|

| articles | forbidden stories I-State Lines resources my hidden history reviews | home | ||

Writing/Film Dear Aspiring Writers: The Worst Advice You'll Ever Read A Literary Look at I-State Lines Spirited Away: Decay and Renewal An American Poem (Robinson Jeffers) Taoist Chinese Poems The Nelson Touch "It's all about oil, isn't it?" Kurosawa's High and Low A Bountiful Mutiny Howl's Moving Castle Thailand's Iron Ladies Trois Colours: Red The Thin Man: Thoroughly Modern Movies Why My Book Is Better Than the DaVinci Code 9 more in archive Recommended Books American Identity Hapas: The New America Can You Tell What I am? Part I Can You Tell What I am? Part II Only in America Self-Reliance Your Tattoo in 50 Years Cultural Commentaries On Hatred and Anti-Americanism Anti-Americanism Part 2 Anti-Americanism Part 3 French-Bashing Germany: We All Have Problems, But... Kroika! Chronicles This Blog Sells Out Doom and Gloom Sells The Kroika Mascot-"Auspicious Pet" Wal-Mart and Kroika Kroika and Starsbuck Take a Hit Kroika Ad 1 Kroika Ad 2 Kroika Ad 3 Kroika Ad 4 Kroika Makes Bid for Oreo (April 1) Unfolding Crises: Asia China: An Interim Report Shanghai Postcard 2004 Corruption and Avian Flu: China's Dynamic Duo Exporting the Real Estate Bubble to China Is the Bloom Off the China Rose? China Irony: Steel, Marx & Capital Curing The U.S. and China's Dysfunctional Relationship China and U.S. Inflation Trade with China: Making Out Like a Bandit 8 more Battle for the Soul of America Katrina, Vietnam, Iraq: National Purpose, National Sacrifice Is This a Nation at War? A Nation in Denial Why Is This Such a Tepid Time? That Price Isn't Cheap, It's Subsidized U.S. Fascists Seek Ban on Cancer Vaccine The Truth About Christmas American Dream or American Nightmare? The Most Hated Company in America 2006 Sea Change Obesity and Debt Immigration Ironies 10 more Financial Meltdown Watch What This Country Needs Is a... Good Recession Are We Entering the Next Age of Turmoil? Why Inflation Appears Low Doubling Down on 5-Card No-See-Um A Rickety Global House of Cards Are Japan and Germany Truly on the Mend? Unprecedented Risk 2 Could One Rogue Trader Bring Down the Market? Worried about Inflation? Stop Measuring It Economy Great? Bah, Humbug Huge Deficits and Huge Profits: Coincidence? Who's The Largest Exporter? Three Snapshots of the U.S. Economy Loaded for Bear Comparing Nasdaq to Depression-Era Dow Who's Buying Treasury Bonds? And Why? Derivatives: Wall Street Fiddles, Rome Smolders 31 more Planetary Meltdown Watch The Immensity of Global Warming Sun Sets on Skeptics of Global Warming Housing Bubble Watch Charting Unaffordability A Monster of a Housing Bubble A Coup de Grace to the Economy Hidden Costs of the Housing Bubble Housing Bubble? What Bubble? Housing Bubble II Housing Bubble III: Pop! Housing Market Slips Toward Cliff Housing Market Demographics Housing: Catching the Falling Knife Five Stages of the Housing Bubble Derailing the Property Tax Gravy Train Bubbling Property Taxes Have You Checked Your Property Taxes Recently? Housing Bubble: Where's the Bottom? Housing Bubble: Bottom II The Housing - Inflation Connection The Coming Foreclosure Nightmare 1 The Coming Foreclosure Nightmare 2 4 more Oil/Energy Crises Whither Oil? How much Is a Gallon of Gas Worth? The End of Cheap Oil Natural Gas, Naturally High Arab Oil Money and U.S. Treasuries: Quid Pro Quo? The C.I.A., Oil and the Wisdom of Crowds The Flutter of a Butterfly's Wings? A One-Two Punch to a Glass Jaw 2 more Outside the Box How to Make a Favicon Asian Emoticons In Memoriam: Winky Cosmos The Wheeled Vagabonds Geezer Rock Overload In a Humorous Vein If Only Writers Had Uniforms Opening the Kimono Happiness for Sale: Jank Coffee Ten Guaranteed Predictions for 2010 Why My Book Is Better Than the DaVinci Code Design Follies The New Jank Coffee Shop Jank Coffee, Upscale Tropic Style One-Word Titles Complacency Nostalgia Praxis Keys to Affordable Housing U.S. Conservation & China Steve Toma, Me & Skil 77s: 30 years of Labor Real Science in the Bolivian Forest Deforestation and Sustainable Forestry The Solar Economy (book) The Problem with Techno-Fixes I Love Technology, I Hate Technology How To Blow off Web Ads and More 2 more Health, Wealth & Demographics Beauty of the Augmented (Korean) Kind Demographics and War The Healthiest Cold Cereal: Surprise! 900 Miles to the Gallon Are Our Cities Making Us Fat? One Serving of Deception Is Obesity an Inflammatory Response? Demographics & National Bankruptcy The Decline of Europe: A Demographic Done Deal? Are the Risks of Obesity Overstated? Healthcare: Unaffordable Everywhere 1 more Landscapes Selling the Landscape The Downside of Density Building Heights and Arboral Roots Terroir: France & California L.A.: It's About Cheap Oil The Last Redwood Airport Walkabouts Nourishment The French Village Bakery Ideas What Is Happiness? Our Education System: a Factory Metaphor? Understanding Globalization: Braudel Can You Create Creativity? Do Average People Know More Than Their Leaders? On The Impermanence of Work Flattening the Knowledge Curve: The "Googling" Effect Human Bandwidth and Knowledge Iraqi Guangxi Splogs, Blogs and "News" "There is no alternative to being yourself" Is There a Cycle to War? Leisure, Time and Valentines Is the Web a Giant Copy Machine? History The Strolling Bones: Rock of Ages Bad Karma: Election Fraud 1960 Hiroshima: First Use All the Tea in China, All the Ginseng in America Friday Quiz Pet Obesity The Origins of Carbonara Organic Farms Oil and Renewable Energy Human Diseases Wine and Alzheimers Biggest Consumers of Chocolate 7 more Essential Books The Misbehavior of Markets Boiling Point (Global Warming) Our Stolen Future: How We Are Threatening Our Fertility, Intelligence and Survival How We Know What Isn't So Fewer: How the New Demography of Depopulation Will Shape Our Future The Coming Generational Storm: What You Need to Know about America's Economic Future The Third Chimpanzee: The Evolution and Future of the Human Animal The Future of Life Beyond Oil: The View from Hubbert's Peak The Party's Over: Oil, War and the Fate of Industrial Societies The Solar Economy: Renewable Energy for a Sustainable Global Future The Dollar Crisis: Causes, Consequences, Cures Running On Empty: How The Democratic and Republican Parties Are Bankrupting Our Future and What Americans Can Do About It Recommended Books More book reviews Archives: weblog April 2006 weblog March 2006 weblog February 2006 weblog January 2006 weblog December 2005 weblog November 2005 weblog October 2005 weblog September 2005 weblog August 2005 weblog July 2005 weblog June 2005 weblog May 2005 What's New, 2/03 - 5/05

|

May 31, 2006 Whither China?  Will China be hurt as the U.S. housing bubble bursts, triggering a recession? And why

should we care?

Will China be hurt as the U.S. housing bubble bursts, triggering a recession? And why

should we care?

We should care for a number of reasons, chiefly those of blatant self-interest. We depend on China (among others) to use their surplus dollars to buy our Treasury bonds (regardless of low yield and high risk of a decline) to keep our interest rates low. If the Chinese have fewer surplus dollars--i.e., our recession causes their exports to us to plummet-- then that also means they'll be buying fewer Treasuries. Once the willing buyers vanish, then interest rates will have to rise to entice less-willing buyers. And as everyone knows, higher interest rates mean higher mortgage rates, which will only speed up the global real estate bubble's collapse. There seems little doubt that China will be hurt by a U.S. recession. While some have argued that China's domestic market is large enough that they don't need exports, this view ignores two important factors of macro-economic growth: as Braudel documented in his massive three-volume history of capitalism, The Structures of Everyday Life (Volume 1 of Civilization & Capitalism)  On my first visit to China in 2000, the official English-language paper carried numerous

stories describing a massive over-capacity glut in domestic television production;

tremendous overproduction of TV sets had led to lower consumer prices and huge losses for

the producers. So yes, the Chinese can make goods for their domestic market, but they

can't sell them at a profit, for the reasons (ironically, perhaps) Marx outlined. As

this chart reveals, the Chinese are busily creating massive over-capacity in steel,

automobiles and many other key industries, aided by gigantic inflows of foreign capital.

