Writing/Film

Dear Aspiring Writers: The Worst Advice You'll

Ever Read

A Literary Look at

I-State Lines

Spirited Away: Decay and Renewal

An American Poem

(Robinson Jeffers)

Taoist Chinese Poems

The Nelson Touch

"It's all about oil, isn't it?"

Kurosawa's High and Low

A Bountiful Mutiny

Howl's Moving Castle

Thailand's Iron Ladies

Trois Colours: Red

The Thin Man: Thoroughly Modern Movies

Why My Book Is Better Than the DaVinci Code

Iranian Films: The Mirror

Piratical Nonsense

A Real Pirate Movie: Captain Blood

9 more in archive

Recommended Books

American Identity

Hapas: The New America

Can You Tell What I am? Part I

Can You Tell What I am? Part II

Only in America

Self-Reliance

Your Tattoo in 50 Years

The American House and Frank Lloyd Wright

Cultural Commentaries

On Hatred and Anti-Americanism

Anti-Americanism

Part 2

Anti-Americanism

Part 3

French-Bashing

Germany: We All Have Problems, But...

Kroika! Chronicles

This Blog Sells Out

Doom and Gloom Sells

The Kroika Mascot-"Auspicious Pet"

Wal-Mart and Kroika

Kroika and Starsbuck Take a Hit

Kroika Ad 1

Kroika Ad 2

Kroika Ad 3

Kroika Ad 4

Kroika Makes Bid for Oreo (April 1)

Unfolding Crises: Asia

China: An Interim Report

Shanghai Postcard 2004

Corruption and Avian Flu: China's Dynamic Duo

Exporting the Real Estate Bubble to China

Is the Bloom Off the China Rose?

China Irony: Steel, Marx & Capital

Curing The U.S. and China's Dysfunctional Relationship

China and U.S. Inflation

Trade with China: Making Out Like a Bandit

Whither China?

Will the Housing Bust Take Down China?

China's Dependence on Exports to U.S.; Is China About to Pop?

8 more

Battle for the Soul

of America

Katrina, Vietnam, Iraq: National Purpose, National Sacrifice

Is This a Nation at War?

A Nation in Denial

Why Is This Such a Tepid Time?

That Price Isn't Cheap, It's Subsidized

The Most Hated Company in America

U.S. Fascists Seek Ban on Cancer Vaccine

The Truth About Christmas

American Dream or American Nightmare?

2006 Sea Change

Obesity and Debt

Immigration Ironies

U.S. Healthcare: Working Toward a Real Solution

A Drug Industry Running Amok

Where There Is Ruin

10 more

Financial Meltdown Watch

What This Country Needs Is a... Good Recession

Are We Entering the Next Age of Turmoil?

Why Inflation Appears Low

Doubling Down on 5-Card No-See-Um

A Rickety Global House of Cards

Are Japan and Germany Truly on the Mend?

Unprecedented Risk 2

Could One Rogue Trader Bring Down the Market?

Worried about Inflation? Stop Measuring It

Economy Great? Bah, Humbug

Huge Deficits and Huge Profits: Coincidence?

Who's The Largest Exporter?

Three Snapshots of the U.S. Economy

Loaded for Bear

Comparing Nasdaq to Depression-Era Dow

Who's Buying Treasury Bonds? And Why?

Derivatives: Wall Street Fiddles, Rome Smolders

Financial Chickens Coming Home to Roost

Is the Stock Market on the Same Planet as the Economy?

The Housing-Recession-Oil-Healthcare Connection

Could We Have Deflation and Inflation At the Same Time?

What We Know, What We Can Safely Predict

Bankruptcy U.S.A.: Medicare, Greed and Collapse

Sucker's Rally

A Whiff of Apocalypse

Where There Is Ruin II: Social Security

31 more

Planetary Meltdown Watch

The Immensity of Global Warming

Sun Sets on Skeptics of Global Warming

Housing Bubble Watch

Charting Unaffordability

A Monster of a Housing Bubble

A Coup de Grace to the Economy

Hidden Costs of the Housing Bubble

Housing Bubble? What Bubble?

Housing Bubble II

Housing Bubble III: Pop!

Housing Market Slips Toward Cliff

Housing Market Demographics

Housing: Catching the Falling Knife

Five Stages of the Housing Bubble

Derailing the Property Tax Gravy Train

Bubbling Property Taxes

Have You Checked Your Property Taxes Recently?

Housing Bubble: Where's the Bottom?

Housing Bubble: Bottom II

The Housing - Inflation Connection

The Coming Foreclosure Nightmare 1

How Many Foreclosures Will Hit the Market?

Housing Wealth Effect Shifts Into Reverse

Housing Bubble Bust Will Take Down the Global Economy

The New Road to Serfdom: A Negative-Equity Mortgage

The Housing-Savings-Recession Connection

After the Bubble: How Low Will It Go?

After the Bubble: Rents and Housing Values

Why Post-Bubble Rents Matter

After the Bubble: How Low Will We Go, Part II

Housing: 10% Decline May Trigger Financial Ruin

How to Buy a $450K Home for $750K

Inflation and Housing: Calculating the Bust

The Growing Financial Risks of the Housing Bubble

Construction Defects: The Flood to Come?

Construction Defects

Part II

Who Gets Hammered in the 2007 Housing Bust

Real Estate Bust: The Exhaustion of Debt

What Happens When Housing Employment Plummets?

One More Hole in the Housing Bubble: Insurance

Financial Kryptonite in a "Super-Strength" Housing Market

Three Secrets to Unloading Property Today

Welcome to Fantasyland: Housing's "Soft Landing"

Why Is the Median House Price Still Rising?

Why Median Prices Appear to be Rising?

The Root Cause of the Housing Bubble

Housing Dominoes Fall

Twilight for Exurbia?

Phase Transitions, Symmetry and Post-Bubble Declines

10 more

Oil/Energy Crises

Whither Oil?

How much Is a Gallon of Gas Worth?

The End of Cheap Oil

Natural Gas, Naturally High

Arab Oil Money and U.S. Treasuries: Quid Pro Quo?

The C.I.A., Oil and the Wisdom of Crowds

The Flutter of a Butterfly's Wings?

A One-Two Punch to a Glass Jaw

Running Out Of Oil vs. Running Out of Cheap Oil

2 more

Outside the Box

How to Make a Favicon

Asian Emoticons

In Memoriam: Winky Cosmos

The Wheeled Vagabonds

Geezer Rock Overload

Paying for Web Content

In a Humorous Vein

If Only Writers Had Uniforms

Opening the Kimono

Happiness for Sale: Jank Coffee

Ten Guaranteed Predictions for 2010

Why My Book Is Better Than the DaVinci Code

My Brand Management Stinks

Design Follies

The New Jank Coffee Shop

Jank Coffee, Upscale Tropic Style

One-Word Titles

Complacency

Nostalgia

Lifespans

Praxis

Keys to Affordable Housing

U.S. Conservation & China

Steve Toma, Me & Skil 77s: 30 years of Labor

Real Science in the Bolivian Forest

Deforestation and Sustainable Forestry

The Solar Economy (book)

The Problem with Techno-Fixes

I Love Technology, I Hate Technology

How To Blow off Web Ads and More

2 more

Health, Wealth & Demographics

Beauty of the Augmented (Korean) Kind

Demographics and War

The Healthiest Cold Cereal: Surprise!

900 Miles to the Gallon

Are Our Cities Making Us Fat?

One Serving of Deception

Is Obesity an Inflammatory Response?

Demographics & National Bankruptcy

The Decline of Europe: A Demographic Done Deal?

Are the Risks of Obesity Overstated?

Healthcare: Unaffordable Everywhere

Medication Nation

The New Disease We Just Know You've Got

Can You Can Tell Which Pill Is Fake?

Bankruptcy U.S.A.: Medicare, Greed and Collapse

The 10 Secrets to Permanent Weight Loss

5 more

Landscapes

Selling the Landscape

The Downside of Density

Building Heights and Arboral Roots

Terroir: France & California

L.A.: It's About Cheap Oil

The Last Redwood

Airport Walkabouts

Waimea Canyon, Yosemite, Camping & Pancakes

Nourishment

The French Village Bakery

Ideas

What Is Happiness?

