|

| weblog articles | fobidden stories I-State Lines resources my hidden history reviews | home | |

Asia's Unfolding Crises CHINA Resources: Websites China.org.cn "Energy and Power in China" The Foreign Policy Centre Beijing Review The China Business Review Resources for the Future Elite Chinese Politics and Political Economy China Daily BizAsia.com "Witness to a Crisis" (Far Eastern Economic Review) Journal of Asian Law (Columbia University) "China as a Great Power" Prof. Samuel S Kim, in Current History) International Monentary Fund Congressional Budget Office Cato Institute Economic Policy Institute Books The River Runs Black: The Environmental Challenge To China's Future by Elizabeth C. Economy The Future of Life by E. O. Wilson Mao's War against Nature : Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China by Judith Shapiro China's New Rulers: The Secret Files by Andrew J. Nathan and Bruce Gilley China Wakes : The Struggle for the Soul of a Rising Power by Nicolas D. Kristof River Town: Two Years on the Yangtze by Peter Hessler The River at the Center of the World : A Journey Up the Yangtze, and Back in Chinese Time by Simon Winchester The Good Women of China : Hidden Voices by Xinren Xue Wild Swans : Three Daughters of China by Jung Chang Hungry Ghosts : Mao's Secret Famine by Jasper Becker BIG DRAGON : The Future of China: WHAT IT MEANS FOR BUSINESS, THE ECONOMY, AND THE GLOBAL ORDER by Daniel Burstein Mao : The Unknown Story The Private Life of Chairman Mao by Li Zhi-Sui The Great Wall and the Empty Fortress: China's Search for Security by Andrew J. Nathan China Dawn: The Story of a Technology and Business Revolution by David Scheff Streetlife China by Michael Dutton China's New Order : Society, Politics, and Economy in Transition by Hui Wang Red Sorrow: A Memoir by Nanchu |

China: An Interim Report: Its Economy, Ecology and Future (first published June 20, 2005; Updated: April 9, 2006) The hard-working Chinese people deserve prosperity, stability and health, but the long-term prospects for all 1.2 billion citizens of the People's Republic remain an open question. I am no more than an interested student of the country and culture, but I do have two resources: numerous Chinese friends, and a perspective gained from 30 years of reading augmented by two somewhat unique visits. My goal is not to list the various obstacles in China's path (although that is a necessary first step), but to describe the structural impediments to its continuing success--and how they could be overcome. Although these are well-known and well-documented, I haven't found a comprehensive overview of all the primary issues; this is an attempt at such a summary. That the Chinese people possess all the traits needed for great success is self-evident. The question is whether their leadership and the structure of their current society possess the traits needed to solve the enormous environmental, financial and social problems facing the nation. The Impediments to a Realistic Appraisal The concepts of 'Face' and national pride make most Asians extremely reluctant to criticize their own nation. This is certainly true in China. The usual pattern I encountered was as follows: problems facing China are quickly acknowledged, then lip service is paid to "learning from America" or the West, implying the solutions are already being implemented, and then the conversation moves quickly to America's problems or weakening position in the world.  In other words, the acknowledgement shows the willingness to criticize, which is a sign of strength, but

the follow-up discussion of solutions boils down to "saving face."

Thus I have been assured that political freedoms

in China are equal to those in the U.S. because the speaker was a member of a political party other than the

Communist Party. While technically speaking, this was accurate--there are four officially

sanctioned alternative parties, represented by the smaller stars on the PRC flag--the substance of his assertion was

absurd.

In other words, the acknowledgement shows the willingness to criticize, which is a sign of strength, but

the follow-up discussion of solutions boils down to "saving face."

Thus I have been assured that political freedoms

in China are equal to those in the U.S. because the speaker was a member of a political party other than the

Communist Party. While technically speaking, this was accurate--there are four officially

sanctioned alternative parties, represented by the smaller stars on the PRC flag--the substance of his assertion was

absurd.

In similar fashion, I have been assured by a young man (all conversations were in English, as I don't speak Mandarin) that his father was drawing a comfortable pension, along with the majority of other old people in China. The elderly beggars clustering around me at every train or bus station certainly suggest that isn't quite accurate; as for the Chinese themselves, when an elderly female supplicant makes her way down the subway car in Shanghai, palms outsretched in the universal sign of begging, virtually every young Chinese person averts their gaze or continues their cellphone conversation as if the woman doesn't exist. I witnessed only one young woman open her purse to give a frail grandmotherly beggar a few coins. Is this any different than in the U.S.? Of course not; there are ragged, obviously disturbed men and women huddled on the streets of every American metropolis. The difference is that few Americans would baldly assert an obvious non-truth, i.e. that homelessness is not a problem in America. They might rant about their preferred solution, but they would be unlikely to deny the problem exists. The concept of "face' is certainly pan-Asian, and it can best be described to Westerners not familiar with its power as the cultural necessity of presenting a positive facade to the world, even if truth and accuracy must be sacrificed as a result. National pride and face are intertwined in Asia, adding another impediment to realistic appraisals. There is no shortage of national pride in America, France, or indeed any other nation, but in Asia the natural pride in one's heritage is entangled with the cultural imperative of "saving face" and a strong desire to right (or obscure) the injustices of the past century.  In China, this manifests itself in the pride experienced in reclaiming Hong Kong, and the near-universal

desire to reclaim Taiwan as the "lost province" unjustly taken from China by imperialistic foreigners.

In China, this manifests itself in the pride experienced in reclaiming Hong Kong, and the near-universal

desire to reclaim Taiwan as the "lost province" unjustly taken from China by imperialistic foreigners.

It is difficult, I think, for Americans to fully grasp the damage done to Chinese pride when the Western powers occupied parts of mainland China. An analogy might be to imagine China occupying Los Angeles in 1901, and then setting aside much of San Francisco for a "Chinese-only" concession. That such land-grabs would stick in the craw of the occupied nation is entirely understandable--especially if that nation believes its natural role, indeed its only possible role, is to be a great world power. China's people hold a strong sense of China's grand, even unequaled history as the center of the civilized world (hence the term still used today to denote Caucasians, "Foreign devils"), and a belief in the historical imperative thus bequeathed to the nation. A comparison to the American concept of "Manifest Destiny" is imperfect but instructional, I think, in communicating the Chinese desire to reclaim the greatness that was once theirs alone. This concept provides a bridge of understanding to the Chinese sense of being put upon or restrained by the West, and America in particular, even when it is obvious that America is simply acting like any other nation, i.e. in its own self-interest. But an understanding that America is not "out to limit China" but is simply pursuing the best interests of itself and its allies is rare in China; U.S. actions in the Pacific are seen to revolve around China rather then the needs of U.S. constituencies or a complex U.S. foreign policy. Since China's political structure currently precludes a freely distributed, independent media, there is no counterbalance to the official desire to manipulate public opinion and obscure corruption. Skepticism of the official party line is the fundamental stance of Western media; as a free-lancer in the media, I can assure you that any story which is too "happy-happy" or insufficiently skeptical of received truths will be sent back for further research and revision.