On my first visit to China in 2000, the official English-language paper carried numerous

stories describing a massive over-capacity glut in domestic television production;

tremendous overproduction of TV sets had led to lower consumer prices and huge losses for

the producers. So yes, the Chinese can make goods for their domestic market, but they

can't sell them at a profit, for the reasons (ironically, perhaps) Marx outlined. As

this chart reveals, the Chinese are busily creating massive over-capacity in steel,

automobiles and many other key industries, aided by gigantic inflows of foreign capital.

For more, please read China Irony: Steel, Marx and Monopoly Capital. The other reason China needs Western partners is for capital. Up to 40% of their entire GDP is foreign investment--factories, high-rises, you name it. As the bursting housing bubble reduces American consumer's profligate borrowing and spending, then why would anyone pour additional billions into making new factories in China? Once foreign investment dries up, so will the Chinese sectors which depend on huge inflows of foreign capital. As for the Chinese real estate market: sadly, the rest of the world exported their bubble to China. Experienced analyst Andy Xie expects a hard landing in China properties values, and there is little evidence that the government is successfully reining in the vast speculative building of luxury properties. The problem is structural; while the central government is theoretically in charge of everything, the actual administration is left in the hands of local authorities-- the same authorities who are beholden to growth at any price and who are famously corrupt. The consequence is that central government policies are rarely enforced, in either economic or environmental policies. So the government announces yet another Yangtze River clean-up campaign but few expect any real action to result because the clean-up depends on local authorities with other things on their minds--such as getting rich and enabling their region to get rich.  The structural flaw in the Chinese financial system relates not to local authority but

the peculiar way the government has funded employment. Rather than tax productive assets

and people, China has funded its notoriously money-losing government factories by taking

the savings of its citizenry and lending that money to the factories through its four

State-owned banks. As the factories

continue to lose money, new loans are made; the alternative is to close the factories and

suffer mass unemployment, which has occurred in the industrial north. Despite such large-scale

lay-offs, about 40% of the workforce still labors for a government-owned enterprise.

The structural flaw in the Chinese financial system relates not to local authority but

the peculiar way the government has funded employment. Rather than tax productive assets

and people, China has funded its notoriously money-losing government factories by taking

the savings of its citizenry and lending that money to the factories through its four

State-owned banks. As the factories

continue to lose money, new loans are made; the alternative is to close the factories and

suffer mass unemployment, which has occurred in the industrial north. Despite such large-scale

lay-offs, about 40% of the workforce still labors for a government-owned enterprise.

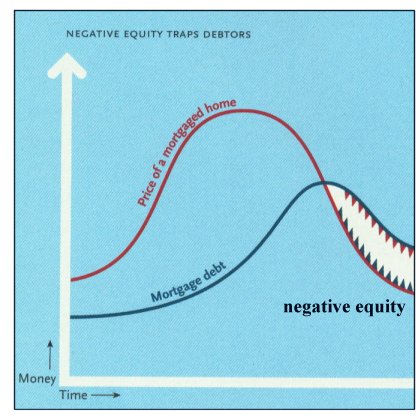

Factories that remain open are still drawing new loans which will never be paid back; and what's left of the closed factories is hundreds of billions in bad debt. The government throws $50 billion or so to reduce the debt every now and again, but this doesn't reform the system; it just keeps the still-growing bad debt down to managable levels. As China shifts to a system of tax collection, they might be able to wean themselves off this bizarre system of loaning savings out, never to be repaid, in lieu of public spending; but the tax collection system is young and already corrupted; some pay, most don't. A recent estimate of China's bad debt at $919 billion drew a chilly official response and was promptly withdrawn-- excellent evidence that it was accurate or perhaps even low: China's bad debts. The reason is, of course, that the Chinese government is very much into managing perceptions; this plays out in myriad ways, such as ignoring the cultural revolution as an embarrassment (like bad debt) better left obscured from public scrutiny. If everything which doesn't fit into the official propaganda is suppressed, then how can anyone be confident that bad debt, or indeed, any data, is even close to reality? And if you don't have any real data, how can you make good decisions? That doesn't bode well for either the Chinese government or the foreign investors gambling on its officially burnished future. For more on these topics, please read China and the U.S.: Curing a Dysfunctional Fiscal Relationship and China: An Interim Report: Its Economy, Ecology and Future. May 30, 2006 The Growing Financial Risks of the Housing Bubble  This is not your father's housing market or indeed, his mortgage market. The imbalances,

and thus the risks, of the housing bubble have spread into our entire financial system.

This is not your father's housing market or indeed, his mortgage market. The imbalances,

and thus the risks, of the housing bubble have spread into our entire financial system.

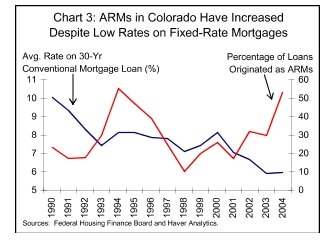

How so? Let's start--and end--with mortgages, leverage, derivatives and debt. First up is the chart showing that mortgages have grown to about 2/3 of banks' total credit portfolios. Note how this is up from less than 30% twenty years ago. This isn't just a measure of their mortgage exposure; it's also a measure of their exposure to risk in the credit market should a decline in the housing market trigger a rise in non-performing loans--i.e., people squeezed by ARM re-sets or rising debt loads to the point they are unable to keep current on their mortgage payments.  A very knowledgeable reader who prefers to remain anonymous recently encapsulated some of

the other risks inherent in the current housing and lending markets. His first point: the extreme

downside risk inherent in highly leveraged real estate:

A very knowledgeable reader who prefers to remain anonymous recently encapsulated some of

the other risks inherent in the current housing and lending markets. His first point: the extreme

downside risk inherent in highly leveraged real estate:

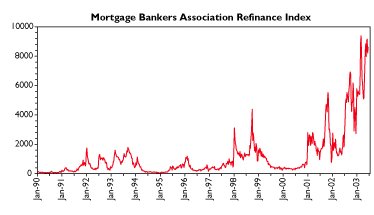

Your recent posting about the significance of a 10% decline is certainly right on the mark. What's interesting is that people don't think about the fact that in the stock market 10% volatility is nothing, but that's because margin accounts limit leverage of retail investors to 50%. In the housing bubble, 10% volatility is HUGE because there are so many investors leveraged to 100% (or more). Even those without interest only or negative amortization loans who HELOC'd (home equity line of credit) are at huge risk, especially since home equity is such a large part of people's retirement plans.This contributor noted the psychological impact of the tax policy which rewards people for flipping their primary residence every few years--and the rise of mortgage-backed securities and derivatives: Another topic of interest I don't see get much press as a driver of the housing bubble relates to the tax free treatment of the first $250K or $500K in gains on a primary residence. Although there's much press on how our government spurred the housing bubble with a liquidity bail out based on money supply and cuts in interest rates, I think the effect of these tax credits are hugely underestimated in terms of a wholesale change in American "investment psychology". An additional driver I would suggest which also gets little press is the massive proliferation of derivatives by financial institutions to off load and disperse mortgage loan risk and the lax regulatory environment promoted by the prior and current Fed.  A bit of history is necessary here. In the good old days, local banks would actually

retain the mortgages they underwrote, collecting the interest and principal as an integral

part of their portfolio of assets and their income stream. This is now as quaint as buggy

whips. Lenders quickly sell any mortages they underwrite to large banks which just as quickly

aggregate hundreds of millions of dollars of mortgages into "mortgage backed securities"--in

effect, turning mortgages into securities which can be traded like bonds. As the

chart reveals, this practise exploded in 2000.

A bit of history is necessary here. In the good old days, local banks would actually

retain the mortgages they underwrote, collecting the interest and principal as an integral

part of their portfolio of assets and their income stream. This is now as quaint as buggy

whips. Lenders quickly sell any mortages they underwrite to large banks which just as quickly

aggregate hundreds of millions of dollars of mortgages into "mortgage backed securities"--in

effect, turning mortgages into securities which can be traded like bonds. As the

chart reveals, this practise exploded in 2000.