Our Education System: a Factory Metaphor?

Understanding Globalization: Braudel

Can You Create Creativity?

Do Average People Know More Than Their Leaders?

On The Impermanence of Work

Flattening the Knowledge Curve: The "Googling" Effect

Human Bandwidth and Knowledge

Iraqi Guangxi

Splogs, Blogs and "News"

"There is no alternative to being yourself"

Is There a Cycle to War?

Leisure, Time and Valentines

Is the Web a Giant Copy Machine?

Science Matters

Anti-Missile Defense: Boost Phase Vulnerability

History

The Strolling Bones: Rock of Ages

Bad Karma: Election Fraud 1960

Hiroshima: First Use

All the Tea in China, All the Ginseng in America

Friday Quiz

Pet Obesity

The Origins of Carbonara

Organic Farms

Oil and Renewable Energy

Human Diseases

Wine and Alzheimers

Biggest Consumers of Chocolate

7 more

Essential Books

The Misbehavior of Markets

Boiling Point (Global Warming)

Our Stolen Future: How We Are Threatening Our Fertility, Intelligence and Survival

How We Know What Isn't So

Fewer: How the New Demography of Depopulation Will Shape Our Future

The Coming Generational Storm: What You Need to Know about America's Economic Future

The Third Chimpanzee: The Evolution and Future of the Human Animal

The Future of Life

Beyond Oil: The View from Hubbert's Peak

The Party's Over: Oil, War and the Fate of Industrial Societies

The Solar Economy: Renewable Energy for a Sustainable Global Future

The Dollar Crisis: Causes, Consequences, Cures

Running On Empty: How The Democratic and Republican Parties Are Bankrupting Our Future and What Americans Can Do About It

Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy Revised and Updated . .

Recommended Books

More book reviews

Archives:

weblog July 2006

weblog June 2006

weblog May 2006

weblog April 2006

weblog March 2006

weblog February 2006

weblog January 2006

weblog December 2005

weblog November 2005

weblog October 2005

weblog September 2005

weblog August 2005

weblog July 2005

weblog June 2005

weblog May 2005

What's New, 2/03 - 5/05

|

|

August 31, 2006

The Colossus, Globalization, and More: Wal-Mart

My recent entry on Wal-Mart (scroll down to August 29) drew two excellent commentaries,

which are reprinted below. But before we get to those, let's cover the context

surrounding any discussion of Wal-Mart. (Note: this is a long entry, but well worth

reading through to the end.)

1. Size matters. Wal-Mart is by far the world's largest retailer. Though this

chart is a bit dated (2005 sales at Wal-Mart exceeded $285 billion, and 2006 sales are on

track to hit over $300 billion), the relative weight of Wal-Mart compared to its global

competitors hasn't changed. It is the proverbial 800-pound gorilla. Its policies can

literally move the world.

1. Size matters. Wal-Mart is by far the world's largest retailer. Though this

chart is a bit dated (2005 sales at Wal-Mart exceeded $285 billion, and 2006 sales are on

track to hit over $300 billion), the relative weight of Wal-Mart compared to its global

competitors hasn't changed. It is the proverbial 800-pound gorilla. Its policies can

literally move the world.

2. Wal-Mart very ably tells its side of many issues on this website,

Wal-Martfacts.com which I recommend checking out.

3. For a variety of reasons, Wal-Mart excites emotional responses in many of us.

I believe the reader-commentators I quote at length below make valid points and ask valid

questions which are not emotionally biased; while I do not have answers for all the issues

raised, I would like to clarify my own position. (Feel free to scroll down and read the

corresponents comments first and then return to my own comments.)

4. I don't "hate" Wal-Mart but I do see evidence that they rely on taxpayer funding as

part of their low-cost business plan--something which not all their competitors do.

Hence, they

are gaming the system to the disadvantage of taxpayers. That is my core objection. If one

retailer gets to off-load healthcare coverage onto the government/taxpayers, then

all retailers should be

offered that same advantage via a "level playing field."

If one retailer pays a decent wage and provides its employees with some medical insurance

and 401K-type pension, while another pays lower wages and few benefits, because it knows

the government will provide those for its employees if it doesn't, then who wins in the

long run? The competitor (Wal-Mart) who is basically using the government to pay some of its

employee benefits (medical and retirement).

If one retailer pays a decent wage and provides its employees with some medical insurance

and 401K-type pension, while another pays lower wages and few benefits, because it knows

the government will provide those for its employees if it doesn't, then who wins in the

long run? The competitor (Wal-Mart) who is basically using the government to pay some of its

employee benefits (medical and retirement).

Wouldn't it be fairer to require a level playing field for all retailers? In Hawaii, for instance,

a law requires employers to pay 50% of all employees' medical insurance, regardless of the

firm's size. (I think the cut-off is 20 hours per week, which of course can be evaded by hiring people to work

18 hours a week). The idea is, all employees get some help in medical coverage, and all

employers pay some of those expenses. Hence: a level playing field.

5. The alternative is what Japan and Europe offer employers and citizens: the government provides the medical

coverage, freeing all employers equally from that burden. What strikes me as patently

unfair and thus uncompetitive about Wal-Mart et. al. is that the government picks up the

tab for thousands of their employees while other global corporations such as Ford, Boeing,

Costco, Hewlett-Packard, etc.

cover all or a significant portion of these costs.

6. As for China and other low-wage havens, let's look at what U.S. retailers can do, even in

a global workforce situation. If U.S. corporations require overseas contract employees to be paid, say,

$120 rather than $80 a month, and that their work hours be limited to 10 hours per day, etc.,

then some factory will switch over to meet those standards in order to serve the U.S.

market--or Wal-Mart alone, since it is basically a small nation in and of itself.

Their competitors will eventually

find it hard to recruit the best workers, as they have migrated to the better

wages and working conditions of the factory meeting U.S. standards.

Since factory wages are such a small part of the final product's retail cost, U.S.

retailers such as Wal-Mart can improve the global working conditions and wages for many

workers without unduly jeopardizing their global competitive position. Companies such

as Hewlett-Packard have made an effort to require minimal standards for the workplaces

of their contract manufacturers (OEMs) in China (including inspections to oversee compliance);

if H-P can do it, then why can't Wal-Mart?

7. The argument that requiring Wal-Mart to pay modest benefits and decent wages would

significantly impact its low-income customers is false. A 20% increase in wages and benefits

would not translate into a 20% rise in the retail cost of goods. Although I cannot locate

any statistics to use as metrics, I suspect the entire

year's impact of slightly higher prices would be equivalent to about the cost of

one meal for the family at McDonalds and an armfull of DVD rentals. Yet the impact on the

employee would be very significant.

To summarize one argument offered in favor of the Wal-Mart model: their low prices outweigh

the low wages if you

consider the benefits to the entire community. But this is a false analysis. The question should be: how

does Wal-Mart compare against a competitor such as Costco which pays decent wages and benefits

while also offering low prices? Are Costco prices low enough to save consumers money?

Yes. Do they pay employees more than Wal-Mart? Yes. Do they still make a profit? Yes.

(While I know Costco pays well anecdotally, I was unable to find statistics to back this up--

if anyone has comparative stats on wages and benefits paid by Target, Costco and Wal-Mart,

I would appreciate a link.)

8. This discussion also raises another theme with which readers of this blog are familar--the looming

crises in American healthcare (or lack of it). According to The Wall Street Journal,

the number of people without health insurance increased to 46.6 million in 2005.

(About 45.3 million people were without insurance the year before. Hey, a million here and

a million there, and pretty soon you're talking about a lot of people.)

Then there's the millions of people like myself, self-employed or small business owners,

who are hanging onto their insurance coverage by a thin thread.

Many people (myself included) believe that the U.S. will get a national healthcare plan

only when Corporate America finds their medical costs so heavy that

there is simply no other way to stay in business but to off-load healthcare onto

the Federal government. At that magical tipping point, all the objections and all the

rah-rah about free enterprise will suddenly vanish, because profits (or in the case of

the U.S. auto industry, their very survival) will be at stake.