While there are many in the U.S. with the same naive, parochial blinders--that is, seeing all Chinese policies as reactions to U.S. initiatives--the U.S. media is not in lockstep with this view. But the media in China is tightly controlled, and so skepticism of the official worldview is not permitted. By way of example, imagine a Chinese equivalent of the May 9th issue of Newsweek which glorifies "China's Century" on the cover. While you'd find Chinese agreeing most whole-heartedly with Newsweek's thesis, you would never find a national magazine in China trumpeting the prospects of "The American Century" extending through the 21st century--that is, glorifying America's prospects for continued global dominance. The cultural imperative to present a positive front inhibits the collection and distribution of accurate data on the nature and scope of China's problems. Without accurate and unflinching data, problems cannot be assessed or solved. In the bad old days of the cult of personality, the fields of rice along certain roadways were famously overseeded to give the passing Chairman Mao the impression that the current crop of rice was stupendously abundant. In reality, the crop was a disaster and millions died of famine--a disaster hidden from the Chairman for reasons of face and political jockeying. It would be rash, I think, given the questionable reliability of statistics in China, to claim that such "doctoring" or manipulation of evidence and data is a thing of the past. Indeed, many carefully anonymous reports suggest that such misrepresentation to give the appearance of progress is structurally endemic. This is a troubling prospect, for without accurate data, long-term solutions (and the feedback necessary to improve those solutions) are effectively thwarted. Consider a recent survey of 3,000 Chinese bankers and brokers posted by Victor Shih, assistant professor of political science at Northwestern University. According to this survey, 82% of respondents reported that corruption in China's financial sector is either "very common" or "fairly common." These insiders also report that when a company or individual defaults on a loan, they are pursued for payment only 13.7% of the time; in 46% of the cases, defaulters aren't even identified, much less pursued; in the remaiing 40%, the defaulters are known but not pursued, or pursued half-heartedly.

The survey was broad enough that it cannot be dismissed as a poor sampling. It clearly suggests that the efforts being made by the central government to "clean up" the Chinese banking sector have been largely ineffective. The question is: does the central government have the tools to permanently re-work the sector's culture of laxness and corruption? If it does, then why has the clean-up been so ineffectual? For further evidence, consider this quote from Professor Shih's website: Last year, the China Banking Regulatory Commission despatched 16,700 teams to investigate just how much the situation had really deteriorated from 2003. Shockingly, they uncovered 584 billion yuan in illegal funding by banks and financial institutions, compared to the 407.2 billion discovered the previous year. Altogether, 2,202 financial institutions were implicated in the commission's investigations, involving 4,294 officials and staff. Yet only two banks with foreign investment were found to have problems.This suggests not a system being reformed but a system which is simply perfecting ways to evade whatever weak regulations and oversights are put in place by the central government. The Systemic Nature of Corruption The problem isn't just the vast scope of corruption and denial revealed in this survey; it's that the incentives in the system reward corruption and punish both honesty and the collection of rigorous data. Human being are very predictable in one regard; like all organisms, they will respond to rewards and punishments. If you "play the game" of accepting bribes or other forms of compensation for making loans, everyone up the chain from you (i.e. your boss and his boss, the local party boss, and so on) is happy, because they will continue to get their cut of the action. Playing straight would disrupt the entire system, and degrade or eliminate the perks enjoyed by everyone with a position in the current system.

In a similar fashion, actually pursuing defaulters would quickly ensnare those in the same circle of power who authorized the loans in the first place, for the granting of loans is all too often part of the unvirtuous cycle of corruption: I'll arrange for you to receive this huge loan, and you will respond in kind (a generous bribe, a cut of the deal, or some other compensation) which I then distribute to cronies and my bosses to enhance or sustain my own position in the system. You are free to use the money for whatever you want--very likely a poor business prospect or some sort of speculation--and when the deal goes sour then you don't even have to pay the money back. There are no incentives to either mid-rank employees or top management to actually reform this system, and no punishment for those who propagate it. True, when a corruption case is so egregious that it angers the populace, then the Party requires a few managers or officials to fall on their swords; but this "punishment by example" is not systemic or rigorous; everyone knows it's window-drssing to save face, and to convince (or attempt to convince) the general populace that the Party is serious about its perpetual "anti-corruption" campaigns. Few in China believe such campaigns are consistent or rigorous, or even that they're intended to be effective; but since such blatant and systemic corruption makes China look bad, everyone plays along with the notion that the central government is "really doing something" about corruption.  Without an independent judiciary (empty claims to the contrary notwithstanding), China lacks a mechanism

to stem such systemic corruption. Countries with low corruption

(as per a survey of 102 countries compiled by the anti-corruption organization transparency.org)

are generally small nations with long histories and strong cultural support for independent judiciaries

and honest/transparent governance--Finland, Denmark and New Zealand top the list.

Without an independent judiciary (empty claims to the contrary notwithstanding), China lacks a mechanism

to stem such systemic corruption. Countries with low corruption

(as per a survey of 102 countries compiled by the anti-corruption organization transparency.org)

are generally small nations with long histories and strong cultural support for independent judiciaries

and honest/transparent governance--Finland, Denmark and New Zealand top the list.

Interestingly, Asian countries with a recent (and relatively short) history of independent judiciaries--Singapore and Hong Kong--score as high or higher than very-low-corruption nations such as Sweden and Canada. It is with some small irony that we note that the top-ranked large country (i.e. those with 50 million or more citizens) is Great Britain with a ranking of 8.7 (#10 in the list of 102). Hong Kong earned a ranking of 8.2 (14th), while the U.S. (16th) came in at 7.7 (roughly in line with Austria, Chile and Germany), while China (59th) has a ranking of 3.5, in line with Mexico, Egypt and Ethiopia. Bangladesh (102nd) came in last with a ranking of 1.2, just below nations like Nigeria, Madagasgar, Indonesia, Azerbaijan, Paraguay and Uganda. For comparison's sake, China's great-power neighbors, Russia and India, both received a ranking of 2.7, (71st), Systemic corruption cripples a nation in three key ways: it undermines meritocracy; it misallocates capital, and its root injustice breeds resentment and distrust of institutions. It is generally accepted that the citizenry of the U.S. tolerates an enormously imbalanced concentration of wealth--5% of the population owns 59% of all the nation's assets-- because they believe that "getting ahead" is based not just on family wealth but also on merit and virtuous habits (working hard and saving/investing). Though the U.S. has the highest such concentration of personal wealth in the world, I think it is self-evident that virtually every other prosperous nation on the planet has a similar pyramid of wealth, and a similar faith in individuals' potential to improve their position through merit and virtuous habits.  On the other hand, societies in which position, wealth and prestige are largely assigned through

bribery, party status, caste, ethnicity, religion, etc., are inherently unstable and unprosperous. This is so

self-evident that it cannot be plausibly contested.

On the other hand, societies in which position, wealth and prestige are largely assigned through

bribery, party status, caste, ethnicity, religion, etc., are inherently unstable and unprosperous. This is so

self-evident that it cannot be plausibly contested.

While meritocracy is certainly present in China--witness the story of Weijian Shan as reported in The Economist--so is favoritism and decisionmaking based on relationships rather than merit (i.e., on the merits of a person's "guanxi"). According to a confidential study in China, only 5% of the richest 20,000 people in China made it on merit. Clearly, meritocracy plays a severely limited role in the distribution of the nation's new-found wealth. Guanxi is not easily translated into English; it is not a synonym for corrupting relationships but for a broad range of relationships of varying strength and obligation. In a nutshell, Guanxi may fall into to one of these three categories: 1) a relationship between people who share a group status or are related, e.g. family or co-workers 2) connections between people who have frequent contact, such as business associates and 3) contacts between people who have little direct interaction, e.g. business conducted with overseas connections, etc. Guanxi can simply mean a diplomatic exchange of gifts as a sign of respect, or it can provide a mechanism for dispute resolution, establishing a new relationship or even collective decision-making. It is best understood, I think, as an essential cultural component of Chinese society. It should be viewed not as an impediment to meritocracy but as a condition which, if unchecked by policies backed up by the rule of law, can undermine meritocracy and individuals' sense that they have a chance to better themselves by abiding by the rules. This undermining of people's faith in meritocracy has two devastating consequences: 1) better-qualified people are passed over, relegating the nation's talent to lesser positions while rewarding incompetence, and 2) the unfairness fuels resentment in those with insufficient guanxi to level the playing field. In China this constitutes the majority of citizens. And who can blame them for feeling left out of the virtuous circle through not fault of their own? Misallocation of capital dooms a nation to stagnation. Misallocation of capital is simply a way of saying that money is poorly invested when the decisions to loan or invest are made not on sound business grounds-- i.e., earning a return for investors--but on relationships (e.g. "guanxi"). In a market economy, once production reaches a balance with demand, then money should stop flowing into building new manufacturing plants, as increasing supply will only suppress the price of the goods. A rising oversupply inevitably leads to a collapse in profits and a subsequent rise in bankruptcies and loan defaults.  Thus, misallocated capital sinks some industries into unprofitablity, while depriving more

productive industries of much-needed capital. (For an example of this in

action, consider the

television manufacturing industry in China--as reported on china.org.cn.)