And like bonds, the securities can be tranched into various chunks of risk and hedged by various types of derivatives. The idea, of course, is to minimize risk by hedging with derivatives--but the explosion of derivatives has put risk management in uncharted waters. As my correspondent explains:

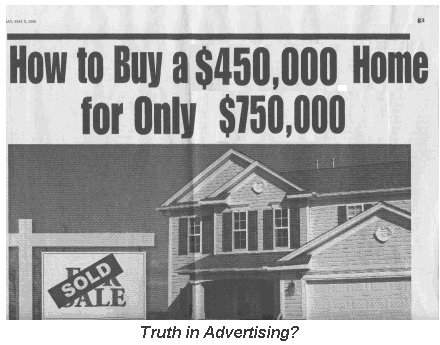

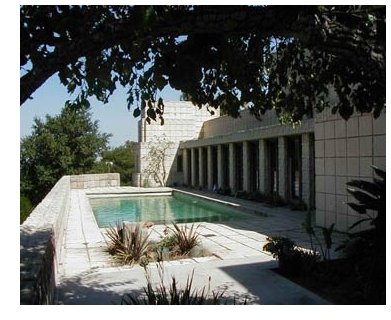

Regarding mortgage backed securities, just to be clear, there seem to be two related issues:Well said, well said. May 29, 2006 Truth in Advertising--Buying a $450K Home for $750K

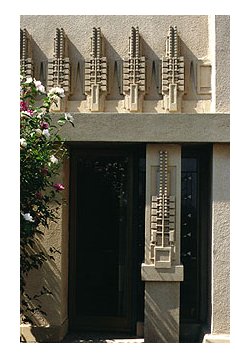

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * I recently came across this ad in a major American newspaper and was struck by the "truth in advertising" which was apparently imposed on a typical real estate pitch aimed at the naive and greedy (as opposed to the experienced and greedy). The ad went on to list "The cutting-edge secrets to buying real estate at 30% to 50% above market value:" Low and behold, all the conditions have been met, and it is indeed possible to buy houses for 50% above their market value. Of course when inflation can no longer be cloaked, it will be too late to stop its further ascent--which insures mortgage rates will climb, bankrupting all those with adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs). The massive over-supply of investor-owned units is already raising inventories around the nation, and as this trickle gorws to a mighty flood, the foreclosures of the ARM-bankrupted will also hit the markets. As lenders are inundated with losses from risky loans gone bad (surprise, sub-prime borrowers are not good risks), they will no longer be able to lend money as their reserves will have to be rebuilt even as their losses multiply. Leverage will fall off a cliff as lending standards are belatedly raised, but alas, all this will be too little, too late; the over-supply has been built, the demand has been sated, and investor-owned properties will soon be on the market. The cutting-edge secret to buying real estate at 30% to 50% below market value? It's this simple: wait a few years for the market to re-set valuations. Pretty simple, huh? Congratulations to reader Robert C. for correctly identifying yesterday's image as Taliesin West, Frank Lloyd Wright's home and studio in Scottsdale, Arizona. His (very) modest prize: a signed copy of I-State Lines. May 27, 2006 The American House and Frank Lloyd Wright  Frank Lloyd Wright did not design a housing "style;" he designed a new American identity

rooted in a landscape of democracy. In the current obsession with housing as an

investment vehicle and a ticket to gobs of free money, it's worth recalling that a house

is not just a repository of cash value or even shelter; it is also a space which nurtures or

deadens identity and either wastes or employs limited resources. Wright understood this in

a way which has largely been lost in our design-deprived era.

Frank Lloyd Wright did not design a housing "style;" he designed a new American identity

rooted in a landscape of democracy. In the current obsession with housing as an

investment vehicle and a ticket to gobs of free money, it's worth recalling that a house

is not just a repository of cash value or even shelter; it is also a space which nurtures or

deadens identity and either wastes or employs limited resources. Wright understood this in

a way which has largely been lost in our design-deprived era.

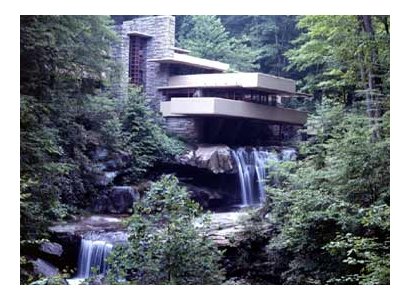

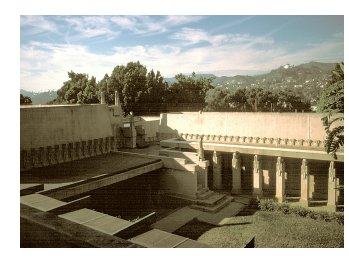

Like many other larger-than-life people, Wright was a mass of sometimes prickly or even unlikeable contradictions. Known for an almost comically monstrous ego, he nonetheless produced a body of work and a philosophy which is uniquely American in vigor, scope and depth. How egotistical, you ask? A young couple once wrote to Wright, inquiring about the cost of his services. They heard nothing for months and then received a call one day from an imperious-sounding male: "This is your architect speaking." It was pure Wright; never mind responding to the inquiry about costs; my schedule (and bank account) has been cleared, and I will now design your house, regardless of your wishes.  History has not always been kind to his buildings, either; many leak or suffer structural

problems; the

Ennis House (shown above) in the Los Feliz district of Los Angeles is in the midst of a multi-million dollar

structural rehab, and

Falling Water, perhaps Wright's most famous house, recently underwent a complex

structural renovation.

History has not always been kind to his buildings, either; many leak or suffer structural

problems; the

Ennis House (shown above) in the Los Feliz district of Los Angeles is in the midst of a multi-million dollar

structural rehab, and

Falling Water, perhaps Wright's most famous house, recently underwent a complex

structural renovation.

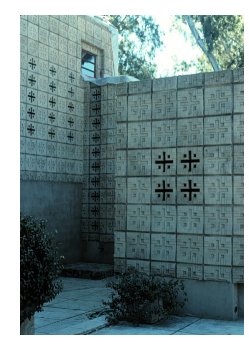

Given that these homes were designed and built in the 20s and 30s, before structural engineers fully understood how to calculate all the forces placed on buildings, it may be unfair to place the blame entirely on Wright's unconventional designs and construction techniques. Still, it is fair to say that his smaller, more conventionally constructed "Usonian" houses have not required the enormously expensive repairs which have plagued some of his larger, stretching-the-envelope projects.  Wright was dedicated not just to large-scale projects for wealthy clients but to a vision

of affordable, beautifully designed homes for average-income people, houses he dubbed

"Usonian" (a derivative of "U.S."). As a result, he experimented at great length with cheap,

easy-to-build materials, most notably concrete blocks, as shown here in a wall of his

La Miniatura house in Pasadena, California.

Wright was dedicated not just to large-scale projects for wealthy clients but to a vision

of affordable, beautifully designed homes for average-income people, houses he dubbed

"Usonian" (a derivative of "U.S."). As a result, he experimented at great length with cheap,

easy-to-build materials, most notably concrete blocks, as shown here in a wall of his

La Miniatura house in Pasadena, California.

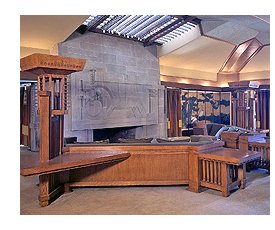

One of my favorite Wright stories is his own account of discovering that ancient Chinese and Japanese artists had developed the tenets of his "organic architecture" long before he himself set pen to paper. This degradation of his genius sent Wright into a deep funk until the happy thought occurred to him that as these past masters were not alive today, he was still the world's premier torch-carrier of "organic" design. What is "organic" architecture? Simply put, it is buildings which are integrated into, and draw inspiration from, the landscape in which they are sited. Further, the home's furnishings are designed into the house itself rather than purchased willy-nilly or changed out every few years as fashion dictates.  Here is an example from the Hollyhock House in Los Angeles. One of the charming features of

this living room is the small stream of water which meanders around the fireplace. On my

last visit some years ago, the rivulet of water was not running, but the concept was

dramatically and invitingly original.

Here is an example from the Hollyhock House in Los Angeles. One of the charming features of

this living room is the small stream of water which meanders around the fireplace. On my

last visit some years ago, the rivulet of water was not running, but the concept was

dramatically and invitingly original.