In summary: Global corporations can afford to pay their employees wages and benefits

such that said employees don't need public assistance to live. If we as a nation want

retailers to offer some form of work-welfare, then all retailers should share the same

government benefits/support structure.

OK, on to the readers' commentaries. Here is one who points out that small business games the system by paying wages

under the table, avoiding both taxes and benefits costs:

My first "real" job back in 1979 was inside a grocery store (I was the clean up boy in the butcher shop working for $2 an hour cash + free cokes and candy). When I graduated from High School in 1983 I had moved on from clean up boy to carry out boy to cashier and weekend manager of the little Burlingame store. The Italian Immigrants that owned the place never put me on payroll, paid any taxes or gave me any health care but they more than doubled my salary to $5 an hour cash + let me have a case of beer every now and then...

I had to laugh when I read: (from a previous entry on Wal-Mart, link at the end of 8/29 entry)

"The low wages and benefits paid by Wal-Mart insures that a significant percentage of their workers' medical costs are paid by taxpayers via Medicaid. Yes, Medicaid--the medical benefits reserved for the poor of our nation. Those $7-8/hour jobs place the workers solidly in the extreme poor of our nation, those earning $15,000 or less annually. (This is more than most writers earn by scribbling, but that just shows lousy pay isn't enough to deter fools.)"

I know it is popular to hate Wal Mart, but what is the difference between Wal Mart paying $8 an hour without any health care and some hip Berkeley coffee shop paying $8 an hour without any health care. The difference is that while Wal Mart may not pay high wages, and they may not pay heath care, but at least they hire legal Americans and pay taxes (I know that a company Wal Mart hired to clean stores did get caught with illegal aliens). Almost everyone I know in the restaurant, retail and real estate business hires more illegal aliens, pays less total cash compensation and pays less taxes to the government than Wal Mart...

I do a lot of retail lending and addition to your blog I read

www.morningnewsbeat.com

(which has a "Wal Mart Watch" section)

on a regular basis. Sure Wal Mart and Super Wal Mart are making it hard on other retailers,

but Safeway and Luckys forced the closure of almost all the little stores in SF where my

parents shopped as kids and most of the little grocery stores on the Peninsula

(including the one I worked at).

It is not popular to say this but the small business that are much loved by the liberal

left are a "double whammy" to the economy. Not only do most small and family business

hire as many illegal aliens as possible (and pay rock bottom wages) or pay US citizens

cash but they avoid lots of income taxes by rarely declaring much (or any) of their

cash income.

As a commercial real estate lender I see the tax returns of all our small business owning

Borrowers and many of these guys worth millions "make" (according to their tax returns)

about as much as a Wal Mart employee or a struggling writer. As much as people hate Wal

Mart at least they withhold taxes from paychecks and have audited financial statements

and pay taxes on their income.

Next up is correspondent Michael Goodfellow, who last contributed an incisive analysis of

the looming Social Security crisis. He observes that the key drivers to many of these issues

are larger than Wal-Mart: technology and education:

Wal-Mart seems to have become a symbol of globalization (especially goods from China) and

low-paying jobs in the U.S.. Wal-Mart stores have drawn a lot of local opposition from

activists, despite their popularity with shoppers. States like Maryland are trying to

force them to provide health insurance. I would really like critics to give honest

answers to the following questions:

1. Why is there a huge line of applicants for those crappy Wal-Mart jobs whenever they open up a new store? Do none of those people know how horrible it all is?

2. The "taxpayer subsidy" critics mention is of course government programs like food stamps and Medicaid, which large families with low income qualify for. Wal-Mart is hardly unique in this since they pay well over minimum wage.

So the current situation is that all taxpayers fork over a bit of money to low-paid workers. If Wal-Mart raised its compensation they would also raise their prices to pay for it. So then you'd have Wal-Mart customers paying extra to subsidize low-income workers. But since Wal-Mart customers are disproportionately low-income themselves, the price increase would hit the portion of the population least able to afford it.

What's more, if Wal-Mart is required to offer health insurance, they would rationally discriminate against elderly employees, part-timers or ones with families. Is this really what you want?

3. If Wal-Mart didn't exist, would China raise all its prices and pay all its workers more? Or would they just sell to other retail outlets? If they did get more for their goods, would any of that reach workers there?

4. Third-world workers in general are not slaves. Press gangs do not drag them off the streets to make Nikes. If they have taken a job in a sweatshop, it's because that's the best job they could find. If you close that factory, won't they just go to the next, crappier job that they had previously turned down?

5. If you make third world countries obey U.S. environmental standards and working standards and pay standards, what advantage would they have left? It's not like they have a better educated workforce or anything else to offer. Cheap labor is their only way into the world market. It's their first step up the ladder to first-world status. This has worked for Japan, South Korea and now China. Why would you want to stop it?

6. In more socialist countries, Wal-Mart might not exist. Instead we'd have a core of long-term unemployed people like in Europe, plus expensive retail with poor service. Is that better?

The point of these questions is that by slapping down Wal-Mart and what it stands for, you might not be helping anyone, least of all the low-wage employees you are so worried about.

It's also worth wondering why Wal-Mart exists in the first place? The criticism of Wal-Mart makes it sound like a symptom of moral decline. Weak unions, Big Business exploiting workers with crappy wages, slave-labor economies in China, etc. It's far more likely to be due to changes in technology.

For example, consider overseas call centers. You might explain these as simple greed -- corporations reducing their costs by sending jobs overseas. But companies have always wanted to reduce their costs. Why didn't they send those jobs overseas 30 years ago? The answer is technology. Back in the 70's, overseas calls were something like $1 a minute. If an Indian worker was paid 50 cents an hour and an American $6, it didn't matter, since the phone call was $60 an hour. Now the cost of phone calls has dropped to a couple of cents a minute (a dollar an hour) and suddenly an overseas call center makes a lot of sense.

I've read similar things about containerized cargo. Before that was introduced in the 60's and 70's, cargo was unloaded and repackaged multiple times in transit. With containers, it all moves more cheaply, more quickly and more reliably. This in turn enabled all the just-in-time worldwide supply chains that make a company like Wal-Mart (and many other companies) possible.

Cheap computers and networks are also a factor. I've read that Wal-Mart is as much an information technology story as it is a retail story. After all, according to their annual report, they have 1.6 million employees, 68,000 suppliers, and thousands of stores. Getting everything where it should be in a network this size just wasn't possible back before computerization.

We want cheap phone calls, cheap computers and cheap shipping. The side effect is global supply chains and the creation of large companies like Wal-Mart and all the other big-box stores that are killing small retailers. When retailing becomes a technology and supply chain story, the "mom and pop" stores just can't compete.

Finally, wages would be higher if there weren't a worldwide oversupply of unskilled labor. This is especially ridiculous in the U.S. considering how much we spend on primary education. A high-school graduate here has received anywhere from $70,000 to $150,000 in education. It's a crime that for so many people, this expensive education gets you the skills to tote boxes around at Wal-Mart, or compete with nearly illiterate factory workers in third world countries. We should be moving up the chain and producing more valuable goods. Wal-Mart should be forced to pay more wages, not because government passes a law, but because there are so few people who want those jobs.

I don't see this situation getting any better. As technology improves, more and more low-skilled work will be automated. We've let education stagnate for years, with only trivial increases in test scores. The tests themselves measure little that has any value in getting a job. Large numbers of low-income people willing to work for Wal-Mart wages is the price of that neglect. It's not a story about greed.

Thank you, Michael and our other reader, for such cogent commentaries. Thanks to you,

I have a better understanding of the issues raised by critiques of Wal-Mart.

August 30, 2006

You Can't Have It Both Ways

A great conundrum now faces the Federal Reserve. Should they continue to raise

interest rates to quell inflation and support the dollar, or should they begin

to drop rates to counter the slowing U.S. economy? There are good reasons to want both--

a low-inflation, strong-dollar economy and an easy-money economy where virtually anyone

with a job can borrow lots of money cheaply.

Ah, but you can't have it both ways. Either way the Fed goes, they will get

the same result--recession. Wait a minute--how is that possible? Read on.

Ah, but you can't have it both ways. Either way the Fed goes, they will get

the same result--recession. Wait a minute--how is that possible? Read on.