The

potential for overinvestment in steel and a subsequent collapse of profitability has been covered by the

Wall Street Journal.

Thus, misallocated capital sinks some industries into unprofitablity, while depriving more

productive industries of much-needed capital. (For an example of this in

action, consider the

television manufacturing industry in China--as reported on china.org.cn.)

The

potential for overinvestment in steel and a subsequent collapse of profitability has been covered by the

Wall Street Journal.

China has two well-documented mechanisms which systemically misallocate capital: corruption and the need to prop up state-owned businesses with bank loans. While a "clean-up" of bad loans in the big four state-owned banks is being heralded as a "solution" (bad debt is now officially only $230 billion), evidence suggests that bad loans are being made as fast as the old mountain of bad debt is liquidated (sold off at pennies to the dollar to Western banks). As a result, the billions in new capital the state has been putting into the banks is being squandered. In other words, if the system for granting, tracking and collecting loans hasn't been completely transformed, then the central government's efforts to dispose of old bad debt from bankrupt state-run businesses is simply clearing the decks for a new round of bad loans. The billions of new capital the government is pumping into the state banks will inevitably be misallocated, as the underlying culture hasn't been changed. A remodeled facade has been erected, but that is not the same as rebuilding the structure from the ground up. The suspicion in some circles is that the government is simply window-dressing a bankrupt banking system in order to attract new capital from the West and from the overseas Chinese community. The new capital wouldn't change anything fundamentally, but it would prop up the system for a few more years--time in which the government hopes to transform a systemically corrupt culture and industry into a functioning equivalent of Western financial institutions. But given the systemic nature of corruption, the huge incentives to its continuation, the disincentives to changing it from within, the lack of an independent force strong enough to overcome the purposefully obscure manner in which local party officials, bank officials and other power players influence loans, this hope seems just that--a hope ungrounded in the actual structure and mechanisms of the banking sector, economy and government. Local officials seek new factories--and the loans to build them--to create new jobs and increase prestige. Why should they sacrifice growth in their district just to meet some Beijing goal to limit new loans? The misallocation of today's huge influx of capital may be a mistake of historic proportions. While popular belief in the permanence of China's investment boom is high, history suggests the opposite possibility: that the current massive flow of investment into China is a one-time event. If true, then the squandering of these hundreds of billions on projects of dubious worth will be seen in the future as a waste of capital on par with the Cultural Revolution.  Since data cannot be trusted, who would trust assurances that the banking industry is now "transparent"?

Given the intractable nature of corruption and its reach into every nook and cranny of the Party and the banking system,

the more accurate assessment might be that a facade of transparency is being erected to further hide the actual workings of the system.

Since data cannot be trusted, who would trust assurances that the banking industry is now "transparent"?

Given the intractable nature of corruption and its reach into every nook and cranny of the Party and the banking system,

the more accurate assessment might be that a facade of transparency is being erected to further hide the actual workings of the system.

Human nature (and history) suggest that people in positions of power are willing to cut the benefits of corruption flowing to someone else, but they will fight to the bitter end to retain their own perquisites. Unfortunately, there is no discernable separation between corruption in the banking sector and corruption in the Party, and as a result all efforts to "reform" one sector or level of the society are a priori doomed to fail. Once a powerful person's toes get stepped on, the "reform" quickly dissipates into mere lip service, a club which is only hauled out of the closet to beat a lower official who had the misfortune of getting caught when public pique was high. Widespread civilian discontent--expressed in both spontaneous and planned demonstrations--is evidence that frustrations stemming from the injustices of corruption and favoritism are increasingly eroding confidence in the central and local government. Even though news of many spontaneous protests is suppressed or not reported in the officially sanctioned press, that such outbursts are on the rise is not in doubt. The corruption of the material world--pirating products and watering down quality for private gain--is endemic, and has serious consequences both within China and in its trade with other nations. Although the headlines tend to focus on pirated software or luxury goods and the prevailing Chinese attitude that the theft or duplication of someone else's design doesn't actually constitute theft, there are very real and very negative consequences to such widespread pirating for the Chinese people. In terms of health, consider that a significant percentage of "official" pharmaceuticals on the shelves in China (about 40% by some reckoning) are worthless sugar pills packaged to look like the real medications. The cost to the Chinese people of such piracy is not just money wasted on worthless knock-offs but in health compromised or lost. Life safety is also an issue in the corruption of construction materials and practises. Stories abound in which contractors substituted inferior materials or installed less steel or concrete than specified in order to pocket the difference in costs. According to published accounts (Judith Shapiro, Mao's War Against Nature--linked in the "resources" column to your left), 2,976 dams had collapsed by 1980; others report that a number of bridges have failed or been declared unsafe as a result of this type of corruption. Again, the counterweights to such exploitation--a free and skeptical press, and an independent judiciary empowered to imprison wrong-doers, no matter what their position or status--are missing, and so this disgraceful corruption of public works continues unabated.  Piracy has a steep economic cost as well. While traveling in China's industrial heartland, a large,

shuttered facility bearing the name of a global pharmaceutical corporation was pointed out to me by an expatriate

resident. It was built with great promise to manufacture modern medicines for the Chinese market, but the

immediate piracy of its products had forced it closure. Chinese customers complained the medicine didn't work--

and of course the sugar pills being distributed in lieu of the authentic drug did not work. So the market

for the company's products dried up, along with any future investment or jobs.

Piracy has a steep economic cost as well. While traveling in China's industrial heartland, a large,

shuttered facility bearing the name of a global pharmaceutical corporation was pointed out to me by an expatriate

resident. It was built with great promise to manufacture modern medicines for the Chinese market, but the

immediate piracy of its products had forced it closure. Chinese customers complained the medicine didn't work--

and of course the sugar pills being distributed in lieu of the authentic drug did not work. So the market

for the company's products dried up, along with any future investment or jobs.