I cannot quite describe the profound influence these buildings had on me as a child. Can you vividly recall any houses you visited as a child? Can you relive the sense of awe and wonderment you felt? Did any house evoke such a powerful sense of mystery in you that the memory still burns hot in your mind? This is the largely unrealized power of great design; just entering a Wright house, especially a small Usonian one, is to feel welcomed and spiritually enlivened in a way which is incomprehensible to those who have known only bland, drywall-stucco-pressed sawdust-siding monstrosities. This is not an intellectual experience; it is a deeply emotional, visceral one which transforms your understanding of space and the great unrealized potential of housing to uplift the human spirit.  We lived in the Los Feliz area for several years in my childhood, and I would often gaze

up at the low, almost brooding Mayan fortress of the Ennis House. My elementary school

was located just below the

Hollyhock House, and my summer art classes

were held in the property's small guest house (circa 1963-64). As a 10-year old, I did not know about Wright,

or what made these buildings so memorably mysterious and attractive; but the buildings

work their magic perhaps more readily on children than on jaded (or more accurately, brainwashed)

adults.

We lived in the Los Feliz area for several years in my childhood, and I would often gaze

up at the low, almost brooding Mayan fortress of the Ennis House. My elementary school

was located just below the

Hollyhock House, and my summer art classes

were held in the property's small guest house (circa 1963-64). As a 10-year old, I did not know about Wright,

or what made these buildings so memorably mysterious and attractive; but the buildings

work their magic perhaps more readily on children than on jaded (or more accurately, brainwashed)

adults.

If you are not familiar with Wright's Usonian concept, then scroll through

Matt Taylor's excellent site on Usonian houses. To quote just one paragraph:

If you are not familiar with Wright's Usonian concept, then scroll through

Matt Taylor's excellent site on Usonian houses. To quote just one paragraph:

"One comment that Mr. Wright made again and again was 'until we have an organic culture we will never have an organic architecture.' His point is that architecture is the result of the choices individuals make and it expresses the culture they make up and in turn are influenced by. The Usonian house is not just another way to “style” a building - it is about a different way of living; a way that, today, is alien to the mainstream of our American culture. The usonian way is about relating differently to the Earth, to life and to all living beings - it is an integrated, natural life-style. Sustainable, evolving, sensory, engaging - it is to be surrounded by beauty and to live in harmony."To step into a Usonian house--small, inexpensively constructed of basic materials--is to understand how far we have drifted from being a sustainable, spiritually enriching society, and how distant the McMansions and subdivisions of today are from the profoundly democratic and practical vision made real in Wright's Usonian homes. May 26, 2006 Where Is This?  Today's location, like my little novel

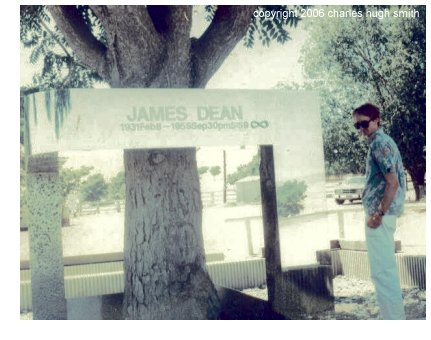

Today's location, like my little novel I-State Lines, is about finding one's identity within the American landscape. Like the person who designed the structure in this photo, and my protagonist Daz, I too sense a deeply enervating falseness in the standard American landscape of bloviated, pretentious McMansions with fake columns built of fake materials and inauthentic shantytown malls designed to create a false world of consumer desires. Between the cellphones glued to passengers' ears and the TV screens in the minivans, and the cooled-cocoon interiors of identical fast-food and mall outlets, the disconnect between the typical American citizen and the American landscape seems almost complete. Although it is not widely remarked upon, we humans form what can only be described as a spiritual identity with our landscape; and to the degree that we lose touch with that landscape and live in buildings utterly detached from any sense of the land they rest on, then we become, regardless of our religious faith, spiritually bereft. A novel which describes the deep relationship we establish with the landscape we live in happens (perhaps not by chance) to be one of my favorite books: The Enigma of Arrival In the U.S., I think this "siting of the soul" can be illustrated by stories of people raised on the Great Plains who find the presence of mountains disturbing. In a similar fashion, mountain-dwellers may feel out of sorts in a big-sky prairie landscape. For me, the touchstone is the Pacific Ocean. Although I have lived beyond visual range of the Pacific at times, I cannot imagine being more than a few miles from that limitless expanse of sea. For other Americans, it might be wetlands, or a river or a lake or broken canyonland or tidy orchards; but each of us locates our deepest identity within an American landscape. Now that graduation season is upon us, please consider giving a copy of my little book or Naipaul's wonderful novel (or both) to the graduates on your list. Sure, I want the sales. (Big deal, a $1 a copy; I could do better on a street corner with a tin cup.) But more important than that is the theme of the book, which is exploring the American landscape as part of the process of finding one's life work and one's identity. How does this relate to graduation? Here's what an independent bookseller, Keri Holmes, had to say about I-State Lines: "The story works on so many levels, it's hard to summarize. Summer vacationers looking for a "Road Trip" story won't be disappointed. High School and College juniors and seniors pondering their next steps will be inspired."You can order the book from Ms. Holmes' bookstore, The Kaleidoscope: Our Focus Is You which happens to be in Iowa. Though physically sited at 112 1st Avenue NW, Hampton, IA 50441 (Tel: 641-456-2787, Fax: 641-456-2809) it is available to you via the miracle of the Internet. (Shipping is free on all orders, and you can't beat that.) Or if you have an open order at amazon.com, you can of course add I-State Lines Be the first to identify the locale behind me, and I'll send you a collector's copy of my book I-State Lines. So email me! We have two winners! Emilio G. and Dan S. correctly identified the Friday "mystery park" as the Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park in the Colorado Rockies. Congratulations, Emilio and Dan! A signed copy of I-State Lines will go to each of you. May 25, 2006 Inflation and Housing: Calculating the Bust  Astute reader Richard C. was kind enough to send me a link to UCLA economist

Christopher Thornberg's talk on the California housing bubble.

Astute reader Richard C. was kind enough to send me a link to UCLA economist

Christopher Thornberg's talk on the California housing bubble.

Richard described the program thusly: "Although a bit long to watch in the front of the computer (58 minutes), Thornberg's talk is a tour de force performance by a mainstream economist." I heartily concur. So what are Thornberg's conclusions? His best-case scenario: no appreciation in housing through 2011 or 2012. In other words, the house that sold in 2005 at the top for $400,000 will still be worth $400,000 in 2012. Well, you sigh; that's not too bad, right? At least they're not losing money. Alas, if only it were true. At the very modest rate of 4% inflation, the $400K house will decline to $301,000 in real dollars. Although I drew a straight line for simplicity's sake, the calculations were not straight-line. Here are the annual values after the 4% inflationary haircut: 2005: $400,000 2006: $384,000 2007: $369,000 2008: $354,000 2009: $340,000 2010: $326,600 2011: $$313,600 2012: $301,000 You might reasonably ask: if wages are keeping pace with inflation, and interest rates remain low, why wouldn't housing rise with inflation? Thornberg's answers: 1. the U.S. and yes, even California, has experienced massive overbuilding; the number of homes built has far exceeded the growth of households. This overhang will suppress prices for at least six years. 2. The end of the bubble will cause massive job losses in the very categories which have propped up the economy: building, financing and furnishing millions of new or rehabbed houses. These job losses will knock the job-prop out from under housing values. And as everyone knows, housing declines when jobs disappear. So that's why this is a best-case scenario; a worst-case scenario would be a 25% nominal decline plus the 25% real-dollar decline due to inflation. Watch the presentation, look at his charts and prepare to accept the realities he documents. OK, so the homeowner is down 25% by 2012; that's not too bad, right? But wait--we forgot about subtracting the costs of ownership and the opportunity cost. As readers have pointed out, I have under-estimated both the opportunity cost (the cost of leaving a down payment sitting in a depreciating house rather than in, say, high-yield corporate bonds paying 6% annually) and in the cost of ownership above and beyond the rental price of the same house in the same neighborhood. The proprietor of the excellent View From Silicon Valley blog wrote to explain how I had likely over-estimated the tax benefits of a mortgage deduction and under-estimated the property tax costs of owning compared to renting. In a previous example regarding a hypothetical $400,000 house purchased in 2005 with 20% down and a conventional 30-year fixed-rate mortgage of 6%, I had estimated the value of the tax write-off of mortgage interest at $6,000 and the annual net loss in owning compared to renting at $6,000. "View From Silicon Valley" noted: This ignores the standard deduction. (I think it's now close to $10K for married tax filers?) Thus, the net savings on taxes may be zero, depending on other deductions. (Admittedly, even a moderately sophisticated buyer --one who actually does the math and is depending on the mortgage interest deduction to make the buy decision work-- probably has other deductions.)Another knowledgeable reader, Wayne D., describes the opportunity costs of owning a house, and provides a careful analysis of the costs of renting vs. owning: A small, but significant point left out of your analysis is the opportunity cost lost of the $80K (down payment). That's about $4K per year at 5% interest, which should be put into any equation evaluating losses. That increases their total losses because the $80K, of course, was tied up in a losing investment when it could have been earning interest.To summarize: if the buyer of a $400,000 house in 2005 had taken a conventional mortgage of 80% and made a 20% down payment, then we have to figure the opportunity cost of that $80,000 which is "dead money" in a non-appreciating real estate market. At a very modest 5%, (you can get 6% or even 7% nowadays), the homeowner's $80,000 cash would grow to about $113,000 by 2012--a total of $33,000 in lost income they could have earned had they rented rather than owned. Given the complexities of calculating the tax benefits of mortgage interest (about $19,000 in our hypothetical example of a $320,000 fixed-rate 30-year mortgage at 6%--check calculator at MSN Money yourself to confirm) and the local costs of property taxes and insurance, I believe an estimate that it costs $500 more per month to own a $400,000 house than it does to rent an equivalent home is conservative; in much of the nation, I think $1,000 a month would be a more accurate number. This conservative $6,000 "annual cost of owning" works out to a net loss of cash in the household by 2012 of $42,000--more, of course, if that $6,000 had been placed in an account drawing 5% interest. Added to the $33,00 in opportunity cost, this household would be $75,000 poorer by 2012 than a family which had rented for those seven years. In terms of a family balance sheet, the renting family is $75,000 richer and the homeowning family is $75,000 poorer. In terms of assets and liabilities, we could deduct this loss against the family's assets--i.e. the $400,000 house. The point is simple: without significant annual appreciation, owning a house which was purchased 2004-2005 makes poor financial sense. If there isn't annual appreciation above and beyond inflation, then owning a house is, in a strictly financial sense, a bust. May 24, 2006 Running Out Of Oil Versus Running Out of Cheap Oil  The Atlantic's senior editor Clive Crook summarized the Standard Line on oil

