indians." I haven't read the book since childhood, but I wonder if this isn't an American subtext of sorts--we did, after all, throw off the weight of the Empire at the cost of a seven-year war which was both a world war (recall that we won thanks to the French fleet blockading Cornwallis' army from re-supply or evacuation) and a civil war in which at least 40% of the populace either actively or passively considered themselves loyal British subjects. With our own "Empire" (not of territories so much as influence and alliances) girdling the globe as a result of being "last man standing" at the end of World War Two, this film reflects the American ambivalence to Empire. The British overlords are portrayed as supercilious, petty buffoons, confident in their right to rule but doing nothing for themselves, quite content to order their servants around. Yet the structure which enabled the Empire to work gets a favorable treatment; Fogg cannot be arrested in Cairo by the incompetent British detective tailing him because the warrant has not yet arrived from London, and the Imperial ships and trains all leave on schedule. The film offers a model of global reach which was admirable in its orderliness, functionality and rule of law. Of course the moral righteousness of the Empire is made clear: heathen "natives" are either burning the poor Princess (played by very pale Shirley McClaine) on a funeral pyre or trying to torch poor Cantiflas at the stake (during the hopelessly campy "Cowboys and Indians" sequence). The viewer cannot help but be struck by the leisurely pace of the film. Segments which would be cut to a few manic seconds in a modern version are allowed to unfold in real time: a Spanish dance, Cantiflas' fledging efforts as a bull fighter, scenes of the Indian countryside from the train window, etc. It's hard not to conclude that modern audiences suffer from attention-deficit syndrome and cannot bear to watch any scene in real time except intricately plotted "action" sequences. There are exceptions, of course, and these are often the better films of our era. I recommend the film not just for its cast and dialogue or as a snapshot of a bygone era in film-making, but for its fascinating array of subtexts. * * * copyright © 2005 Charles Hugh Smith. All rights reserved in all media. I would be honored if you linked this wEssay to your site, or printed a copy for your own use. * * * |

||

| weblog/wEssays | home |