Similar tales are heard in every industry, at every level and every geographic area. The travails of the Japanese motorbike manufacturers are well-known; knock-offs of their bikes are nearly perfect replicas, except for the price of course, which is considerably less than that of a motorcycle built in the Japanese-owned factories. I sat next to an I.T. representative on a flight to Shanghai a few years ago, who explained that their product's software had been copied by a new Chinese competitor. Years of legal action and political pressure had squeezed the competitor into an agreement to work with the legitimate creator of the software. But in the ensuing period, the U.S. firm had lost sales to the "competitor" whose only product was a stolen copy of the U.S. firm's software code and design. I have first-hand knowledge of other smaller manufacturing businesses moving their entire operations in China to either Vietnam (with a low 2.4 rating) or Thailand (rated a 3.2). Though corruption is equally endemic in those nations, it was less destructive to their quality, reputation and market than the travails they'd suffered in China. There are even deeper costs to the ubiquity of pirating and debasement of quality. What Chinese business will risk millions on developing world-class software when no one will pay for it? Why invest in research and development when your product will be quickly copied and marketed for a fraction of your development cost? Will Chinese consumers pay more for the "genuine article" if it's Chinese-designed? It doesn't seem like a good bet. The government may well be funding plenty of R&D, but with rampant pirating accepted as the norm, the question remains: what high-margin, high development-cost products developed in China will find a home market rich enough to reward the initial investment? If entrepreneurs with a long-term view and a desire to innovate lose out to thieves and pirates--often semi-officially sanctioned, it should be noted--then why will they stay in China? "Corrupt political elites in the developing world, working hand-in-hand with greedy business people and unscrupulous investors, are putting private gain before the welfare of citizens and the economic development of their countries," said Peter Eigen, Chairman of Transparency International.Given the untrustworthy statistics and the well-concealed intricacies of dealmaking and piracy, it's difficult to precisely state the true extent of corruption in China; but all available evidence suggests the nation is in the grips of a corruption so deep and pervasive that it could hobble all the great efforts being made to move toward a healthier, more prosperous future. Generational Deadline: Environment, Demographics, Finance China's Environmental Challenges The severity of China's environmental problems is well-documented; an Internet search for "environmental problems" + "China" produces nearly 300,000 references. Less well-examined are the cultural and political underpinnings of the crisis. By and large, China has followed the traditional industrial development model of "massive production, massive consumption and massive discharge." The size of the population and country guarantee that the scale of each issue is staggering:

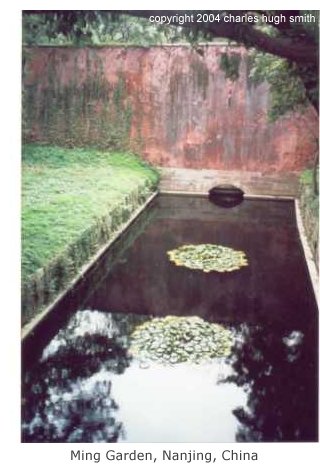

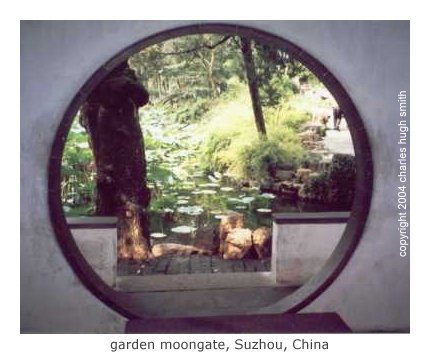

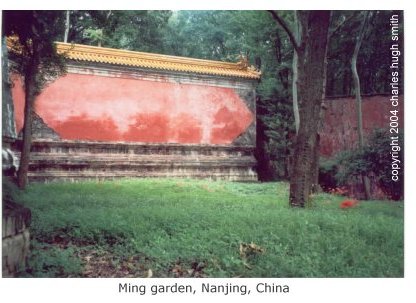

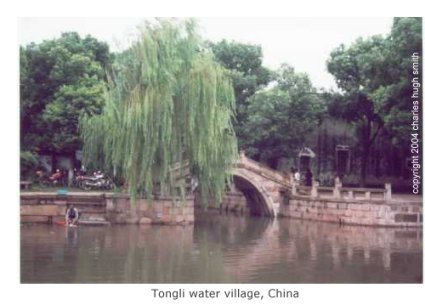

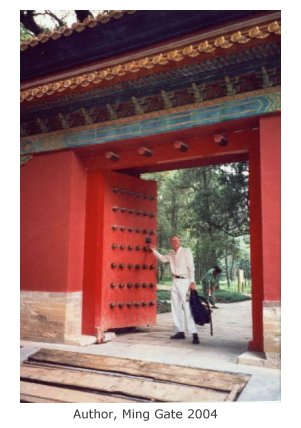

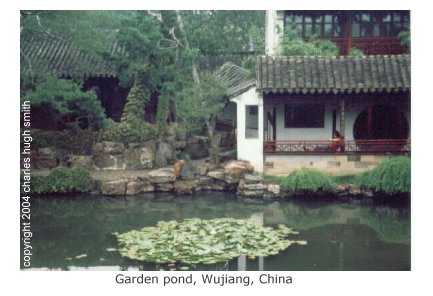

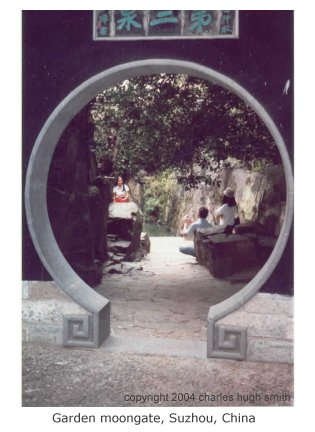

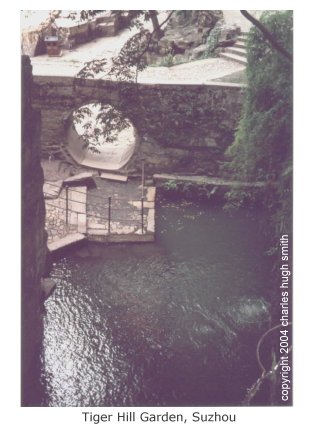

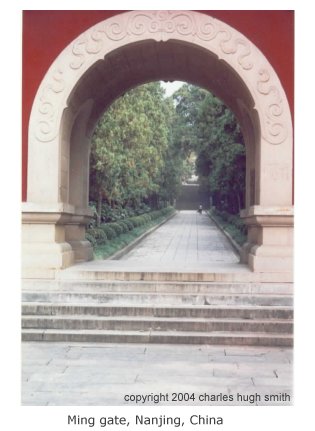

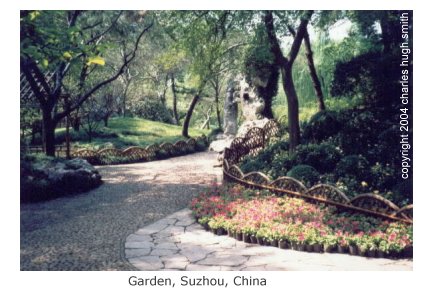

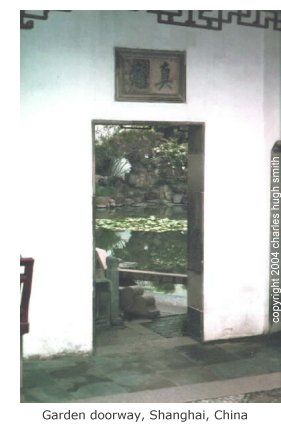

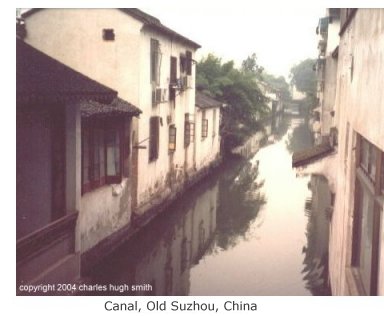

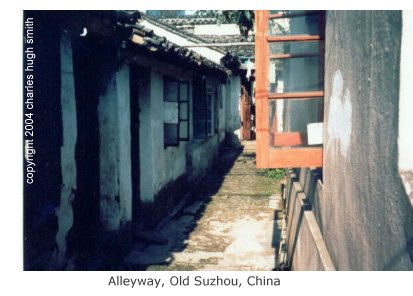

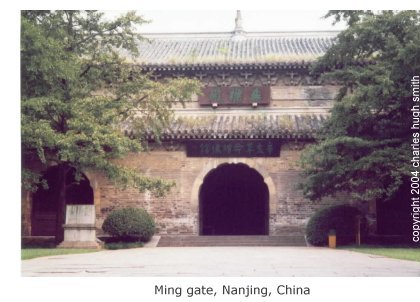

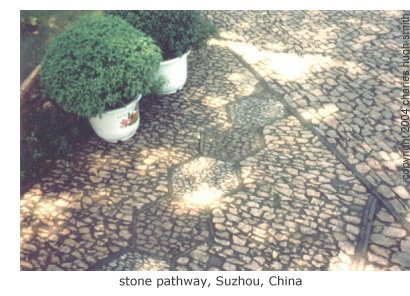

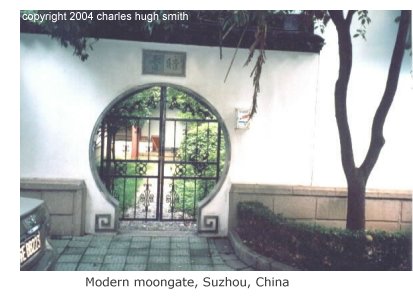

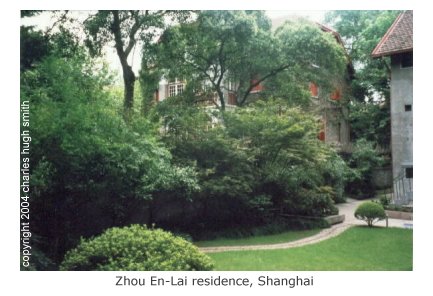

All this data supports E.O. Wilson's view that China is heading toward an ecological bottleneck. How much passes through that bottleneck is the open question. If you read nothing else on China's ecological crises other than this essay, read this excerpt from his book The Future of Life (in the resources column on the left). China's present path is clearly unsustainable, and the future is clouded by the same structural flaws outlined in the previous sections.  You may have noticed that I have illustrated all this bad news with beautiful scenes from some of the gardens

and villages I've visited in China. There is a subtext to this, of course; I wanted to express that China is

far from a wasteland, and that its people have a long history of cherishing Nature and natural beauty.

But an understanding that Nature has limits is not the same as appreciating its beauty.

You may have noticed that I have illustrated all this bad news with beautiful scenes from some of the gardens

and villages I've visited in China. There is a subtext to this, of course; I wanted to express that China is

far from a wasteland, and that its people have a long history of cherishing Nature and natural beauty.

But an understanding that Nature has limits is not the same as appreciating its beauty.

The idea that there is value in Nature being left wild is not a natural one in most human cultures, and China (along with the rest of Asia) is no exception. There are historical precedents in Chinese culture for such an understanding, such as the Taoist and Chan Buddhist poets and writers. But the influence of Mao's "War on nature" (see the book by that title in the resources sidebar) is more recent and more pernicious. Mao's "Great Leap Forward" (and the subsequent famine), suppression of intellectual skepticism/dissent, encouragement of large families, and vast relocations of industry and populations to environmentally fragile landscapes created a legacy of ecological damage which weighs heavily on today's China. There is another subtext to the photos: China's wonderful gardens are intended to feel natural, but they are not natural; they are artful syntheses of human constructs and natural patterns. This ideal, I think, underpins all Asian cultures' deep-seated views of Nature, and informs to some degree the government's responses to environmental issues: people come first, Nature second--until Nature can no longer sustain the people. Then, of course, it's too late. China's explosive development could be summarized thusly: personal gain trumps the shared environment every time. This is the kernel of human behavior at the heart of Garrett Hardin's classic 1968 article Tragedy of the Commons. (Science has posted the original article and additional commentaries.)

The essence of the article is this: the benefits of exploiting whatever resources are freely available to the entire community (air, water, grazing land, etc.) are outsized to the individual, but ultimately catastrophic to all when the common resources are depleted or destroyed by overuse. The situation in China is roughly analogous, with this proviso: the public is excluded from the commons, but Party officials and bigshots are free to exploit whatever shared resources they can control. Sadly, there are few limits on local Party bosses' powers; although the central government appears to hold the reins of power, the chain of command is actually rather weak. Thus you often hear tales in which common folk (generally those in fast-growing urban zones) have been evicted to make way for a shiny new development funded and built by a consortium of local party officials and big-money types (often overseas Chinese from Hong Kong, Taiwan, or elsewhere). The same four structural flaws outlined above haunt the country's efforts to save the country from environmental catastrophe: China's industrial development poses one last great question: are there enough resources left on this planet to feed, cloth, house, transport and entertain another billion voracious consumers? If you include India as a rapidly developing great power, then the number increases to 2 billion--roughly twice the populations of Western Europe, North America and Japan combined.

(graph from the World Wildlife Fund's Living Planet Report) The above graph suggests not. In other words, China's development is straining the limits not just of its own territory and resources, but of the entire planet. In street parlance, it appears the leadership of both China and India blew it by pursuing a centralized, Socialist template of development and (until relatively recently), unconstrained population growth. Having squandered the critical forty years (roughly 1950 - 1990) following their independence, both nations now find themselves, in the big picture of energy and resources, too late to the game. The solution is to learn to do more with much less energy, and do so quickly. Unfortunately, both nations' leaders feel the need to expend precious resources on "big power" displays such as blue water navies, space flights, etc. With a demographic storm brewing just over the horizon, they may soon find that prestige goods like aircraft carriers and vast submarine fleets are luxuries their nations can ill afford. The cliche is "It's all economics;" this can also be expressed as "follow the money," or "It's the economy, stupid." But the real story is: it's all Demographics. China's population is ageing rapidly as the 400 million-strong generation born in the 50s and 60s moves into retirement age. In the context of the war-torn generation before them and the smaller "one child per family" generation after them, this huge group of people forms a "pig in the python" demographic.  Their parents, impoverished by "The Great Leap Forward" and then The Cultural Revolution, could not save enough

to invest for their own retirement, let alone that of their offspring. Nor can the smaller generation of

current workers possibly produce enough to fund the retirement of 400 million elders and then save for their own

retirement.

Their parents, impoverished by "The Great Leap Forward" and then The Cultural Revolution, could not save enough

to invest for their own retirement, let alone that of their offspring. Nor can the smaller generation of

current workers possibly produce enough to fund the retirement of 400 million elders and then save for their own

retirement.

This demographic dilemma is one shared by much of the world, (link is to a U.N. report) including developed nations such as the U.S. Japan and the E.U., and other developing countries such as Mexico. Increased education and opportunity have led to lower birthrates, lower infant mortality and longer lives, all positive trends which exacerbate the problem now facing the global community: how can today's workers fund the retirement of so many elders? The short answer is: they can't. When retirement programs such as Social Security were established in the West (and in Japan after the war), the ratio of workers to retirees was on the order of 15 to 1, and lifespans were approximately 62 - 65 years. In other words, few people lived more than a few years beyond their retirement. The ratio of workers to retirees is slowly but inexorably dropping to an unsustainable 2 to 1 or even less in much of the developed world, even as average lifespans approach 80 years or more. This demographic crunch will be especially difficult in countries with low birthrates and minimal immigration, which includes Japan, Russia and much of Europe; the U.S. will fare a bit better due to high immigration and a somewhat higher birthrate. Although it isn't a popular topic, this guarantees that the social net so prized by the citizens of these nations will either collapse or change drastically to align with the reality of too many retirees and too few workers to support them. The problem is difficult enough for wealthy nations with productive infrastructures in place. It will be much worse for countries such as China with overwhelming infrastructure needs. China will be fortunate to find the capital and resources to clean up the nation's air and water, develop alternative energy sources and solve a host of other pressing economic and environmental problems (not to mention modernizing its huge military and other "big power" goals), much less fund the health care and retirement of 400 million elderly citizens.