Just for laughs, let's say the Fed is under tremendous political pressure to keep this

debt-based, housing-based, asset-bubble-based "prosperity" running at least through 2008.

(As to why this might be so, I'll let you fill in the blanks: to stay in power you must

win elections. To win elections, you must fatten the wallets of voters and provide them

with a happy story about the golden future just ahead.)

The Fed has only one hope to accomplish this--begin dropping rates from 6% back down to

3% or less. We all know a quarter point here and there is meaningless; to re-inflate the

housing bubble and re-ignite consumer borrowing, the Fed has to pump heavy steroids into

the economy--massive liquidity, easy borrowing standards, and low rates.

But hey, don't they already provide the first two? Yes, they do. And if that's not working,

then the only stimulant left is much lower rates. But will there be any consequences to

lowering rates? Maybe this time there will be. Our exporting trading partners,

Japan, Europe, China and the OPEC oil producers, have willingly (or unwillingly, who knows)

entered into a devil's pact with us akin to the pusher and the drug addict. They buy our

bonds (that is, our IOUs or debt) to keep the dollar afloat and their currencies weak,

and in exchange we buy about $1 trillion more of their exports than we can afford (the

trade deficit). They sell all this stuff to us to support their economies, and to enable

all that borrowing, they pump their profits back into the dollar and bonds.

We're both addicts, actually, and both pushers: they need our market to keep going, and

we need their cash/savings to keep our debt/borrowing/spending raft afloat. But observers such as Warren Buffett have

long feared that this imbalance will come to a bad end, and that the dollar will at some

point suffer a serious devaluation.

What could trigger such a devaluation? An abandonment of the dollar by foreign investors

who suddenly realize even their massive buying can no longer keep the dollar high. Or

perhaps Venezuela, Iran and Russia announce that they're pricing their oil in euros. The

final straw is unknown, but the risks, at least to people like Buffett, appear to be growing.

(Correspondent Wayne D. has posted Buffett's comments on

his board,

Warren Buffett on the dollar.)

What could trigger such a devaluation? An abandonment of the dollar by foreign investors

who suddenly realize even their massive buying can no longer keep the dollar high. Or

perhaps Venezuela, Iran and Russia announce that they're pricing their oil in euros. The

final straw is unknown, but the risks, at least to people like Buffett, appear to be growing.

(Correspondent Wayne D. has posted Buffett's comments on

his board,

Warren Buffett on the dollar.)

For more of Buffett's views, go to the Berkshire Hathaway annual report and scroll to

pages 18-25

But as I argued in a November 10, 2003 article in Fortune, (available at berkshirehathaway.com),

our country’s trade practices are weighing down the dollar. The decline in its value has already been

substantial, but is nevertheless likely to continue. Without policy changes, currency markets could even

become disorderly and generate spillover effects, both political and financial. No one knows whether these

problems will materialize. But such a scenario is a far-from-remote possibility that policymakers should be

considering now. Their bent, however, is to lean toward not-so-benign neglect: A 318-page Congressional

study of the consequences of unremitting trade deficits was published in November 2000 and has been

gathering dust ever since. The study was ordered after the deficit hit a then-alarming $263 billion in 1999;

by last year it had risen to $618 billion. (note: it has since risen to over $800 billion.)

Some observers believe the dollar is fundamentally more valuable than competing currencies

(for instance, Mish), but there are technical analysis reasons to suspect the dollar could

drop from 83 on the DX index (click here to see the chart) all the way down to 52--a 37% devaluation.

Were this to occur, what would happen? To start with, imports from everywhere but China

would rise by that 37%, and our exports would get a 37% discount. There are all sorts

of consequences of such a massive currency adjustment, consequences which interact in

unpredictable ways.

For instance, since we import so much, then a big jump in import prices would feed inflation:

we're paying more for the same goods. Except from China, of course, which pegs the yuan

at 8 to the dollar. A dollar devaluation would be a boon to China, as it would discount

their goods in Europe and Asia while leaving exports to the U.S. untouched. In that sense,

a dollar devaluation would be favorable to China, and not something they would fear. Perhaps

they would even welcome it as a support to their exports and a "tax" on imports from Japan

and Europe.

For instance, since we import so much, then a big jump in import prices would feed inflation:

we're paying more for the same goods. Except from China, of course, which pegs the yuan

at 8 to the dollar. A dollar devaluation would be a boon to China, as it would discount

their goods in Europe and Asia while leaving exports to the U.S. untouched. In that sense,

a dollar devaluation would be favorable to China, and not something they would fear. Perhaps

they would even welcome it as a support to their exports and a "tax" on imports from Japan

and Europe.

Meanwhile, the oil exporters would suffer a 37% haircut--a haircut they are unlikely to

enjoy. Since oil is priced in dollars, they would get 37% less for their oil--unless, of

course, they spent that money in the U.S. Then their purchasing power would remain the same.

One could easily make the case that the U.S. would welcome such a move, as it would bolster

our sales to the oil-exporting nations. Japan and Europe would welcome such a devaluation as

well, as it would immediately drop the cost of oil in their currencies by 37%--a very hefty

discount. Again, the devaluation would be neutral to China, as long as its currency

remained pegged to the dollar.

But in another way, Japan and Europe would

certainly not welcome such a devaluation, as it would impose an instant 37% "tax" on their

exports to the U.S. Which is more important--cheaper oil or exports to the U.S.? That

is yet another sticky wicket.

But in another way, Japan and Europe would

certainly not welcome such a devaluation, as it would impose an instant 37% "tax" on their

exports to the U.S. Which is more important--cheaper oil or exports to the U.S.? That

is yet another sticky wicket.

If, however, the oil exporters are unhappy with their haircut, they could decide to price

oil in a basket of currencies rather than the dollar--a move which would instantly raise

the cost of oil to the U.S. That move alone could trigger a recession in the U.S., even

if the 37% increase in the cost of imported goods failed to do so.

The consequences of a dollar devaluation are uncertain, as they are negative for some

global players and positive for others. Such a dislocation carries high risks for the U.S.

and the global economy.

One way to avoid this mess would be to support the dollar with higher interest rates.

But if the Fed raises rates, it will likely tip the U.S. economy into recession. Ah,

but you can't have it both ways.

August 29, 2006

Another Perspective on Wal-Mart

I am continually astonished (and of course gratified) by the high bandwidth, knowledge

and experience of this humble site's readers. You, the readers, provide information

to your fellow readers which is often unavailable elsewhere.

I am continually astonished (and of course gratified) by the high bandwidth, knowledge

and experience of this humble site's readers. You, the readers, provide information

to your fellow readers which is often unavailable elsewhere.

In that spirit, I offer you one executive reader's experience with that colossus of global

retailing, Wal-Mart. (My own view is encapsulated in the accompanying graphic.

Any corporation which relies on taxpayer-funded programs to provide medical care for its

employees while it makes billions in profits does not win any "good corporate citizen" awards

in my book. Let's call it what it is: a corporate leech on the body of the Republic/corporate

welfare recipient. If "always low prices" saddles we the taxpayers which billions in

additional expenses which competitors such as Costco somehow manage to pay themselves,

then are those "low prices" truly low or merely subsidized?

For a look into the inner workings of Wal-Mart, let's turn to our first-person account:

Approximately a year ago I was contacted about being the CFO for

Wal-Mart's real estate company. Just the annual capital budget ran approximately $6 billion.

It also had a large staff--approximately 150 people. Anyway after several telephone

interviews Wal-Mart asked me to fly out and meet them.

I ended up taking a flight out of a west coast airport that got me into Northern Arkansas

airport at something like 10:00. Let me tell you it is dark in Northern Arkansas at 10:00

P.M. and I got lost driving to Bentonville. Now this is kind of funny since I have lived

on four continents and travel the world with a map and hardly ever get lost. I currently

fly all over the country to some of its major cities and never get lost, but it was so

dark and the road signs if they existed at all were so small I could not see them. Anyway,

to make a long story short I get to my room at approximately 1:00 am.

It is a $50 room even though there is a Hilton Inn down the road which might cost $20 more

but would be a much better room. There is a lot of noise from pick-ups driving around at

night with modified exhausts (even though I live in a major city I am from a similar area

so I am not an elitist). Anyway I get up at 5:30 am so I am lucky to have 3 hours of sleep.