and energy very succinctly in the June issue:

The Atlantic's senior editor Clive Crook summarized the Standard Line on oil

and energy very succinctly in the June issue:

Much of the rhetoric about oil is overheated. The world is not running out of the stuff. With present technologies, proven and probable reserves of oil wil be sufficient for decades ... an array of existing but not widely applied technologies would make it economically feasible to extract oil from tar sands or shale, or to convert coal to liquid fuel.While Mr. Crook reaches the right conclusions in his piece, "Shock Absorption"-- he calls for energy diversification and a long-term "fix" to global warming--his grasp of petroleum realities is weak. To wit: virtually the entire substance of the above quote is utter nonsense. While Mr. Crook is no doubt a very smart guy, and his long-term view is worthy, he obviously didn't bother reading anything of value about the oil industry before he penned his breezy opinions. The realities are rather different than his opinions:

I could go on, but I'm getting tired of typing the almost limitless errors behind Mr. Crook's blithe opinions. Better for you to read Beyond Oil: The View from Hubbert's Peak. What Mr. Crook fails to divulge is that the global economy has been relying not only on oil per se, but on extremely cheap-to-pump-and-refine oil, the oil which has gushed unbidden from a handful of supergiant fields which are rapidly being depleted. Yes, there is "plenty of oil in the ground," Mr. Crook, but much of it cannot be extracted, and the rest can only be extracted at great expense. While Mr. Crook is pleased to note that the U.S. economy has withstood the effects of $50/barrel oil with no ill effects (or at least none that are visible in "official" statistics), does his hubris extend to $100/barrel or even $200/barrel oil? You know, the kind that's still left in the ground? Mr. Crook's ignorance is not just stupendously absymal, it is willful and therefore inexcusable in the age of the Web search. I also wonder if Mr. Crook would be so smarmily confident in the ease with which oil will flow to the tanks of airliners and vehicles if he lived in, say, West Virginia, near the coal strip mines he so cheerily assumes will provide him with gasoline, or the square miles of Canadian tundra being torn up and destroyed for his "economical" tar-sands oil "fix." I am rather confident that Mr.Crook resides in the safe and clean cocoon of the Upper West Side or an equivalent haven of the well-heeled--the very population who would not be too bothered by high energy costs. Sadly, Mr. Crook printed his utterly irresponsible opinions without the slightest shred of research or knowledge. Too bad he wasted such a widely read media forum for unsupported rubbish which only furthers the American public's profound ignorance of the energy complex which fuels their soon-to-be-very-expensive lifestyle. May 23, 2006 U.S. Healthcare: Working Toward a Real Solution  As this chart so chillingly illustrates, healthcare as currently configured in this

country will drive us into national bankruptcy. (All that future Federal spending

is largely Medicare and Medicaid.) We as a nation need a solution soon--

and not a solution delivered by poo-bahs in think tanks or the healthcare lobby

(oops I meant to say "Congress"), but a solution which can be understaood and embraced by

those who will have to live with it, i.e. us, the citizenry.

As this chart so chillingly illustrates, healthcare as currently configured in this

country will drive us into national bankruptcy. (All that future Federal spending

is largely Medicare and Medicaid.) We as a nation need a solution soon--

and not a solution delivered by poo-bahs in think tanks or the healthcare lobby

(oops I meant to say "Congress"), but a solution which can be understaood and embraced by

those who will have to live with it, i.e. us, the citizenry.

Just to cover how bad off we are as a nation, consider these data points: we spend more on healthcare per capita than any other nation, fully 15% of our stupendous $12 trillion GDP, and yet we are far less healthy than the populace of England, which toils under a parsimonious rationed-care national system: Middle-aged Americans are puzzlingly sicker than their English counterparts (from The Economist).  As if paying a fortune to be in poor health isn't bad enough,

the Census Bureau counts 45 million uninsured, and a recent Commonwealth Fund study found

41% of moderate- to middle-income adults did not have health insurance for at least part of

2005, up from 28% in 2001. A Harvard University study found medical bills were a factor in

half of consumer bankruptcies.

As if paying a fortune to be in poor health isn't bad enough,

the Census Bureau counts 45 million uninsured, and a recent Commonwealth Fund study found

41% of moderate- to middle-income adults did not have health insurance for at least part of

2005, up from 28% in 2001. A Harvard University study found medical bills were a factor in

half of consumer bankruptcies.

To sum up: you couldn't design a worse system than ours if you tried. Millions uninsured, hundreds of billions wasted in paperwork, fraud and needless "care," and after spending $2 trillion on healthcare, we're significantly less healthy than our counterparts elsewhere. Where do you even start in designing a solution? I turn to Charles Ruland, an astute reader with a frontline understanding of our current system, for a knowledgeable and very sensible outline of a national healthcare plan which wouldn't bankrupt us and which would undoubtedly provide better, more efficient care to all our citizenry than our current mess of a system. So please read on. (I have added occasional bolding for emphasis) Your question about the "best solution" to our long-term health care cost dilemma...aaah, now you are asking me to tame a monster! But I have a few opinions. Here goes.Does this plan make sense to you? It certainly does to me. Thank you, Charles, for an in-depth and very thoughtful presentation of a workable national healthcare plan which people might actually accept. Once we get the uninsured / minimum coverage problem resolved, we can tackle the equally divisive issue of improving the actual care. For a primer of how poorly we're faring in terms of care, read BusinessWeek's lead article, "Medical Guesswork: From heart surgery to prostate care, the health industry knows little about which common treatments really work." Sobering reading, indeed. May 22, 2006 Housing: 10% Decline May Trigger Financial Ruin Astute reader Bob Decker wrote: Many people don't seem to understand that if you put $100,000 down on a million dollar house . . . and the market drops just 10% . . .you lost your $100,000 of savings/equity and may not ever see it again.  If you need evidence that prices are falling, consider this USA-Today story,

median prices fall, just one of many media stories documenting

the decline in both new and existing home prices.

If you need evidence that prices are falling, consider this USA-Today story,

median prices fall, just one of many media stories documenting

the decline in both new and existing home prices.