China also faces a demographic found only in societies which favor males over females: a shortage of young women. Due to selective abortion and health care, the ratio at birth of boys to girls in China is 1.12. Thus there are 17 million more boys than girls (ages 0-14) in China. (according to the C.I.A. World Factbook). As a result, some men who might want to marry will be unable to find a mate, and factories which depend on cheap female labor from the countryside will find themselves short of workers. Such worker shortages are already being reported in the official Chinese press. The combination of poor air and water quality and an ageing population add up to huge demands for health care, even as the public health care system in China has been eroded by government budget constraints and moves to a market economy. While it's certainly possible to provide minimal health care benefits for such a vast population of the elderly, such a system would strain the resources of the wealthiest nations. Indeed, it is widely understood (if not publicly stated) that it's not the Social Security system which will bankrupt the U.S. government within the next 30 years, but Medicare (health care for the aged). China's rapidly growing population of elderly and its shortage of young workers will strain whatever social contract is currently in place, and make it more difficult for the central government to fund much-needed programs to build a sustainable economy. Here's another succinct summary of the demographic challenge China faces. There are other issues which will exacerbate the demographic and health care challenges: the trend toward starting families later, the health costs (in obesity, heart disease, etc.) associated with the higher fat diet and more sedentary lifestyle of the affluent young, and most painfully, perhaps, the burden placed on the offspring of single-child families as married couples must face caring for four elderly parents without the aid of siblings, aunts, uncles or cousins. Pensions based on large state-run businesses have evaporated as the state-run firms have been closed or sold off, and there is no money to replace them with a centrally funded, Social-Security type retirement system. Prior to the massive changes wrought by China's transition to a global economy, the average worker at a state-owned factory (which was of course all of them) could look forward to a modest pension. The state-owned firms often ran deficits, but then the central government shunted those deficits out of sight by guaranteeing loans to the factories from state-owned banks.

It was a closed system. Citizens with nowhere to spend or invest their money put their savings in a state-owned bank, which then lent this cash to the state-owned factories to cover their operating deficits, knowing full well that the loans (or even the interest) would never be paid. But as the inefficiencies of state-run companies ballooned, the deficits could no longer be covered by the sham loans. Saddled with an ever-mounting weight of non-performing loans, the banks required huge infusions of government capital just to appear solvent. In response, the central government began closing the money-losing state-owned factories, either shuttering them for good or auctioning them off to foreign banking consortiums for pennies on the dollar. Needless to say, the foreign banks refused to take on either the pensions or the tens of thousands of workers. It was not uncommon for a factory to have been squeezed down to 400 workers while the number of pensioners exceeded 10,000. The absence of a truly centralized pension system for retired workers is now haunting the nation. What seemed like a reasonable system in the 60s has crumbled, leaving the worst of both socialist and market-economy worlds: a failed socialist plan which has left millions of ageing workers with no pensions, and state banks burdened with hundreds of billions in bad debt, i.e. non-performing loans, which are inhibiting their transition to market economy lenders. This enormous mountain of bad debt--in typical fashion, no one really knows its full extent--has distorted the entire financial sector of the economy, setting it up for a potentially devastating decline or collapse. The Risks of a Financial Meltdown The seeds of af an investment bubble and subsequent financial meltdown are already in place. Although the Chinese economy is enormously complex, the primary danger can be summed up very simply: there is too much money pouring into the country to be wisely invested. As Japan so aptly proved circa 1989-90, too much money leads to a property bubble and subsequent crash (more obliquely known in some circles as a "hard landing"). The example of Japan is not a perfect analogy, of course, but it does show that such crashes can cripple a country for years or even decades. The flood of cash comes from multiple sources: The picture is complex, but the bottom line is: with gobs of cash to loan at low interest rates, China's banking system can't help but misallocate vast sums of money into failing firms and overheated sectors. Subsidized loans continue to go to failing state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and sectors such as real estate and steel which are prone to a boom-bust cycle of overinvestment and crash. Cheap and easy money feeds this cycle, because companies are operating in a world of such low interest that there is basically no cost of capital. The cost of this orgy of cheap borrowing is borne by savers drawing pathetically low interest on their money.

There are huge incentives for failing SOEs and other firms to "borrow their way" out of bankruptcy-- that is, to borrow enough money (at low interest rates) to fund their interest payments, and to expand their production to "produce their way to profitability." Of course if their competitors do the same, then prices fall and no one makes a profit--exactly what is happening in industry after industry in China: cell phones, televisions, etc. Such profligate loans to struggling companies benefit the government in two ways: they support employment of hungry workers, and they allow the government to put off the day of reckoning. That is, the day when the state banks have to truly write off all the non-performing loans (NPLs), not just the official total of $230 billion. The actual number is estimated to be twice that or even more--conservatively, $500 billion. To quote from Prof. Chun Chang's report for the Federal Reserve Bank "Progress and Peril in China's Modern Economy": According to some estimates, Chinese bad bank loans are as high as 40 percent of the nation's GDP. (For context, bad bank loans during the U.S. savings and loan crisis represented just 2 percent of U.S. GDP.) But SOCBs cannot force SOEs to pay back their loans—indeed, they've continued to lend to them—without causing their collapse and the inevitable political crisis that would ensue. (While the high level of nonperforming loans held by SOCBs would ordinarily lead to bank collapse, the pressure has been relieved to some degree by the monopoly that state banks hold on the savings deposits of Chinese households.)Why doesn't the government just "get it over with" and clean up the state banking sector once and for all? One reason is that the true liquidation of bad debt would wipe out the majority of its $600 billion horde of foreign reserves. Another is that the state has a creaky tax base. Unlike Western governments, China has an antiquated, confusing tax collection system; the vast majority of citizens pay nothing, and those who should pay have myriad ways to evade their fair share--cash accounting, bribing of officials, etc. Even though tax revenues have increased dramatically the past five years--even leading to articles entitled, "Is China Overtaxed?", tax revenues have fallen from 35% of gross domestic product in 1978 to 17%, while deficit spending is on the rise. As a result of corruption and the need to continue funding SOEs, the government has little choice but to keep the tottering system of bad debt afloat with more loans. It's a Hobson's Choice in a way--either tax the nation to pay off the accumulated half-trillion in bad debt (which was spent propping up state-owned companies), or keep the system afloat with more cheap and easy money in the hopes that whittling away the NPLs (non-performing loans) will overcome the system's underlying weakness. But the problem isn't just old debt--it's the lavishing of new bad debt. And since China's internal capital market is sheltered, there are no external market pressures to improve the loan portfolio or fundamentally change the structural incentives to make more bad loans. In a healthy financial system, the stock market provides an alternative form of financing for companies both new and established. Unfortunately, China's stock markets are "fixed" by the government, which owns 2/3 of the stock.

As a result, it's a fool's bet to buy stock in Chinese companies; if the government unloads even a part of its massive stock holdings, prices would immediately sink. The government was hoping, of course, for gullible investors to keep buying chunks of its companies for high prices, but the average Chinese investor has lost faith in such a rigged stock market. This failure to establish a fair and transparent stock market has another cost: new companies can't raise funds through IPOs as they can in the West. As a consequence, companies with legitimate need for new capital must turn to the banking system for money--the very system which favors state-owned firms and those with appropriate connections. As in Japan, many small firms are starved for capital while large companies have more money than they can efficiently invest. With money flowing so freely, the temptation is to invest it in "safe sectors" like property development. This herd mentality sets up a bubble in property valuations-- exactly what we're seeing worldwide, including China. It is certainly true that China's popluation of 1.2 billion can use another 100 million new housing units--but the question is, at what cost? The per capita income in China is still only $1,200 per year, compared to $40,000 in the U.S. While there's more than enough money to build a 100 million units of housing, are there enough people who can afford to buy them?  I personally know of middle-class people in China owning three apartments--one for themselves and two for investment.