I drive to Wal-Mart and start the interviews at 8:00 am. These last for 8 hours. Lunch

is a bottle of water and a protein bar which I ate while walking down a hall. I finally

get out and have to drive to the airport. I make it back to the airport and have a raging

headache. I catch a flight somewhere around 7:00 am. I am worn out by the time I get back

to the west coast.

Now this is the kicker. I never ever hear back from them. Not even a “Thanks but no

Thanks” letter and even though they have my email address I don’t even receive a two word

email like "You suck." Nothing!

Now I have my own consulting business and at that time I was very busy. A chargeable day

could bring in a significant sum when I am working on a project like I was at that time.

So in my case time really is money. The HR department had a large number of executive

recruiters and support. What would it have taken to send an email?

In summary, I was very unsure about Wal-Mart. I knew they treated their staff even worse

than most retailers and they have a turnover of close to 50% or more a year. I also do not

support bringing in all of the goods from basically what I look at as slave labor camps

(I am a true believer that if people do not pay employees a decent wage there will soon

not be anyone in this country to buy anything). Finally, I find the quality of the goods

leaving much to desire. Also going from the west coast and NYC where we lived previously

to NM Arkansas would have been a big change.

With that said my mother had cancer surgery a few months before and I would have been

closer to where she now lives. We are both from the South Central part of the United

States and so it was not like we have never been in this culture before. Also, we are

kind of burned out with the West Coast and thought the change would be interesting.

But after never hearing anything from them, all I can think is if this is how you treat

let us say one of the top 30 or so executives in the organization then how do you treat

the bottom level of people who work in your stores. The whole of Wal-Mart is just an

extension of the slave labor environment in China.

To be fair, we have to ask: do Wal-Mart's global competitors, Carrefour (France),

Tesco (U.K.), Bailian Group (China) or Aeon Co and Ito-Yokado (Japan), treat their

executives and employees any better than Wal-Mart? We cannot easily reach an

answer, but we can be appalled by the shoddy treatment offered by Wal-Mart headquarters,

and note that all the go-go hype about China neglects to mention the tens of millions

toiling for less than $100 a month making all the goods which line Wal-Mart store shelves.

The term for this pervasive low wage is the high-falutin' sounding term "global wage

arbitrage." I would call it by a simpler name, exploitation, and

reckon that such distancing terms as global wage arbitrage are masking the brewing of

the next Chinese Revolution as 300 million underpaid, uninsured and pensionless workers

observe the prodigious inequality of their society, i.e. the vast wealth

being accumulated by the 30 million at the top.

As our correspondent observes, perhaps there is a link between Wal-Mart's standards for

its Chinese subcontractors and its U.S. employees: the true cost of "always low prices,

always."

Here are my previous entries on Wal-Mart:

That Price Isn't Cheap, It's Subsidized

The Most Hated Company in America

August 28, 2006

Welcome back, Readers! Today's entry: Stories from the Housing Bubble

Herewith are two stories of the Great Housing Bubble Pop, which we are

witnessing in a weird, slow-motion implosion sort of way. The first story comes from a Comcast

cable installer, who works as a subcontractor for Comcast.

Herewith are two stories of the Great Housing Bubble Pop, which we are

witnessing in a weird, slow-motion implosion sort of way. The first story comes from a Comcast

cable installer, who works as a subcontractor for Comcast.

In the course of a leisurely chat (no, we're not getting cable TV, or DishTV, thank you very much--

recall that I am a poor writer), this hardworking gentleman mentioned that he and his wife

were backing out of the purchase of a 5-bedroom "mansion" (his word) outside of Marysville, CA,

which lies far to the northeast of the San Francisco Bay Area and about 40 miles north of

Sacramento.

They had re-financed their North Bay home and had about $100,000 sitting in the bank, when

a "helpful" relative had convinced him that the money was not doing him any good in a bank

and should be "put to work" in real estate.

The couple already owned a home in the North Bay, and had signed up for the new mansion

when the prices dropped from $450,000 down to $350,000--a recent price reduction which occurred

even before the home was completed. Upon further reflection, however, the subcontractor had

decided to exit the deal before closing escrow for this simple reason: hundreds upon hundreds

of nearly identical "mansions" are sitting for sale, or are under construction in the vast

"desolate" (again, his word) plains surrounding Sacramento. This fellow (working six days a

week by his account, and since it was Sunday, I had no reason to doubt him) had grasped the

nettle, i.e. that such an astounding oversupply could only engender further price drops.

His realtor, rather unsurprisingly, had suggested closing on the house and renting it out.

But our man had enough moxie to know that rents--based on the lower wages--in such a distant exurb

would be far below his carrying costs. His wife had cautioned him that she wouldn't rent to

families with children, at which point the gentleman observed 1) this was discrimination

(another sign this guy knew the realities of landlording/renting) and 2) "who else but

a family with children would rent a 5-bedroom house?"

To top it off, our source had been informed in a sort of legalese aside that he would be

saddled with a $200/month payment for levee improvements on a nearby

river. Upon being re-assured by the salesperson that "there hasn't been a flood in 100 years,"

our source replied, "Then it's about time, isn't it?" When I wondered aloud who had built

these levees, he replied, "Exactly. I'm not doing a Katrina."

This gentlemen had also pondered their initial reason for buying the house--as their retirement

dream home--and concluded that the lack of nearby amenities and amusements (i.e. the

subdivision was plopped in the middle of nowhere) that he and his wife would be reduced to

sitting in this giant house with nothing to do but get on each others' nerves. Now here is a

wise man!

Our source concluded by noting that he'd told his wife that the purchase of this second

home could end up costing them both of their homes. I did not think it proper to inquire

if he would lose his earnest money deposit, but regardless of that

loss (if any), he had clearly reached the right and proper conclusion--closing on the

second-home "mansion" would be a financial catastrophe.

Our second story comes from a friend who moved from the dot-bomb wreckage of Silicon Valley

in 2001 to the warmer climes of Florida. He and his wife had purchased a recently built

home in an upscale coastal community for about $340,000. On a recent visit to California

to explore moving back (public schools were inferior, even in his community,

the private school his son was attending in Florida was hideously expensive, job opportunities

were thin, etc.), he mentioned that they'd pulled out $150,000 in equity over the past

five years, and that the money was gone--family medical expenses, replacement vehicle,

private school, etc.).

A quick search on zillow.com revealed that his house was valued at about $600,000--based, of

course, on recent bubblicious sales--but he reckoned $550,000 was a more accurate number.

(Zillow fiends, beware.) With the $150,000 re-fi equity extraction, his mortgage was now

around $450,000 (they'd only put 10% down). Our friend claimed the eastern seaboard had been

largely unaffected by the big price declines hitting Florida real estate (a claim I can

neither confirm nor deny), but if the value of his house were to decline to $500,000, it

seemed that he was, after paying a 6% commission and closing costs, rather dangerously near

the value of his mortgage. In other words, a sale of his home in the $500,000 range

would net him perhaps his original 10% down payment of $34,000.

Here we have two common threads: massive equity withdrawals which have either been spent

or "invested" in risky real estate wheeling-and-dealing, and would-be landlords realizing that

local rents cannot pay their carrying costs. Neither homeowner mentioned the elephant

in the room: with prices in decline, equity extraction is a thing of the past. A lifestyle

which absorbed $150,000 over five years in "free money" (the equity extracted and spent)

will now have to downsize to mere income.

Multiply this by millions of homeowners, and then ask: what will happen to the

"healthy" U.S. economy when people can no longer freely borrow and spend huge amounts of equity?

As a lagniappe, we have the looming issue of inadequate levees, not just in the Gulf

states but in California. The "hasn't been a flood in 100 years" salesperson is either

ignorant or confused; there have been many instances of flooding in the Sacramento River

basin, up to and including collapsing levees. It is well-known in Sacramento that thousands

of recently constructed homes sit in flood plains. As to whether the new owners are aware

of the flooding risks--they sure give you a lot of forms to sign in escrow, don't they?