Let's take Bob's point and extrapolate it a bit. Consider a family which bought a home for $400,000 at last year's market top, and now for one reason or another find they have to sell: someone lost a job, got transferred, developed a chronic medical condition, etc. In many markets, they will find that the values in their neighborhood and price range have already dropped; in areas such as greater Boston, a 10% decline appears to be common. Let's assume that the family was one of the rare home buyers who took out a conventional mortgage, with 20% down payment in cash and a loan balance of 80%. (As documented here earlier, up to 60% of recent home buyers have selected no down, interest-only loans.) So let's do the math, given a 10% decline in values since they bought: Now, on the sale:

Let's be frank: this poor family which started out with a solid $80,000 and 20% down, has essentially been wiped out by a "mere" 10% decline in housing values, once actual transaction and ownership expenses are accounted for. As for those new homeowners who bought with no money down, this example shows that the transaction fees alone will drive them into bankruptcy, even if they sold the house for their original purchase price. As this chart of the San Diego market illustrates, the number of homeowners exposed to rising mortgage payments is over 2/3 of recent buyers. Combine this with the large number of people who bought homes with no money down, and you get a fuller picture of the damage which will be wrought by a "mere" 10% decline in housing values in an era of rising mortgage rates and "resets" of ARMs to much higher rates. (According to the National Association of Realtors, the median first-time home buyer's deposit last year was just 2% of the price, while 43% of first-timers put down nothing.) Thank you, Bob, for making this all-too-easy to forget point about leverage: works great in a rising market, not so great in a declining market. May 20, 2006 Waimea Canyon Connection? I received a number of good guesses about yesterday's "where is this?" quiz--the Snake River canyon, Zion, Bryce, Copper Canyon in Mexico--and while it certainly bears a strong resemblance to some of those wonderful sights, this canyon is elsewhere in the continental U.S. A more distant park--Waimea Canyon on the island of Kauai, Hawaii--drew one guess and one intriguing mystery. My friend and Ka'a'awa photographer / blogger par excellence Ian Lind sent along this link to a photo of Waimea Canyon taken in 1953 on a family vacation with this comment: "I'm not sure where your mystery park is, but they stole the old railing from Waimea Canyon!" Take a look and decide for yourself--and while you're visiting Ian's site, be sure to explore his other "old kine pics" of Hawaii, his Ka'a'awa sunsets and sunrises, and if you are either a dog or cat person (or both), then his photos of "mornin' dogs" and his own family of felines will make you smile.

The great thing about this mystery park is the camping--and the pancakes. The two are of course related. There's no place to get "store-bought" pancakes in the park--you make your own over a little Coleman stove. I have to report that, more by luck than skill, I mixed up the the best pancakes of my life at our campsite in this mystery park. (These photos are not from the mystery park; they're of Yosemite Valley, from a 2005 hiking trip with my good buddy Jim Erler.) You know the secret to light pancakes, right? You separate the yolk from the whites of the eggs, and then beat the whites until they form soft peaks. Quickly fold the beaten whites into the batter at the last moment and voila, you get extra-light pancakes which rise ever so fluffily in the pan.  I didn't bother that morning--it was mid-May but still quite cold, and it had taken the sun

warming the tent to rouse me from the sleeping bag. The water jug had a crust of ice on top

but, hey, it's fun to be cold sometimes...get the water hot for coffee and then quickly

assemble the pre-measured ingredients for the pancake mix.

I didn't bother that morning--it was mid-May but still quite cold, and it had taken the sun

warming the tent to rouse me from the sleeping bag. The water jug had a crust of ice on top

but, hey, it's fun to be cold sometimes...get the water hot for coffee and then quickly

assemble the pre-measured ingredients for the pancake mix.

Perhaps it was the altitude, or the crisp morning air, I'm not sure, but those were the lightest, tenderest pancakes ever. Those of you who camp know that everything tastes better when you're camping--partly because it takes a lot of movement to get the camp set up, partly because the outdoors inspires a healthy hunger and partly because it forces you into a very basic form of cooking. Only a few other campers ventured into this park in May, so we had the campground to ourselves. That's ideal, of course, but even camping in busy Yosemite Valley in May has its rewards. While camp cooking tastes wonderful in Yosemite, too--there's a walk-in campground for tent campers on the east side of the valley, and so-called tent-cabins by the river--it's also great fun to put on your clean duds and saunter down to the Ahwahnee Hotel for their Sunday Brunch. The morning walk stimulates your appetite something fierce, and the brunch fortifies you for a good long hike up to Vernal Falls and Nevada Falls. Here's the Official Yosemite National Park website if you want to plan your next visit. If you'd like to solve the mystery park's location, check Chapter Six of my little novel I-State Lines for a big clue. Of course our two heroes are camping; the book is, after all, an exploration not just of the great American landscape but of that great American virtue, self-reliance. May 19, 2006 Where Is This?  Our Friday Quiz features a spectacular but relatively little-known park.

Our Friday Quiz features a spectacular but relatively little-known park.

Hint: this is not the Appalachians or the Sierra Nevada, nor is it the Grand Canyon (the canyon walls there are ocher, orange and rust-red). Be the first to identify the park or landscape behind me, and I'll send you a collector's copy of my book I-State Lines. So email me! Once you read the book, you'll find that a significant section of the two young heroes/anti-heroes' adventures occur in Iowa, the heartland of America. (Yes, each is both hero and anti-hero--it's the American way.) Though the heartland landscape of the country is not as dramatic as that pictured above, its scenery and identity provide many pleasures to observant visitors. The guys (the book's characters, Daz and Alex) set off for Liberty, Iowa, which is an actual town, though the people they meet there are entirely fictional. The name is of course meaningful in multiple ways; it reflects not just the two young protagonists' journey and the core of American identity, but the values rooted in the landscape: the liberties earned by growing one's own food and by actively participating in one's community, and the liberties lost once these values erode. My favorite bookstore to order books from is The Kaleidoscope: Our Focus Is You which happens to be in Iowa. Though physically sited at 112 1st Avenue NW, Hampton, IA 50441 (Tel: 641-456-2787, Fax: 641-456-2809) it is available to you via the miracle of the Internet. Shipping is free on all orders, and you can't beat that. I highly recommend their "for girls only" section. If you're looking for a gift for that bright, sensitive girl in your family or circle of friends, this is a wonderful place to start. May 18, 2006 After the Bubble: How Low Will We Go, Part II  My May 15 entry,

After the Bubble: How Low Will It Go? drew several thoughtful

and well-argued critiques. Interestingly, neither

correspondent disputed the housing bubble--they only contested the severity of the drop.

Fair enough; I think each makes valid refinements to my simple calculations.

But it's also possible that the drop will actually be worse than I projected.

My May 15 entry,

After the Bubble: How Low Will It Go? drew several thoughtful

and well-argued critiques. Interestingly, neither

correspondent disputed the housing bubble--they only contested the severity of the drop.

Fair enough; I think each makes valid refinements to my simple calculations.

But it's also possible that the drop will actually be worse than I projected.

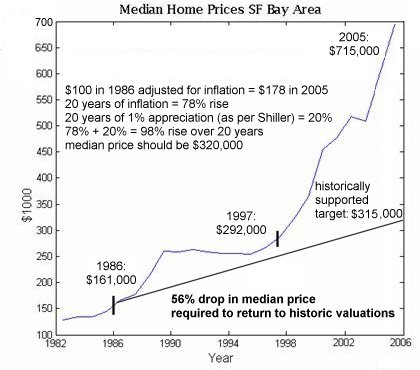

The first analyst, Robert C., notes that my straight line did not accurately reflect the fact that prices fluctuate above and below the trendline--an excellent point: "What I wish you to consider however is the 1% Shiller number and inflation. When you draw a straight line from 1986 you ignore both. Shiller does not and there is another issue. Inflation indicies since 1986 have been adjusted downward 3 times. Taken into account your straight line then curves up at a compound 1% on top of inflation at the old measure not the new one. OKAY, big deal. We are still on the same page but I see prices only 1.8x trendline while you are showing 2.3x overvaluations. Of course if you look again at your graph and adjust for my "corrections" you see c1970 and c1995 as periods of some undervaluation which in the fullness of time seems reasonable does it not? We come back together at the end because ultimately we need to dip below trend to return to trend. So, your return to norm is my bottom of the market." (emphasis added)Next up is a well-argued refinement of my calculations: "1. 20 years of 1% increment is not 20%. Its 1.01 times 1.01 20 times and minus 1. Thats roughly 22%.  Let's look at these assumptions more closely. While it's true that the last housing cycle

took six years to decline, it was not a bubble. Bubbles tend to fall as quickly as they rise.