These are not wealthy people, just folks with decent government or private sector jobs. Extrapolate that

number of "investment apartments" by millions, and you discern the outlines of a classic property bust:

everybody's into the game because "you can't lose" and "prices just keep going up every year."

I personally know of middle-class people in China owning three apartments--one for themselves and two for investment.

These are not wealthy people, just folks with decent government or private sector jobs. Extrapolate that

number of "investment apartments" by millions, and you discern the outlines of a classic property bust:

everybody's into the game because "you can't lose" and "prices just keep going up every year."

This sets up a boom in which housing and office towers are over-built, creating a supply which outstrips the demand of non-investor buyers. At some point a panic ensues (there can be any number of triggers), and some percentage of those vacant or rented apartments come on the market. Prices soften and then drop, causing worried investors to race to sell before the bottom drops out--causing, of course, the bottom to drop out. The key to this cycle is the unwavering confidence of the investor. Supreme confidence and easy credit always mark the top of any boom-bust cycle--and the world remains exceptionally euphoric about China's growth prospects. In China, however, many are fearful of such speculation and overinvestment; "Fears Rise Over Property Bubble." China's financial problems are not just of its own making. There are global forces at work which no government can entirely control. Indeed, China's flood of cheap capital can be traced back to the U.S. Federal Reserve's decision to blast away a regular business-cycle recession after 9/11 with basically unlimited liquidity and super-low interest rates. The Fed effectively exported these lows rates to the rest of our trading partners via this mechanism: mobile capital flows to the highest return, strengthening that nation's currency. Since none of the U.S. trading partners wanted a stronger currency, as that would stifle their exports to the U.S., everyone else cut their rates as well. (Those that didn't, such as South Africa, have seen their currency strengthen to painful levels.) All this "free money" triggered a housing boom in the U.S. (and in the rest of the world as well, except for Japan and Germany), enabling U.S. consumers to borrow money from their home equity to spend on consumer goods. Voila, the U.S. current account deficit (the trade deficit) with the rest of the world balloons to $660 billion, and the trade deficit with China suddenly doubles. And that's all China's fault, right? Not really. As certain members of the Fed never tire of repeating, the problem isn't hyper-active U.S. consumers but the surplus of savings around the world looking for a safe and profitable home. If their own country's growth prospects were good, then this capital would be invested at home. But alas, most of the world's economies labor under structural and political liabilities which have constricted their growth. As a result, money flows into the "safe," higher-growth economies: the U.S. and China.

These inflows of global capital have created the current imbalances. The money pouring into U.S. treasuries and other bonds funds our huge trade imbalance, while the money flooding into China fuels their manufacturing and property boom. All those manufactured goods flow to markets where growth is good, which at this point is the U.S. The big hullabaloo about China re-jiggering its currency peg is "much ado about nothing." Changing the yuan peg to the dollar will have little effect on the current account imbalance. The reasons are numerous. One is that many Chinese firms compete only with other Chinese firms, so the exchange rate adjustment won't boost U.S. competitors--they're aren't any. Where there are U.S. competitors, such as Motorola in cellphones, their competition are other multinationals such as Samsung and Nokia, who produce phones in China but price their globally marketed products (and pocket the profits) in other currencies. The benefits of this trade imbalance actually flow largely to U.S. corporations, not China. Have you ever wondered how U.S. corporations such as Wal-Mart can keep boosting their profits by 20% per year, year over year, despite mediocre sales increases? Or how is it that U.S. corporations are sitting on an unprecedented amount of cash (over $1 trillion and counting)? Do you think it has something to do with them paying Chinese workers $120 a month to manufacture many of their products, which they then market to the rest of the world (including you) at a hefty profit? The answer is yes. Many Chinese companies are squeezed by competition with their peers to the point that profits are low (2 to 4%) or non-existent. In the developing world, formidable obstacles stand in the way of companies attempting to become world-class multinationals-- including China. Successful global corporations require more than just hard workers and inexpensive capital; they must nurture, over decades of experience, deep managerial expertise and an obsession with quality. Currently, no Chinese corporations can yet match the managerial, manufacturing, marketing and R&D depth of a Sony, Toyota, Samsung, Mororola, IBM, Microsoft or Intel.  Most of China's exports are made for foreign companies, and the profits flow to these companies, not the

Chinese manufacturers. So before you buy into the argument that the U.S is the loser in the trade

imbalance with China, consider who's actually raking in the enormous profits.

Most of China's exports are made for foreign companies, and the profits flow to these companies, not the

Chinese manufacturers. So before you buy into the argument that the U.S is the loser in the trade

imbalance with China, consider who's actually raking in the enormous profits.

Recreating Silicon Valley isn't that easy, either. Silicon Valley is more than a cluster of buildings wired with fiber-optic cables. It is fundamentally a collaboration between research universities, entrepreneurs, venture capital and the U.S. government in which information flows freely because intellectual capital is vigorously protected by U.S. patent and trade law. Few developing nations can reproduce this precise mix--and so there remains one Silicon Valley and a number of small U.S. wannabes, and a bunch of half-empty business parks around the world with cheesy nicknames copycatting the phrase "Silicon X" (Alley, Triangle, Ditch, Jungle, Desert, etc.) Rather than view China and the U.S. as economic adversaries, it might be more accurate to see both nations as victims of their own successes. If China didn't have such a vast pool of hard workers and such a strong entrepreneural history and spirit, then perhaps it wouldn't be attracting such dangerously abundant global capital. And if other countries were growing at the same pace as the U.S., then the U.S. wouldn't be such a magnet for capital seeking a safe refuge. Everything you can say about China is true--and therein lies the difficulty. It's true that the central government is trying to clean up the banking sector, but it's also true that it's not doing so with any great success. It's true that environmental issues are being addressed, often quite successfully--but it's also true that many other ecological problems are languishing out of the spotlight. It's true that the majority of people are much better off in terms of material goods and opportunities--but it's also true that tens of millions are very poor (even in Shanghai many people make a living hauling rubbish in wooden pullcarts), and the basics such as clean air are beyond the reach of even the wealthy. The nouveau riche young sport expensive cellphones and walk away from banquet meals loaded with untouched food, flaunting a decadent excess certainly equal to any in the world; such wealth is the envy of the developing world. But if just breathing the air of your city is the equivalent of smoking two packs of unfiltered cigarets a day--is that wealth, or wealth squandered?  The Chinese culture has proven itself pragmatic and adaptable over the centuries--but its political leadership

has led it to near-ruin twice in the past fifty years. The central government is strong and vigorous enough to enact change, but

the corruption in its ranks obstructs fundamental improvements in efficiency and fairness.

The Chinese culture has proven itself pragmatic and adaptable over the centuries--but its political leadership

has led it to near-ruin twice in the past fifty years. The central government is strong and vigorous enough to enact change, but

the corruption in its ranks obstructs fundamental improvements in efficiency and fairness.