August 19, 2006

Will The Market Rally in Fall?

and... A Brief Vacation Hiatus

Astute correspondent S.B. recently posed a most interesting question:

Buying the S&P500 in the fall of a mid-term presidential election year,

and holding for one year, has given returns of 20 to 50%. I don't think

there are any exceptions, and this has worked since the 1930's.

But with the housing slowdown and consumer spending really slowing, how

can the stock market rally? Can it rally in the face of declining

earnings?

Will this year be different? Will the mid-year election cycle rally fail

to occur?

Maybe an interesting topic to cover....

To help answer this excellent and timely question, I asked knowledgeable correspondent

H.I. if he could shed some light on the matter. He sent the following comment and two

charts which display the market positions of professional traders (who are decidely short/negative

the market) and retail traders (us amateur types) who are decidedly long/positive the market:

For your consideration: two charts. This

document is in PDF format and requires Adobe Reader (free from adobe.com)

For a deeper analysis of the market from a technical analysis/historical perspective, H.I.

suggested

Return of The Bear

by technical analyst and author Martin J. Pring. This is a 27-page overview with a great number

of charts. I highly recommend it to anyone who wants some long-term insight into the current stock market.

My own rough-and-ready view is this: nothing goes down in a straight line. The four-year

cycle (discussed here before) suggests there will be a sharp decline/bottom in October 2006.

It would be in the nature of the market to bounce from that low sometime in the

November - January 2007 timeframe. But as to whether that bounce will last... I think S.B.

has hit the nail on the head. With consumer spending questionable, and corporate profits

heading for decline after years of stupendous gains, what could sustainably power the market

higher? Lacking an answer to that, it seems improbable that the market can manage more than

a bounce after the coming October low. But we shall see....

Vacation Hiatus

While some hardy bloggers manage to post during their vacations, I am not one of them,

so my next entry will post on August 28. In the meantime, I offer up several sources

of entertainment/amusement/ideas:

1. an extensive archive of previous entries on a very wide

range of subjects (organized into 21 categories--you're sure to find something of passing interest)

2. a list of recommended books/films

(organized into 11 subjects plus films)

3. an archive of published articles

on a range of topics

4. the nearly-impossible-to-solve-but-fun-anyway I-State Lines contest (In part II, an interest in cryptology puzzles

will be helpful)

5. a variety of stories: Claire's Great Adventure (for teens),

The Adventures of Daz and Alex:

Stories of America (the characters in my novel

I-State Lines),

and forbidden stories (as

they say in the movies, some of which "depict adult themes and settings")

6. my novel

I-State Lines ($20 from the

The Kaleidoscope indie bookstore, shipping free, or $13 from

Amazon.com shipping free for orders over $25--i.e., buy a copy for yourself and one as a gift for a

young adult on your list)

shipping free for orders over $25--i.e., buy a copy for yourself and one as a gift for a

young adult on your list)

If you like my writing here, you'll probably like my writing in the novel, too. If you don't

typically read fiction, then just tell yourself it's non-fiction; it is a road/travel novel,

so that's not much of a stretch. And if you read three chapters every night (they're short),

then you'll be done by the time I get back to posting new material here. What could be more

perfect than that?

In the meantime, thank you for your readership, and I hope you won't forget this little corner of

the Web in my brief absence.

August 18, 2006

The Future of Real Estate Investment Management

Looking into my cracked crystal ball, I caught a glimpse of a certain Joe E. Blow,

Real Estate Investment Management, and was able to discern how his marketing campaign changed in

the future. I might have missed a few details in the blurry fog within the crystal,

but this is what I saw:

Looking into my cracked crystal ball, I caught a glimpse of a certain Joe E. Blow,

Real Estate Investment Management, and was able to discern how his marketing campaign changed in

the future. I might have missed a few details in the blurry fog within the crystal,

but this is what I saw:

May 2005:

Joseph E. Blow

Real Estate Investment Management

I can help you locate, finance and trade properties in all 50 states:

Second homes

Oceanview investment properties

farmland and forestry investment opportunities

preconstruction investing

No documentation adjustable-rate loans

May 2006:

Joseph E. Blow

Real Estate Investment Management

I can help you sell properties in all 50 states:

Second homes

Oceanview investment properties

farmland and forestry parcels

first-rate staging services

re-finance ARMs to fixed-rate loans

May 2007:

Joseph E. Blow

Real Estate Foreclosure Management

I can help you exit problem properties in all 50 states:

negotiated foreclosures

bankruptcy attorney referrals

tax liability management

online auctions (in yuan, yen and euros)

depression/loss/financial counseling

May 2008:

Joseph E. Blow

Real Estate Management

I can help you care for your property:

yardwork

maintenance and repair

pet care/dog walking

eBay sales of your remaining valuables

garage sales are my specialty

solar panel installation

May 2009:

Joseph E. Blow

Services and Sales

Your source for service!

full line of energy conservation products

solar panel installation

vacation pet care

yard maintenance/water conservation

wheatgrass/interior gardening

custom quilting/re-caning service

Isn't it great how Joe transformed himself from an entirely non-productive citizen in 2005,

producing nothing of value, into a productive entrepreneur providing an array of services

by 2009?

August 17, 2006

House of Flying Cliches

There's nothing more lethal in movieland than a razor-sharp flying cliche, and

House of Flying Daggers

There's nothing more lethal in movieland than a razor-sharp flying cliche, and

House of Flying Daggers has nearly as many cliches as it does daggers.

has nearly as many cliches as it does daggers.

OK, so this film is fantasy, through and through. Every dagger finds its mark, every arrow

hits dead-on (unless it's a ruse, in which case it magically only sticks in clothing--now

there's a magic arrow for ya!) But even fantasy films have to present a semi-realistic

emotional world if they are to engage the audience. "Flying Daggers" fails miserably to do so.

We are introduced to a beautiful blind courtesan--who happens to be a wonderful dancer.

Woah, amazing how someone who can't see could do all that and not run into something.

Do ya reckon anyone might want to try a simple test to see if she's really blind, like

throw a fake punch and see if she blinks? Nah.

Then the beautiful dancer waits for a troop of heavily armed soldiers to show up before

announcing her hatred of authority--nice timing, girl! And then she reveals her stunning

martial arts ability--dang, never woulda guessed it!

But here's the real hack. This gorgeous young thing--Zhang Ziyi--who can kick serious butt

at the drop of, well, just about anything, struggles futilely while nearly being raped by

not one but both of her paramours (at different points in the story, of course), and has

to be ignominously saved by someone. And then

instead of slipping a dagger in the gullet of her rapacious suitor, she plays coy! This

isn't just fantasy, it's sick fantasy. Go ahead and try to force yourself on a beautiful

blind girl, because she's suddenly helpless against your lust--and she'll still be goo-goo

eyed for you after. Gag!

But wait--wasn't she in a brothel? So what? Brothels don't condone rape; you pay your

money and accept the service rendered. You don't start ripping the clothing off the joint's

prize dancer unless you want one of your kidneys skewered. There is simply no excuse for

this guy's rapine ways, and no dramatic purpose, either. Yes, Zhang is beautiful, but forcing

oneself on a dancer is not a sign of desire, it's violence pure and simple, fantasy or no

fantasy.

And never mind what she doing in a brothel to begin with--pesky plot lines

are just jumbled together more or less randomly, with no explanation given. She's supposedly

seeking to revenge her father (martial arts film cliche Number 1), but how she planned to

do so from the interior of a fabulous brothel (more like a palace--talk about fantasy!)

is unexplained. The setting appears to have more to do with a teenage boy turned

screenwriter's fantasies about Zhang than a coherent plot

As if this wasn't bad enough, then we get a hoary "tragic" ending: the girl ends up

getting killed while the two rivals for her affections both survive. Now this is realistic,

right, because in real life the jilted guy always kills his lover, not his rival, right?

Right! But do we have to glorify that personification of pathetic male ego run amok? I

was hoping both of the loser guys would adios each other and leave Zhang alone to find

a decent guy. But no, she gets killed off and the two sleazebags survive to nurse their

broken hearts. Gag!