The chart to the right illustrates the dot-com era Nasdaq. While this is a stock market,

the first chart reveals that the current real estate bubble inflated rapidly from 2003 through

mid-2005--a mere 2.5 years.

Let's look at these assumptions more closely. While it's true that the last housing cycle

took six years to decline, it was not a bubble. Bubbles tend to fall as quickly as they rise.

The chart to the right illustrates the dot-com era Nasdaq. While this is a stock market,

the first chart reveals that the current real estate bubble inflated rapidly from 2003 through

mid-2005--a mere 2.5 years.

Given the unprecedented level of excess in today's housing bubble, it is likely that the bubble will deflate as quickly as it rose. This would mean the majority of today's gains might evaporate in a little as 2 years. And as my first correspondent noted, markets fluctuate below the trendline after an extended period above the trendline--a behavior clearly visible in the chart of the Nasdaq bubble. In other words, the housing market is likely to fall well below the trendline in the initial post-bubble decline. Thus, while my second correspondent argues quite effectively for a "reversion to the trendline" number of $355,000, rather than my figure of $315,000, history suggests trendlines are broken to the downside as the bubble pops. This is a strong argument in favor of my original projection that housing prices will have to fall over 50% before reaching bottom. If prices fall fast, the effects of inflation will have little effect. If the median price of a S.F. Bay Area home falls from $715,000 to "only" $355,000 rather than to $315,000, will anyone's financial ruination be prevented? No. Next up: inflation. My second correspondent suggests that if the dollar falls in value, this will trigger inflation which will act to inflate property values. This sounds very reasonable, and here's why: But wait. If mortgage rates rise to 13%, who can afford to pay $700,000 for a house? That's the gotcha. No one can. That's the flaw in the idea that higher inflation will support housing prices. To keep inflation from accelerating out of control, Paul Volker and President Reagan raised interest rates to 15%, effectively ending all lending for autos and houses. The automakers, unable to sell cars with cheap loans, laid off hundreds of thousands of workers and lost billions. Home building dried up and blew away, as did real estate sales--who could qualify for a mortgage at 15%?--and of course, housing values sank, too. It was called "stagflation": stagnant economy, wages and employment coupled with high inflation. The "medicine" is high interest rates, which causes housing to drop back to what is affordable. Care to know what a $600,000 mortgage costs at 13% interest? Try $6,637 per month on a 30-year fixed mortgage. How many people can afford that? As I have noted here before: housing prices are correlated to the interest rate--period. If interest rates double from 5% to 10%, then housing will drop by 50% because people can only afford to pay so much for housing. You can finesse all kinds of numbers, but it all comes back to affordability. Once interest rates rise, housing necessarily plummets beause there are simply no buyers who can afford the inflated prices. I don't want to get too technical here, but there's also a fatal flaw in the idea that the dollar will drop through the floor. If euro banks are paying 4.5% and U.S. Treasuries are paying 9%, which one are you going to buy? The Treasuries, of course--and in so doing, you'll be buying dollars--which guess what, puts upward pressure on the value of the dollar. So as interest rates rise in the U.S. due to inflation, the dollar may well rise rather than fall. So we may well get deflating housing and appreciating currency at the same time.  Three other realities will send house prices plummeting to below-trendline levels: the

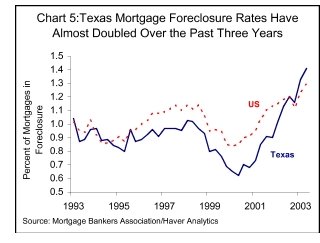

complete lack of buyers, oversupply of housing due to foreclosures and the loss of jobs.

As this chart reveals, virtually everyone who isn't poverty-stricken or in prison already

owns a house. As foreclosures rise (see

patrick.net for the latest news on foreclosure rates rising dramatically) then the current

oversupply of homes will climb to unprecedented heights--an ascent which will be accelerated by

massive job losses in the housing sector, which as CNN reports below, is fully 20%-25% of the

entire $12 trillion U.S. economy.

Housing slowdown to be widely felt:

Three other realities will send house prices plummeting to below-trendline levels: the

complete lack of buyers, oversupply of housing due to foreclosures and the loss of jobs.

As this chart reveals, virtually everyone who isn't poverty-stricken or in prison already

owns a house. As foreclosures rise (see

patrick.net for the latest news on foreclosure rates rising dramatically) then the current

oversupply of homes will climb to unprecedented heights--an ascent which will be accelerated by

massive job losses in the housing sector, which as CNN reports below, is fully 20%-25% of the

entire $12 trillion U.S. economy.

Housing slowdown to be widely felt:

"Housing accounts for between a fourth and a fifth of the GDP (gross domestic product)," said Walter Molony, spokesman for the National Association of Realtors, referring to the broad measure of the nation's economic activity. "So many other industries see sales tied to the purchase of a home. We get calls from Singer sewing machines about our home sales statistics."If the industry itself is predicting a direct job loss of 375,000--never mind the furniture salepeople, countertop manufacturers, and all the other millions of people indirectly employed by the housing industry--then you can bet the reality will be much worse. So take your pick: a decline in median house prices from $715,000 down to "only" $350,000 or a slightly more severe drop to $315,000. Will it really make any difference? Sadly, probably not. May 17, 2006 Why Post-Bubble Rents Matter  Why are post-bubble rents important? For one thing, they will, with enormous consequences,

set the official rate of inflation and thus future interest rates. As described here in

The

Housing - Inflation Connection, the cost of renting housing is fully 40% of the Consumer

Price Index (CPI). As rents dropped during the housing boom, they artificially suppressed

the CPI. If rents ever rise, they will quickly boost the CPI.

Why are post-bubble rents important? For one thing, they will, with enormous consequences,

set the official rate of inflation and thus future interest rates. As described here in

The

Housing - Inflation Connection, the cost of renting housing is fully 40% of the Consumer

Price Index (CPI). As rents dropped during the housing boom, they artificially suppressed

the CPI. If rents ever rise, they will quickly boost the CPI.

The big question is: will rents fall or rise as the housing bubble deflates? Given that part of what is causing the bubble to pop is overbuilding--the number of new condos and houses has outstripped demand--then common sense suggest rents will drop as desperate owners will lower rents to fill those hundreds of unsold units with tenants. That sounds reasonable--but then why does the Federal Reserve's Susan Bies think rents will actually rise? Rising rents may push CPI higher, Fed's Bies says. Noting that the CPI's gauge of housing costs is based on rents, Bies told a banking conference in answer to a question: "We've come through a period of weaker rents. Now, housing has really sort of peaked ... that may rejuvenate rents and so you may see may see that, in turn, higher (CPI) inflation going forward."You've probably read about "chain deflators" and all the arcane mechanisms by which the "official" rate of inflation is calculated, but any consumer can tell you inflation has been rising at a far faster clip than the official rate--however it's massaged. The "true" CPI has been artifically suppressed for the past 4 years because the housing boom dramatically lowered rents. In that sense, the Fed will be hoist on its own petard if the long-suppressed CPI breaks above the "true" rate. Why does this matter? Because bond traders expect the yield on a bond to exceed the rate of inflation. If inflation is tripping along at 5% annually, who would be dumb enough to buy a bond--which could drop precipitously in value should the dollar decline--which pays only 5%? You're nor making a dime on your investment, even as you're taking on a major risk of the dollar losing value. While the Fed governors have the luxury of playing around with chain deflators and the like, the bond market is the body which actually sets the long-term (mortgage) interest rates. If buyers of U.S. Treasury bonds start to get nervous about a rising CPI as evidence of rising inflation, they might demand a larger premium of risk--in other words, "show me the money or I'm not buying your bond." If bond rates rise to 8%, mortgage rates won't be far behind-- they will probably be ahead. And what do rising mortgage rates mean for the housing market? Declining prices, higher Adjustable Rate Mortgage (ARM) resets and thus more foreclosures as cash-strapped homeowners go broke. Ouch. But then maybe rents will fall as all these hundreds of thousands of units come on the market. Not so fast. There are countervailing forces which could, as Ms. Bies suggests, actually cause rents to rise. How is this possible? There are a number of factors: Boarded up or unfinished highrises were a common sight in Asian cities such as Bangkok after the Asian Contagion financial crises of the late 90s. If the builder or developer goes bankrupt, the lender is also not going to enter the rental housing business. The lender itself may well be pushed into bankruptcy should multiple developers and builders go bust. That would be the normal course of events in an over-building bubble such as this one. Which scenario is correct? Perhaps both. My photo of the two stately Victorian homes in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco provides a visual metaphor of how the rental market may develop. Rental units in desirable locations with good schools and close proximity to jobs and shopping districts will likely be rewarded with substantial increases in rent, even as thousands of houses and condos languish empty in overbuilt, distant or otherwise unattractive locations. The bland Victorian represents these perfectly good but utterly undesirable homes which may not attract renters at a price which enables the owner to cover his/her costs. Thus it may well turn out to be a bifurcated market in which a million foreclosed units sit vacant even as rents are rising in desirable locales which were not overbuilt. This would truly be the worst of all possible worlds, as rising rents would jack up the CPI even as lenders foreclosed on thousands of homes and then went bankrupt themselves as mortgage rates rose in lockstep with the CPI. Implausible? People who have witnessed the aftermath of overbuilding coupled with rising mortgage rates won't think so--they've seen rows of empty forlorn buildings and houses before. May 16, 2006 After the Bubble: Rents and Housing Values  Why do bubbles burst? One reason is that the supremely unprofitable nature of the