Every society can be viewed as an ecology of sorts--a complex interaction of history, tradition, ethics, religion, landscape, resources, military might, technology, trade, myths, art, politics, law and finance. Those societies which are rigid and ill-adapted to an era fail their people, while those still supple and adaptable find a way to overcome crises and reach new heights of opportunity and prosperity. Although some will say it is too early to tell--never mind the endless examples--rigid central planning and deeply corrupt societies have not fared well in our era. As the Soviets so effectively proved, you cannot steal your way to innovation or long-term prosperity, or distract your people with external enemies forever, or despoil your environment without permanent damage to your landscape and economy. You cannot place personal aggrandisement above the law without destroying people's faith in fair and just government. The path forward for China thus seems clear. Forces powerful enough to balance government excess and corruption must be nurtured: a largely free and open press and an independent judicial system. The press needn't be free to challenge the legitimacy of the Party, but it must be be free enough to scrutinize favoritism and root out abuses of the shared environment. Shouldn't the People be more important than any official? It seems an easy fit for Communist ideology. I know of no ideological reason why the Communist Party and central government couldn't foster these essential institutions within the existing power structure. The question, however, remains: can China's political structural impediments be overcome? Given the pervasive reach of corruption, it must be asked: perhaps the State isn't just corrupt; perhaps the State is corruption. If that turns out to be the case, then reform will remain purposefully ineffective; like a press which appears free but is not, the "reforms" may be only a simulacrum of change. It may well be that Party leaders are sincere about reform, but the nature of the Party and State precludes the type of deep transformation the nation's political structure so desperately needs to truly serve the people. It is not "China-bashing" to pose this question; indeed, no serious student of China (or Chinese history) can avoid the query, for there is no history of political oligarchies successfully reforming themselves from within. If the Chinese leadership is, as Orville Schell puts it, a "Mandarinate," and, as other books suggest, a Mandarinate not particularly interested in the views or concerns of the nation's citizenry, then such a transformation appears--at least from the long view of history--unlikely. Reform rises from bodies of government which reflect and embody the concerns of the common citizen, not the elite oligarchy; in the West, there are three such bodies: an unfettered, probing, even pugnacious press, the popularly elected legislature and the independent courts. (A trustworthy law enforcement arm is also necessary.) Only in such a widely representational system can the second-highest official in the F.B.I., an independent judiciary and a widely-distributed free press bring down a corrupt administration, and then change the balance of power in the legislative leadership. I refer of course to Watergate, the most serious attempt to corrupt the U.S. government in our country's history. Certain cultural issues overhang any sincere attempt at reforming corruption as well. The citizens of nations with a tightly controlled media quite naturally tend to think alike; in China, such uniformity of thought has been both a norm and a virtue. While the proliferation of environmental and other non-governmental groups in China reflect a growing diversity of opinion, the majority of citizens still respond in Pavlovian fashion to the State media's nationalism. Another pan-Asian cultural trait which inhibits national reform is the tendency to "mind your own business," which boils down to ignoring problems if they do not affect you or your family directly. This does not encourage common cause on regional or national concerns such as air pollution or water quality. A related pan-Asian cultural norm is to view the environment as a resource for human exploitation, and as a dumping ground. I can attest first-hand that rubbish and pollutants needlessly foul the beaches of Japan and the rivers and shorelines of Thailand and China. While some suggest that as nations grow wealthier, their environments grow cleaner, that was certainly not the case in the centrally-controlled Soviet republics. It would be false, then, to assume than rising wealth necessarily transforms a nation into an environmentally sensitive society. While prosperity may be one factor of many, it cannot replace cultural and educational transformation. The Illusion of Control The central government's primary concern is "stability"--but how much of China's future does the government and the Party truly control? Three areas may already be beyond the State's control: environmental degradation, the emergence of religion, especially Christianity, and the appeal of social protests. While one might assume that the central government has the power to change course midstream and radically change the culture of waste which has spoiled China's air, water and landscape. But Nature is a tangle of many feedback loops, many of which interact. Thus desertification, dropping water tables, dust storms and climate change are interconnected problems which may not be solved by planting windbreaks. Moving factories away from Beijing may reduce air pollution locally, but only at the cost of degrading the air elsewhere. Scrubbers can remove particulates from coal-fired power plants, but only if the catalytic elements are properly maintained and periodically replaced. Environmental transformation requires resolving two key structural deficiencies: accurate data must be collected and disseminated without political interference or editing, and regulations must be obeyed rather than skirted. In other words, the policies and regulations may be strict, but if the enforcement and data collection are not equally strict, the policies will inevitably fail. Environmental reform thus rests entirely on political reform. The spiritual hunger of a human populace should not be underestimated. The rise of "officially sanctioned" places of worship in China has been remarkable; while this appears to be a small part of Chinese national life at the moment, the growth of "informal" religious groups and gatherings, especially those under the Christian banner, are difficult to assess. While some in the U.S. hope for a religious transformation in China, others are confident that the Chinese culture is immune to fundamental spiritual change. Such slow cultural movements cannot be accurately predicted; it may be that the spiritual vacuum left by the demise of Communist ideology--what faith could survive the dual disasters of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution?--awaits filling by one religion or another. It was, after all, fear of such a spiritual force which led the Chinese Communist Party to evict all Christian missionaries, just as the Japanese Shogunate had done in 17th century Japan. The ubiquity of both spontaneous and organized social protests suggests such public dissatisfaction may already lay beyond the reach of the central government. Well-heeled condominium owners in Beijing know what to do when a developer threatens to block their view; they assemble a visible protest and demand results. Farmers too know what moves the authorities--a public protest which cannot be easily suppressed. It has been widely noted that the government may have unleashed a force which is now beyond their control in allowing (or encouraging) violent nationalistic protests and in succoring middle-class protests from property owners and nascent environmentalists. One essential to China's economic success is assuredly beyond any government's control: access and ownership of the resources required to support a billion people with middle-class aspirations. Though the Chinese government is securing petroleum assets wherever it can find them--unsavory African regimes such as Sudan top the list of its new oil-rich "friends"--the majority of the world's petroleum is controlled by the West or Mideast governments without natural or historical ties with China. Other resources such as iron ore lay in unstable countries in Africa or firmly Western nations such as Australia. China's courting of corrupt and venal African leaders is no different than Western nations' courting of corrupt and venal African leaders--but they have not yet discovered that such leaders have a habit of being overthrown. The tyrants' allies--in this case, China--often find that their influence wanes along with their friends' dictatorship. Indeed, great powers have been thrown out of smaller nations with alarming ease: the Soviets built the Aswan Dam, and what did they receive for their troubles? While any resource can be purchased on the open market, growing demand from China itself virtually guarantees that prices for the essentials of industrialization will rise along with demand. China is thus being forced to compete with other industrializing nations (India, Vietnam, etc.) and the wealthy West for the resources needed to fuel its spectacular growth. To meet the aspirations of its people, China will have to control or buy an enormous share of the world's natural resources. If, as appears likely (see above chart on the ecological footprint of humanity), there simply isn't enough for another billion middle-class folks, then the poorer citizens of China may find themselves priced out of the marketplace. What social and political repercussions that competition might spawn are unknown, but it is assuredly a challenge to the continued growth and stability of every nation--including China. 4/9/06: New link to an important article by Minxin Pei: "The dark side of China's dazzling economic boom: Hype conceals often sordid reality of government corruption and cronyism". The piece outlines the same themes which have been described at length above, and adds a incisive political analysis: the neo-Leninist central government has co-opted the intelligensia with plum positions and stipends, fending off the natural source of political reform. Such a neo-Leninist state must hold the levers of the economy in order to pass out the rewards and spoils which ensure loyalty or at least consent of the military, Party and other centers of power. In other words, there is a political limit to free enterprise in China which is not understood in the West. © copyright 2005-6 by charles hugh smith, all rights reserved in all media. If you found this essay of value, I would be honored if you linked it to your website or printed a copy for your own use. You may also enjoy my blog/wEssay page. or The Adventures of Daz and Alex: Stories of America. If you would like to publish this essay in another medium, or use an excerpt in another work, please email me for permission. Updated: April 9, 2006 |

||

|

|

home |