The final fight sequence is so laughable that I could barely finish watching it. Let's see:

two guys are swinging heavy swords at each other, plus kicking and punching and rolling around

grunting, and they start in Fall (cue the dappled leaves on the trees) and continue into

Winter (cue the snowfall). Meanwhile, the woman they each supposedly love (or love enough

to force themselves on--now that's love!) lies near death nearby, ignored.

Uh, have you ever been in a real fight, or even seen one? In the famous real-life showdown

between Bruce Lee and his martial arts master challenger--not the movie showdown, the real one which

occured in the late 60s--Bruce supposedly bested his opponent but found himself exhausted after

only 3 minutes of battle. A few minutes of real fighting exhausted one of the greatest

martial arts practitioners in the world! (This experience prompted Lee to increase his

conditioning.) And yet in the movie, these guys are still going at it for hours,

if not days! Even if you allow this as fantasy, what about them leaving the woman they

both love to die while they duke it out? That has zero emotional realism, and yet their

rivalry for her is the heart of the entire story.

This movie has no emotional center. The love story here is too unbelievable and cliched to

even hold up as fantasy. The "love" we're shown here--the kind in which "passion" drives the

guys to force themselves on the object of their desire--is hardly the sort of "affection"

which a girl will respond to positively, especially one who possesses supreme martial arts abilities.

And if she's so good, how could she fall for the old "two daggers in one" trick her

jilted lover pulls on her? Isn't it rather inconvenient to be invulnerable except when

your disappointed lover is trying to kill you?

Bah, humbug. This movie is wretched. Yes, it's pretty, and so is Zhang, but if you want to

see her in a truly fine film, then go rent

The Road Home.

It's hard to believe that

director Yimou Zhang, who made The Road Home, Ju Dou, To Live, etc. (his films with

Gong Li) has sunk to spinning out tripe like House of Flying Daggers and Hero, both

nonsensical movies with plenty of gorgeously choreographed fight sequences

but no coherent plot or emotional heart.

It's hard to believe that

director Yimou Zhang, who made The Road Home, Ju Dou, To Live, etc. (his films with

Gong Li) has sunk to spinning out tripe like House of Flying Daggers and Hero, both

nonsensical movies with plenty of gorgeously choreographed fight sequences

but no coherent plot or emotional heart.

But they have made money, lots of it, and so that's the kind of film that he now makes.

For a look at his better work (much better), check out

The Road Home.

August 16, 2006

The Party Is Most Certainly Over

The boom is over, the cliche goes, when cabbies and clerks are trading investment tips.

Exhibit 1 in the "boom is over" file: a full page ad in the San Francisco Chronicle

announcing "Learn to PROFIT from the upcoming Real Estate Shakeup" in huge, bold typeface.

Aren't we all interested in profiting from the coming real estate shakeup? Of course!

(Hmm, notice how it doesn't say "real estate decline"?) Free

and easy money is our right! And if you missed the great 10-year real estate boom, never

fear--there are opportunities galore for vast, labor-free profits. According to the ad,

they include:

Foreclosures: now is the time to buy

Stocks: double your income with just a $1,000 investment (who's giving this seminar?

Hilary Rodham Clinton of "how to turn a thousand bucks into $100,000" fame?)

Think rich: get a Millionaire mindset (ah, so that's the secret! Dang, who'd a thunk it?)

Preconstruction real estate: turn $3,000 into $80,000 in six months

Loans: insider secrets of millionaire investors on how to get money

And just in case all these fortunes simply don't appeal to you, then there's

some extra-special bonus get-rich-quick schemes:

Vending machines: start your own home-based business for under $850

Buying and selling oil, gold, silver and sugar

Before we pillage these astonishing profit-making ideas, herewith is my own incredibly

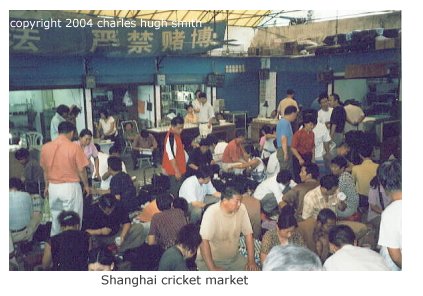

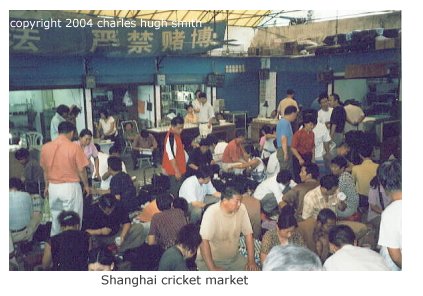

profitable investment idea: crickets.

In China, where space and cash are at a premium, many people prefer a nice cricket for a pet

over a costly dog (though dogs are a sign of wealth, so if you can afford one, by all means,

knock yourself out). Crickets are small, don't cost much to feed, and their chirping is

only annoying if it the cricket isn't your pet.

Do you know how quickly and prolifically crickets reproduce? Talk about profit potential!

Wow! And there's a ready market for your product--right in one of the most fabulous and

fascinating cities on the planet, Shanghai. Now don't get me wrong--I am not mocking the

cricket market. I think crickets make very benign and interesting pets, and I recommend you

look into it as a hobby. The little bamboo cages are quite charming, and there are no vet bills

or weird, deadly diseases spread by crickets.

But let's get back to our "boom is over" ad. I am torn between the vending machine biz

which takes only $850, and doubling my income with a $1,000 in stocks. Both sound good.

But lets' face it, the hands-down obvious way to go is plunking down $3,000 in preconstruction

real estate--like, for instance, signing an option to buy a ritzy condo or house before it's

even built--and then flipping that condo or house into $80,000 in only six months. Yow-zah!

That's what I want to do!

I wonder if the enthusiastic seminar includes a look at the real estate markets which are currently

flooded with condos being flipped by these same preconstruction geniuses. I suspect not.

What I really like about this event is the "kitchen sink" approach. You can make a fortune

in flipping condos, running vending machines, trading stocks, even sugar--you name it!

This reveals a sordid, not quite shocking truth: that we're on the edge of a collapse not

just in real estate but in the entire portfolio of get-rich-quick investments:

stocks, commodities, borrowing like millionaires, thinking like millionaires, making money

off vending machines like millionaires, etc.

I'm thinking of offering a new seminar: Think Like a Thousandaire (formerly a millionaire,

but his paper profits blew away and now he has to actually produce something for a living).

But let's face it, there's no pizzazz in producing goods or services, and so it will never

catch on.

"When men and women are rewarded for greed, greed becomes a corrupting motivator."

John Perkins,

Confessions of an Economic Hit Man

August 15, 2006

Benefits and Inflation: the Untold Story

Read this

release from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, take a look at the numbers

in this chart from the BLS report and then tell me there's no inflationary pressure in

the U.S. economy:

Total compensation costs for civilian workers increased 0.9 percent from March to

June 2006, seasonally adjusted, following a more modest 0.6 percent gain from December 2005

to March 2006, the Bureau of Labor Statistics of the U.S. Department of Labor reported today.

Benefit costs between March and June rose 0.8 percent, greater than the gain of 0.5 percent

from the previous quarter.

Private sector benefit costs rose

0.7 percent for the June quarter, following a 0.4 percent gain in the previous quarter.

Benefit costs for state and local government workers increased 1.5 percent in the June

quarter, following a more modest gain of 0.7 percent in March.

| |

June

2001 |

June

2002 |

June

2003 |

June

2004 |

June

2005 |

June

2006 |

| Union workers |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Compensation costs |

3.6 |

4.3 |

4.9 |

5.7 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

| Wages and salaries |

3.7 |

4.2 |

3.0 |

2.8 |

2.4 |

2.5 |

| Benefit costs |

3.3 |

4.8 |

8.1 |

10.9 |

4.1 |

3.8 |

| Nonunion workers |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Compensation costs |

4.0 |

3.8 |

3.2 |

3.7 |

3.1 |

2.8 |

| Wages and salaries |

3.6 |

3.5 |

2.5 |

2.7 |

2.5 |

2.9 |

| Benefit costs |

5.2 |

4.7 |

5.3 |

6.4 |

4.8 |

2.5 |

Are we the only ones noticing that benefit costs are rising at a much higher clip than

overall inflation (3%)? (And by "we" I mean you and me.)