bubble asset becomes abundantly obvious. For instance, housing. Back in the overheated

real estate market of 1980-81, (Yes, Virginia, we had bubbles in the past, too) I recall an older real estate attorney shaking his head in dismay

as he told me, "It makes no sense to buy a house as an investment now, but people keep

buying them anyway." His point was that people were buying into a substantial monthly loss

which they presumed/hoped would be more than offset by appreciation.

Why do bubbles burst? One reason is that the supremely unprofitable nature of the

bubble asset becomes abundantly obvious. For instance, housing. Back in the overheated

real estate market of 1980-81, (Yes, Virginia, we had bubbles in the past, too) I recall an older real estate attorney shaking his head in dismay

as he told me, "It makes no sense to buy a house as an investment now, but people keep

buying them anyway." His point was that people were buying into a substantial monthly loss

which they presumed/hoped would be more than offset by appreciation.

My friend's point was simple: if an investment doesn't make money in the here and now, it's a lousy investment. As buying a second, third, fourth or fifth house or condo has become a popular investment alternative to a boring, low-yield bond or underperforming mutual fund, my friend's observation becomes highly relevant. It makes no business sense to count on appreciation if you're digging yourself a deeper financial hole every month. This is, of course, how bubbles form. With interest rates low, safe investments like certificates of deposit and bonds are unattractive; they're barely treading water above the rate of inflation or even losing ground. So the speculative, risky investments attract investors. As the money pours in (to gold, old cars, Chinese Internet stocks, copper futures, real estate, etc. etc.) then the asset prices rapidly inflate, attracting even more money to a "sure thing," "wave of the future," "real value," etc. etc. At some point, the punchbowl of cheap and easy credit is withdrawn, and the bubbly-drunk guests are stunned to find their high-flying jewel-encrusted carriage reduced to a mere pumpkin.  Can't sell that condo or house? "Just rent it out." Fine; but how does rental housing

stack up as a business in the real world? Let's take a look. First, a caveat. Any

scenario or extrapolation can be nitpicked or challenged in dozens of ways; quibbles abound

when someone has a vested interest in discrediting a line of reasoning or evidence.

Can't sell that condo or house? "Just rent it out." Fine; but how does rental housing

stack up as a business in the real world? Let's take a look. First, a caveat. Any

scenario or extrapolation can be nitpicked or challenged in dozens of ways; quibbles abound

when someone has a vested interest in discrediting a line of reasoning or evidence.

So don't take my word for it. If you're thinking of renting out your vacation or investment property, go talk to some landlords with five or ten years of experience. As this chart shows, the historic ratio between housing and rents--that is, the snapshot of housing as an actual business rather than a speculative gamble--has reached hitherto unknown heights. "Just rent it out." Easier said than done. For starters: no uninsured worker ever fell off the roof of a municipal bond. No CD was ever trashed by vengeful tenants, and the plumbing bill for a savings account never rocked you back on your heels. Then there's the uncomfortable fact that rents have declined in many locales since the 2000 heyday, or have been flat for years: Bay Area rents stay the same. As the first chart shows, rents nationally have barely kept ahead of inflation. In other words: even as housing has shot up, rents have remained flat or even declined. Anyone expecting to make money on rising rents may be sorely disappointed. According to Barron's, Rental income nationally has fallen to $147.8 billion from the peak of $186.6 billion back in April 2002. OK, let's crunch some numbers. Let's take a property purchased for $500,000 that rents for $2,000 a month. Is this a good business? Maybe a $500,000 house rents for more than $2,000 in your city, but in my region, since $500,000 only gets you a rundown bungalow in a lousy neighborhood or a small condo, you'd be lucky to get even close to $2,000 rent for your $500K investment. First off, unless you "fudged" (i.e. lied) on your loan application, claiming that the property was your principal residence, an investment property carries higher loan rates and requires a 20-25% down payment. So let's assume you put down $100,000 and incurred another $5,000 in loan and closing costs, meaning that your investment in the property has to yield at least what the $105,000 cash would earn in a muni or high-grade corporate bond--at least 6% (but 7% is certainly available) or $6,300 a year. Next is your loan balance of $400,000. Let's say you have an interest rate of $6.5%--very good for an investment property.The payments of principal and interest, according to the calculator at MSN Money, would total $2,528 per month. For maintenance, let's assume your condo fees are about $400, or general upkeep on the house (maintaining the yard and typical repairs) will run an equivalent amount. (Remember that every once in a while there will be large bills for items such as replacing old sewer lines, a new furnace, a new roof, tree trimming, a new countertop or bathroom floor, etc., unless it's a brand-new house.) Then there's management fees, which run about 6% of rent (even if you handle this yourself, your time isn't free), so that's 6% of $24,000 annual rent or $1,400 ($120 a month). Insurance varies widely around the country but let's plug in $100 a month ($1,200 annually). Property taxes also vary widely, but let's assume 1% annually is fair (though it's much higher in many locales such as New York, Texas and California). That's $5,000 a year or about $400 a month. Since it's unwise to assume the property will never be vacant, let's shave 10% off the annual rent as an allowance for vacancies, reducing the $2,000 per month to $1,800. (Note that realtors are pleased to wave huge summer rental numbers around during the sales pitch but the reality is that many vacation homes sit empty unless someone spends major money advertising and promoting the property.) As expenses add up to about $3,500 per month, that leaves a net loss of $1,700 per month, or $20,400 annually. But wait, you say--what about depreciation? Fine. The first thing to note about depreciation is that it comes back to haunt you when you sell the property, as all your depreciation is "recovered" when it comes time to pay the tax on your gain (if any). And remember, as an investment, there's no $500,000 giveaway on the gain; you pay tax on dollar one of that gain and recovered depreciation. Also note that you can only depreciate the building, not the land, so you can't depreciate the full $500K value. Taking a standard 40-year depreciation (let's say the building is $350,000 of the $500K price, yielding an annual depreciation of $8,750), your loss is knocked down all the way to $11,650: about a $1,000 out of pocket a month, even counting depreciation. And let's not forget that you're foregoing $6,300 in net income by leaving the $105,000 cash in a losing investment. You can quibble--but I got a loan at 5%, rents are going up in my area, I'll maintain the place myself, etc. etc.--but the bottom line is unavoidable: this is a lousy business proposition unless you can collect at least $3,500 rent per month for the property. Then there's the risks I mentioned. If you try to save money by hiring unlicensed, uninsured workers, and one gets injured, you could be facing a lawsuit which your homeowner's insurance may be unwilling to settle. There are no guarantees in the rental housing business. You may not be able to find a decent tenant no matter how much you advertise, or you may get a tenant who suffers some family trouble or medical emergency and as a result can't pay the rent. The rental housing business is not risk-free. Neither are bonds, of course, but a short-term CD isn't going to get a stopped up toilet or suddenly stop paying the rent. "Just rent it out." Sure, but be aware it isn't that easy and it almost certainly isn't profitable--unless you bought ten years ago in a desirable neighborhood and have spent serious money keeping the property in tip-top shape. May 15, 2006 After the Bubble: How Low Will It Go?  How low will housing go as the bubble bursts? For an answer, let's turn to

Irrational Exuberance

How low will housing go as the bubble bursts? For an answer, let's turn to

Irrational Exuberance