Are we the only ones who look at these numbers and wonder if the standard line that

globalization/offshoring of U.S. jobs (the so-called "wage arbitrage") will keep inflation low/negligible?

If you examine the jobs statistics for the entire U.S. workforce

(courtesy of the Bureau of Labor Statistics), you find that there are only 14 million

manufacturing jobs--the kind supposedly at risk of being offshored--while there are 22

million government jobs--the kind with benefit costs rising at twice the rate of inflation.

Despite all the rhetoric expended on the topic of offshoring--yes, it's a reality--the

number of jobs which cannot be offshored--even in manufacturing--far outweighs those jobs

which can be performed elsewhere. This explains two characteristics of the U.S. economy:

ever-rising healthcare costs and, as a consequence of that, ever-rising benefits costs.

The figures above reveal that the paycheck wages received by workers haven't even kept up

with inflation, even as the total compensation (wages and benefits) costs to the

employers has been rising. Thus, from the employees' point of view, wages are flat to down,

even as labor costs are skyrocketing from the employers' point of view. How is this

possible? The rapid escalation of benefits costs is largely hidden from the employees,

even as it powers inflation and burdens employers.

Here is the causal chain of stagflation: medical and retirement costs are rising

at double the stated rate of inflation, driven by skyrocketing medical costs. Workers

who have actually seen a reduction in their inflation-adjusted paychecks expect/demand

real wage increases, even as businesses and government agencies have seen their total

labor costs climb much faster than inflation. Their only choice: raise prices and taxes

to cover the higher labor costs. As these higher costs seep into the economy as a whole,

inflation continues rising, feeding even more wage demands.

It's important to recall that the majority of the U.S. economy is service-related

(90 million jobs out of 112 million private-sector jobs), and that

labor is the largest expense in the service sector and government (22 million jobs).

The number of jobs which are vulnerable to "global wage arbitrage" is much lower than the

number of jobs vulnerable to wage and benefit increases.

I have long held that the ultimate driver of inflation in the U.S. economy is not just energy

but medical/healthcare expenses, which constitute about 14% of the entire U.S. economy.

As costs in that sector rise far faster than overall inflation, the costs of benefits rises,

adding to inflation even as workers see less money in their (inflation-adjusted) paychecks.

Anyone who claims we are in a deflationary environment due to global wage arbitrage

(i.e. "made in China") should look at these numbers.

I have long held that the ultimate driver of inflation in the U.S. economy is not just energy

but medical/healthcare expenses, which constitute about 14% of the entire U.S. economy.

As costs in that sector rise far faster than overall inflation, the costs of benefits rises,

adding to inflation even as workers see less money in their (inflation-adjusted) paychecks.

Anyone who claims we are in a deflationary environment due to global wage arbitrage

(i.e. "made in China") should look at these numbers.

Lest you think I am exaggerating the inflationary potential of rising compensation, consider this

report from BusinessWeek.

August 14, 2006

A Thank-You to Readers

and

What About All Those Fixed-Rate Mortgages at Low Interest Rates?

Sometime this weekend, this weblog logged its 250,000th visit of 2006. Thank you,

dear reader, for your readership and for your insightful comments and ideas. 250,000 visits

is no great shakes in a world in which a humorous video clip on youtube or Dr. Z over at

Chrysler garners millions of hits, but judging by the many knowledgeable, thought-provoking

emails I receive weekly from you, I would lay claim to having the most intelligent,

high-bandwidth, skeptical, independently minded and creative readers on the Web.

Sometime this weekend, this weblog logged its 250,000th visit of 2006. Thank you,

dear reader, for your readership and for your insightful comments and ideas. 250,000 visits

is no great shakes in a world in which a humorous video clip on youtube or Dr. Z over at

Chrysler garners millions of hits, but judging by the many knowledgeable, thought-provoking

emails I receive weekly from you, I would lay claim to having the most intelligent,

high-bandwidth, skeptical, independently minded and creative readers on the Web.

Though a quarter million visits may be no big deal to a commercial enterprise,

as a poor, dumb unknown writer, I am honored by your readership. When I started this

weblog (not a true blog, mind you, just a hand-coded variant) in May of 2005, my site

received perhaps 2,000 visits a month. Now it receives 15 - 20 times that.

More important than the statistics is you, the reader.

I am humbled by comments such as this one from Reader S.H.:

I just discovered your site a few weeks ago. How cool. I don't know how you write

intelligently on soooo many topics, but hey, you do. I start off each day reading your

entry. I've also learned a great deal from your writings. Keep up the great work.

P.S. I told my wife you'd be a great person to have as a next door neighbor.

I am grateful for S.H.'s readership, and can only say that I will strive to cover topics

worthy of your attention. Which means more or less everything....

Now on to today's topic!

What about all the people who didn't re-finance to the hilt or buy a home with an

adjustable rate mortgage? What about those who secured low-interest fixed-rate mortgages?

The housing bubble's demise will have no effect on them, so what's the big deal?

Good point. At first glance,

it would seem that the millions of homeowners who never re-financed at all, or who did so

only to lower their interest rate with a fixed-rate loan, not pull equity out of their

house, are utterly immune to the debilitating effects of the decline in current

housing values.

But beneath this apparently benign surface lies two forces which will affect

homeowners, even those with fixed-rate mortgages: property taxes and a declining economy.

As you can see from this chart, significant property tax increases are being logged

practically across the board. Those living in states with with "Prop 13" limits (like California)

on how much existing property taxes can rise are protected, but some 35 states have no

such limits on increases. And while I haven't found any statistics on this, it is fair to

assume that waves of new county assessor's appraisals are washing over the land every month,

raising property taxes to recent bubblicious valuations.

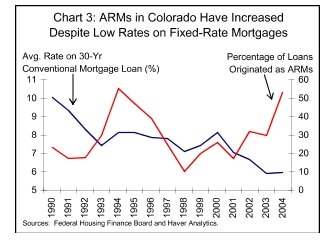

Here is a chart of an economy teetering on the edge of deep recession. Even if tens

of millions of prudent homeowners retained their fixed-rate mortgages and equity, millions

of other more desperate, profligate or deluded homeowners bought or re-financed with

adjustable rate mortgages which are already re-setting at much higher rates.

Here is a chart of an economy teetering on the edge of deep recession. Even if tens

of millions of prudent homeowners retained their fixed-rate mortgages and equity, millions

of other more desperate, profligate or deluded homeowners bought or re-financed with

adjustable rate mortgages which are already re-setting at much higher rates.

Buried within the many flavors of "exotic" loans lie uncounted quagmires. One of our

friends bought a house a few years ago on a fixed-rate (good) interest-only (not good) loan.

When the interest-only period expires in a year or so, then the payment jumps up not just

to start paying the principal, but a little extra to cover all that principal

which accrued during the interest-only "free ride" period. The jump in payments will be

truly staggering to anyone on a tight budget or non-yuppie income.

And as everyone knows, the stalling out or decline of real estate values has effectively

ended the re-finance gravy train. How many homeowners with the desire or need to pull

equity out of their homes have not already done so? And of those with the need, how many

have any equity left to draw out? Judging by the rapid fall-off in re-finance mortgage

applications, not many.

And as everyone knows, the stalling out or decline of real estate values has effectively

ended the re-finance gravy train. How many homeowners with the desire or need to pull

equity out of their homes have not already done so? And of those with the need, how many

have any equity left to draw out? Judging by the rapid fall-off in re-finance mortgage

applications, not many.

Bottom line: as all these millions of interest-only and adjustable-rate mortgages re-set

to much higher payments, millions of homeowners will have less to spend in the great

consumer economy which accounts for 70% of the entire U.S. economy. This means that

virtually everyone with a job or business,

regardless of their secure mortgages, will begin feeling the effects of the bubble's

consequences--the reduction in borrowing and spending which characterizes a recession.

With household debt at record high levels (see chart) and U.S. savings rates at

rather infamously negative levels, there is no other ready source of borrowing or

pool of savings which can fuel further spending.

With household debt at record high levels (see chart) and U.S. savings rates at

rather infamously negative levels, there is no other ready source of borrowing or